“NOLI ME TANGERE”

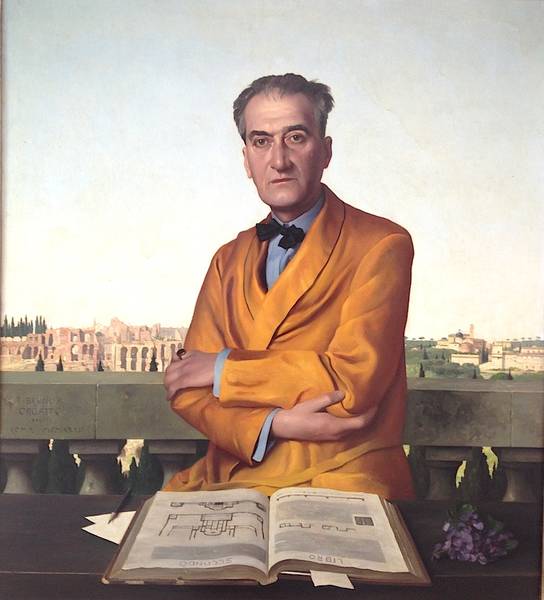

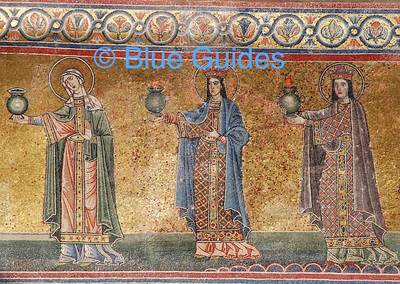

The painter Giovanni Antonio de’ Sacchis (1484–1539) is always known as Il Pordenone, after his birthplace in Friuli, in northeast Italy. According to Vasari, Pordenone taught himself to paint. Certainly his early works are fairly unsophisticated. As he matured, he learned to paint in the Venetian style, with all that that implies in terms of colour and dreamy romanticism. His manner shows a particular closeness to that of Giorgione and Titian. This Noli me Tangere, which hangs in the cathedral museum of Cividale del Friuli, is a good example. It was painted in 1524. Christ appears in a Venetian-pink tunic. Behind Mary Magdalene’s flowing hair we see the angel at the empty tomb. Behind are the alpine peaks that Venetian painters so often included as backdrops in their altarpieces. Christ gestures skywards. We are to imagine him uttering the words put into his mouth by St John: “Touch me not; for I amnot yet ascended to my Father: but go to my brethren, and say unto them, I ascend unto my Father, and your Father; and to my God, and your God” (John 20:17).

When Pordenone left northern Italy in the late 1520s, he fell under the spell of Michelangelo, and his style altered forever, becoming much less spatial, much more sculptural, with highly mannered gesture and with an unsettling, barely suppressed violence. His writhing figures seem to invade the viewer’s space and intimidate him/her. There is something almost Gothic in his dwelling on the more tortured and gruesome aspects of martyrdom. All in all, Pordenone is a fascinating hybrid of Gothic and German elements forced through the Michelangelo mangle.

Important examples of his frescoes and paintings can still be seen in his native town, a pleasant provincial capital with a lively atmosphere and lots of places to eat. Some of Pordenone’s modern buildings are by the Brutalist architect Gino Valle (1923–2003), born in nearby Udine, who worked for many years for Zanussi, producing office and factory buildings for them as well as designs for a number of domestic appliances (including their first washing machine). The Zanussi company was founded in Pordenone in 1916 by the son of a local blacksmith. (It was taken over by Electrolux in the 1980s.)

Pordenone, Udine and Cividale are covered in Blue Guides’ e-guide to Friuli-Venezia Giulia.