At half past seven on an early November morning, the sun is gilding the rooftops but the streets below are still in deep shadow. The newspaper kiosk is doing a slow trade. Few people are about as yet. There are street cleaners, and dog-owners bringing pooches out to empty their bladders, and sandalled nuns and neatly dressed ladies making their way to the church of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte.

It is an old foundation, dating back to the days when this part of Rome was still open countryside. “Delle Fratte” means “of the bushes”. In its present aspect, the church is Baroque, built of warm café-au-lait-coloured brick. Its unfinished tower and tall, slim campanile are the work of Francesco Borromini. The campanile can only really be seen from the street that runs alongside the church, Via Capo le Case, from where, after dusk, the Gabriel audio equipment store projects laser beams onto the church’s lateral flank.

Morning Mass is celebrated in a steady stream, at 7, 7.30, 8 and then every hour until midday. The altar that is in use is not the main one. Instead, the chairs and pews are turned to face a chapel on the north side, with its altare privilegiatum, its “privileged altar” from which, at a time when such things were condoned, you could come away after Mass with a plenary indulgence. This is the “Chapel of the Apparition”, so called because one January day in 1842 the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared in a vision to a young French Jew by the name of Alphonse Ratisbonne, converting him to Christ. St Maximilian Kolbe, the Polish Franciscan who elected to die in place of another in Auschwitz and who is now the patron saint of political prisoners, celebrated his first Mass at this altar in 1918.

A priest clad in penitential purple arrives to officiate. He begins with a prayer for all deceased Minims, members of the Franciscan order of mendicant friars founded by St Francis of Paola in 1435. A chapel dedicated to the founding saint stands on the other side of the church, with an altarpiece by the late-sixteenth-century Renaissance artist Paris Nogari. It was perhaps painted when Pope Sixtus V gave the church to the Order of the Minims. The chapel also contains a scale model of the passenger liner Cristoforo Colombo, dedicated to St Francis of Paola in his guise as patron saint of Italian seafarers.

Members of the small congregation hastily scribble petitions to the Virgin on little slips of paper which they place in a basket on the altar rail. Behind them an aged prelate in voluminous black robes slumbers sprawled in his confessional. As the Mass progresses, he begins to receive clients and is constrained to wake up and shut the doors.

The priest is reading from the New Testament. I recognise the words of the Sermon on the Mount: blessed are the meek, the pure in heart, the peacemakers. In the apse, above the unused high altar, is a fresco of the miracle of the loaves and fishes and below it, in a cartouche, a line in Latin from St John’s Gospel: “Andrew saith unto him, there is a lad here, which hath five barley loaves, and two small fishes.” This is the only reference that I can see to Andrew, the church’s titular saint. To the left, in another chapel on the north side, is Giovanni Battista Maini’s sub-Berniniesque statue of St Anne, depicted lying on her side, her hand clasped to a palpitating stone bosom.

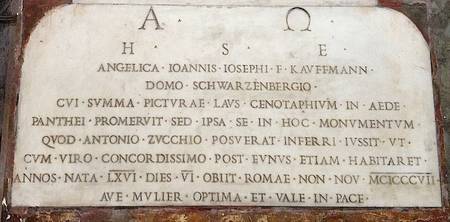

A number of artists from Rome’s foreign community were buried here in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Among them was Angelica Kauffman, known for her portraits and her ceiling and wall paintings. Her plaque is beside the door on the north side, below that of her husband and fellow artist Antonio Zucchi.

Flanking the chancel are the church’s two greatest works of art, Bernini’s angel with the crown of thorns and angel with the titulus, two originals from the series on Ponte Sant’Angelo. I don’t much care for them. I find their facial expressions and exaggeratedly postured limbs absurd. I don’t like their billowing drapery. But they are by Bernini, so I pay them my respects before leaving via the side door into the cloister.

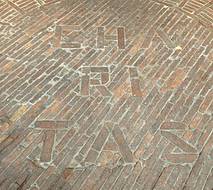

The cloister is a lovely, peaceful space, planted with orange and lemon trees. In the brick pavement the word “Charitas” is picked out, the motto of the Minims, who are enjoined to show brotherly love to one another. Like all Franciscans, they take a vow of poverty. But the Minims of Munich, in order to keep body and soul together, began brewing beer. They named it Paulaner, after the town of Paola, the birthplace of their founder. Hence the beer’s logo of a cowled friar.

Mass is over by the time I go back into the church. Ite, missa est. The congregation shuffles out, shriven, contended, fed with the body of Christ and ready to face the day. A young sacristan from Goa scurries over to the altar to tidy up and another priest in purple arrives to take the next Mass, a tall, handsome young man from Nigeria. A new congregation shuffles in. The process of writing petitions to the Virgin begins all over again. Exaudi orationes servorum tuorum.