1. Fonte Ciane, near Syracuse, just west of the city itself.

To get there, leave town on the road signed for Canciattini. Then fork left onto a narrow lane called Traversa Cozzo Pantano. The Fonte Ciane is at the end of this lane (follow signs to Villa dei Papiri).

The Ciane river meets the sea just south of the city of Syracuse. It is a very short and very narrow river, little more than a brook, winding slowly from its source among papyrus pools and orange groves, in a rather strange landscape of wire fences and barred gates and barking dogs.

I have never seen papyrus growing wild before. In Europe it grows only here, and along another Sicilian river, the Fiumefreddo. The spring at Fonte Ciane takes the form of a reed-fringed pool beside a stand of tall eucalyptus trees. A wooden walkway takes you out over the water so that you can examine the papyrus plants from close quarters. Their stems are extremely tough and cannot be broken without a knife (but don’t experiment—there are signs warning you not to damage the plants). You can also spend long minutes trying to spot the frogs. They make a great din, croaking and puffing out their cheek sacs, but as soon as they hear you approach they fall silent, and locating them can be frustratingly difficult.

The spring takes its name from the Greek word for azure and also from the story of the nymph Cyane, who attempted to prevent Hades from carrying off Persephone and was changed into a fount of water, condemned to everlasting weeping.

Thanks to Wendy Hennessy for supplying the identity of the lizard (Lacerta viridis). They can grow up to 30cm long, excluding the tail. This one was nothing like that length. Reptile enthusiasts can find out more about the species here: www.reptilia.dk/Krybdyr_vi_holder_nu/Oegler/Lacerta_viridis/lacertaviridis.htm. If anyone can identify the frogs, please send a message to editorial@blueguides.com.

Papyrus plants at Fonte Ciane.

The pool itself.

Two frogs.

A lizard, green when it emerged from the foliage.

The same lizard, paler and greyer after a few moments resting on the wooden handrail.

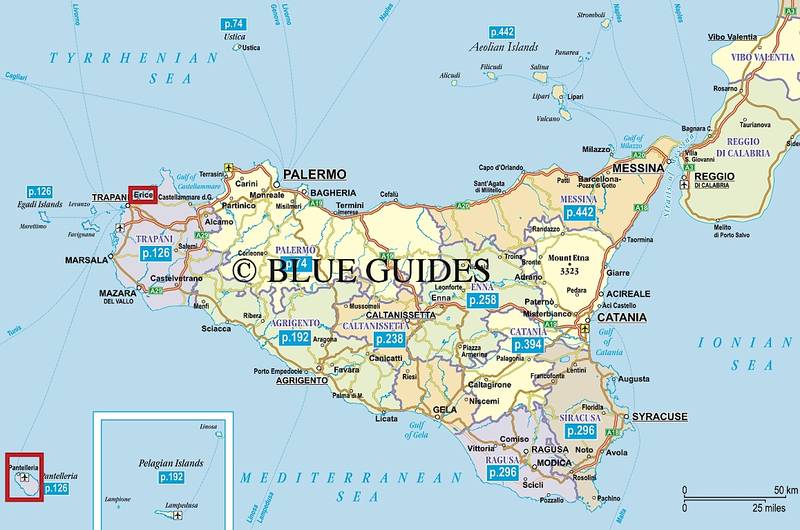

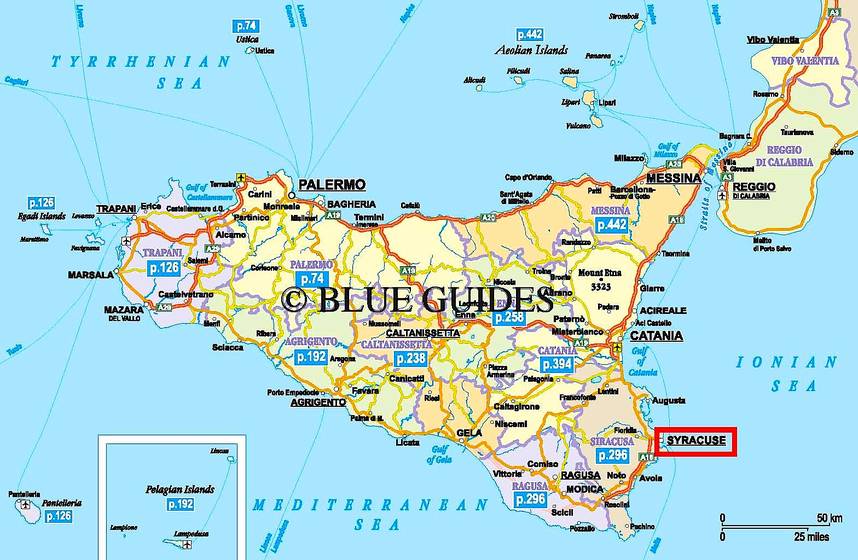

2. Syracuse: where the sun always shines

It was Cicero who said that Syracuse knows no day without sun. Certainly when I have been there I have found nothing to prove him wrong. It is a wonderful place, with many layers of history–you can easily spend a few days here. It was founded in the 8th century BC by settlers from Corinth in mainland Greece and rose to great power under its ruler Dionysius the Elder in the 5th century BC. Under the Romans it was peaceful and prosperous and acquired an amphitheatre. St Paul came here and is said to have preached in its great stone quarries. Syracuse was the birthplace of Archimedes and is now home dedicated to his inventions, appropriately sited in Piazza Archimede (and covered in the new edition of Blue Guide).

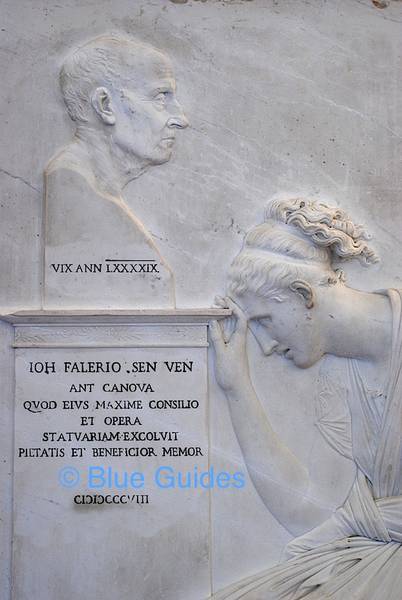

The cathedral (duomo) of Syracuse is one of the most extraordinary sights in Italy: a Doric temple of 14 by 6 columns, built in 480 BC by the ruler Gelon, to celebrate victory over the Carthaginians and dedicated to Athena. The closed by a modern curtain wall and obscured in front by a Baroque façade, that temple’s colonnade is fully discernible today. The interior is one of the most atmospheric I know. The picture here shows a view down the south aisle.

The other picture, an oil-painting, in the chapel at the head of the south aisle, shows Bishop Zosimus with the IHS mongram on his chasuble. It was Zosimus who converted the ruined Temple of Athena into a cathedral. The work is attributed to Antonello da Messina, the great 15th-century Sicilian artist credited with introducing oil painting to Italy.

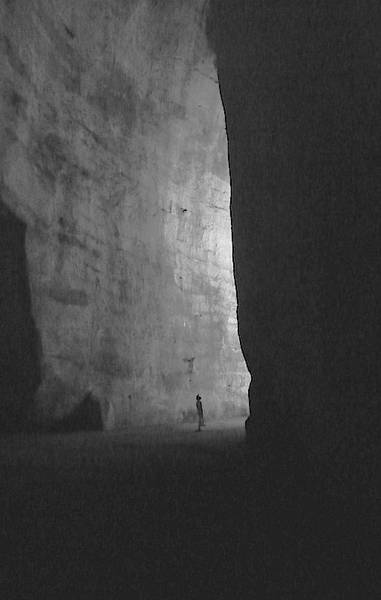

Interior of the cavern, showing its proportions relative to the human figure.

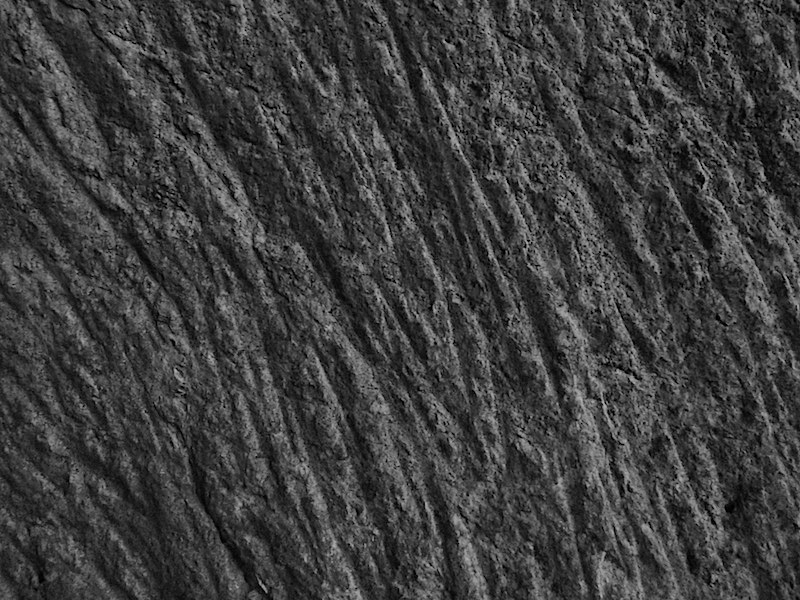

Side wall of the cavern, covered with the scrape-marks of slaves’ chisels.

A famous feature of Syracuse are her ancient stone quarries, known as latomies. These were no ordinary quarries. In ancient times they were also used as internment camps for prisoners and cohorts of slaves were kept here in uncompromising conditions, chipping away at the rock to carve out perfect blocks of exactly one cubit. The best-known of the latomies is the so-called Ear of Dionysius, a tall cave entered by a narrow, man-made slit in the rockface, and extending backwards and backwards into the gloom. Once your eyes have got used to the dim light, you will see that every inch of wall surface is striated with the marks of the slaves’ chisels. The name of the cave was coined by Caravaggio, because of its particular acoustic properties: it amplifies every sound, giving back a single eerie echo.

3. The Temple of Olympian Zeus

To get there, take the Via Elorina. Cross the Anapo river, then the Ciane, and then look out for brown signs taking you left to the Tempio di Giove Olimpico.

Just outside Syracuse to the south stand two forlorn columns, in a field of wild flowers next to a horse farm where sad-looking sway-backed horses canter up and down behind a wire fence. It is a very ancient temple, dating from the 6th century BC, and occupied a strategic spot much beloved of would-be besiegers of the town. As the picture below shows, there is a superb view of Ortigia (the old city) from the temple platform.

4. Pantelleria: the donkeys that were saved from extinction

The island of Pantelleria lies over 100km from Sicily, in fact it is closer to Tunisia. It is famous for its delicious capers and its wines, for having been the island home of the nymph Calypso, with whom Odysseus dallied on his way back to Ithaca, and for having a longish roster of celebrity residents, among them Gérard Depardieu. It is served by boat (seas permitting) from Trapani. What is less well known is that it is also the home of a hardy breed of donkey:Photo: Azienda Regionale Foreste Demaniali, Pietro Alfonso

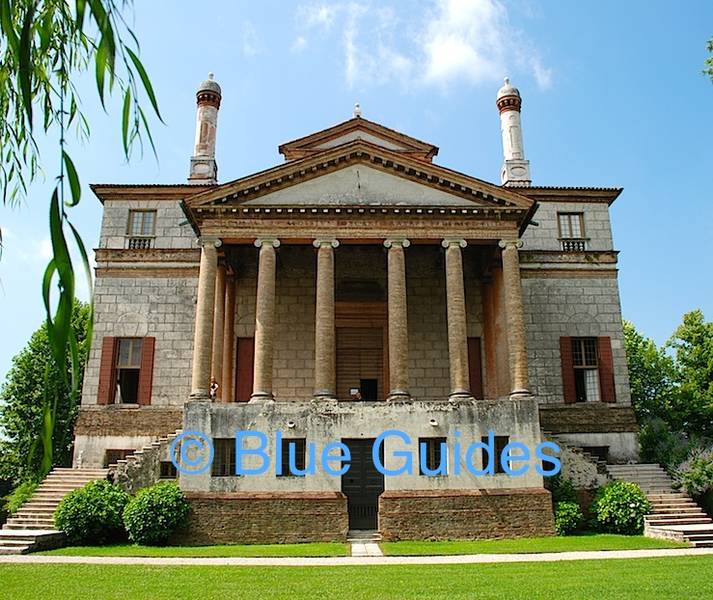

According to Ellen Grady, author of Blue Guide Sicily, the Pantelleria ass is a kind of donkey native to the island, where it has been used since the 1st century BC. It’s very big (the size of a pony), very strong, with a smooth, shiny black pelt. Very fast moving, sure-footed on the mountain tracks. It became extinct 20 years ago because people weren’t using them any more and the last one slipped into the sea and drowned. The exciting news is that the forestry technicians at the San Matteo stud farm at Erice have been able to recreate the donkey, using Jurassic Park-style procedures (taking genes from donkeys throughout Italy which had this particular donkey in their ancestry). It has taken them 17 years, but recently the first four Pantelleria asses were shipped to their island, where they will be used for tourism (trekking around the volcanoes).

The stud farm itself, San Matteo on the Sicilian mainland, is reached from the hilltop town of Erice by taking the Raganzili road. It’s also an agricultural museum. More info (in Italian) on the following website: www.ilportaledelcavallo.it/articolo.asp