A Blue Guides handbook to the wonders of Christian Rome:

“Writing guides to the Christian sites of Rome began in the fourth century. A.B. Barber has now produced the indispensable guide. Packed with practical information, historical details, and charming anecdotes Pilgrim’s Rome will inform, entertain, and inspire.”

Professor Thomas F.X. Noble, President, American Catholic Historical Association

From Amazon:

“I’ve read just about every similarly themed book on Rome I could find, and Blue Guides’ Pilgrims Rome is the best.”

“Blue Guides are the best of the best. I’m not Catholic but I am Christian and wanted a book that gave fantastic Biblical history of Rome. This book is unbiased, detailed, and very easy to read and enjoy. Next purchase Blue Guide Venice and Rome.”

Confraternity of Pilgrims to Rome

Pilgrim routes in Tuscany

20 key history dates

A dictator and handful of emperors

10 top popes

Complete list of popes

Inside look

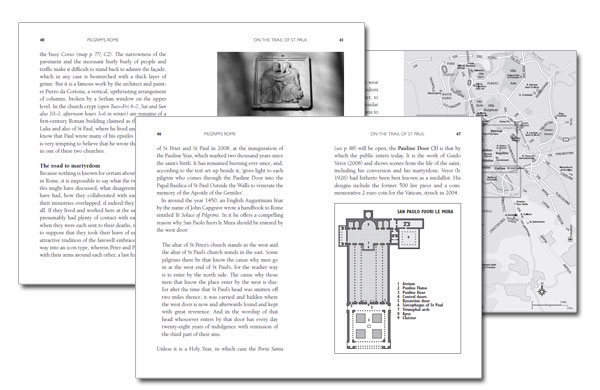

View the full example page – PDF

View the TABLE OF CONTENTS for Pilgrim’s Rome – PDF

View the INDEX of Pilgrim’s Rome – PDF

The St Agnes lambs

“St Agnes’ Eve—Ah, bitter chill it was!

The owl, for all his feathers, was a-cold…”

I have always loved Keats, and he is, of course, a poet with better claims than many others to a Roman association. But as a schoolchild, studying him, I disliked that poem. I sniggered at the line “Into her dream he melted.” I was irritated by the way, for the sake of a perfect jog-trot iambic pentameter, Keats writes “a-cold”, instead of just plain Anglo Saxon “cold”.

It was much later in life that I became acquainted with St Agnes herself, her legend and her beautiful basilica, on the Via Nomentana in Rome’s northeastern outskirts. On the eve of the saint’s feast day, January 21st, the Pope solemnly blesses two white lambs. But why?

The lambs of St Agnes and the pallium

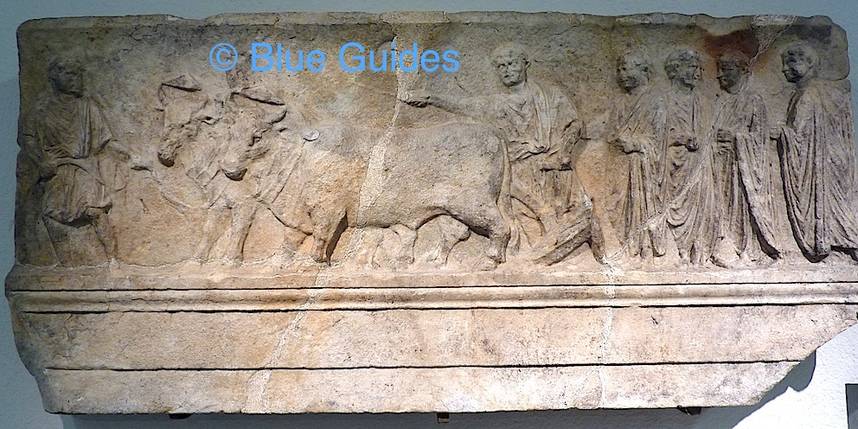

Sigeric of Glastonbury, recently named Archbishop of Canterbury, journeyed to Rome in the year 989 to receive his stole of office, the pallium, from Pope John XV. During his time here, Sigeric visited three churches intimately connected with the manufacture of this vestment, a connection which is still maintained to this day.

Every year, two winter lambs are purchased from the Cistercian monks of Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio at Tre Fontane, south of the city centre (on the site of the martyrdom of St Paul). It is their wool that will be used to make the pallia. On the feast of St Agnes (21st January), the two lambs are taken to the basilica of Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura and solemnly blessed. The association of St Agnes with lambs comes from a play on the virgin martyr’s name (Agnes) and the Latin word for a lamb (agnus). If the pope is not personally present at the service, then the lambs are afterwards taken to the Vatican, decked in white roses, to receive his benediction. After this they are entrusted to the care of the Benedictine sisters of the convent of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, where they are raised with the utmost care until Holy Week, when they are shorn. The nuns weave their wool into the pallia which will be conferred on new metropolitan archbishops on the Feast of St Peter and St Paul (29th June). In the apse mosaic of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, Pope Paschal I is shown wearing the pallium. His is pure white, adorned with two red crosses.

Each of these churches, SS Vincenzo e Anastasio, S. Agnese fuori le Mura with its attached catacomb, and S. Cecilia, is hugly rewarding to visit.

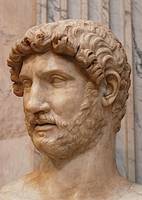

Hadrian, Antinoüs and the Christian Fathers

Hadrian is one of the most interesting and enigmatic of all the pagan emperors. He was a man of contrasts, described in the Historia Augusta as: “in the same person austere and genial, dignified and playful, dilatory and quick to act, niggardly and generous, deceitful and straightforward, cruel and merciful, and always in all things changeable.” He was a very cultured man, interested in art and architecture. Unlike his predecessor Trajan, his interest was not in extending the boundaries of his empire but in consolidating what he had, making sure that its borders held firm. But this does not mean he was inward-looking. The Roman civilisation spread peace through uniformity. All over their empire they built semi-identical cities, each with its temples, its baths, its forum, its theatre and amphitheatre, its circus, its mosaics of Dionysus and the Four Seasons, its public latrines. But Hadrian was not a conformist. He was exceptionally well-travelled and he was interested in the diversity of the peoples he ruled. His own architectural designs flouted the rules; they were almost baroque. In fact, the things that Hadrian admired most lay outside Rome, in Greece and Egypt. At his enormous, sprawling villa near Tivoli he created a little microcosm of his empire, with miniature versions of its beauty spots, from Athens to Thessaly to the Nile Delta to Asia Minor. Some of the statuary recovered from his recreation of the canal which linked Alexandria to the city of Canopus is displayed in the Vatican’s Egyptian Museum.

Hadrian built his Tivoli villa on land that belonged to his wife, the empress Sabina. Their marriage was loveless and childless. Though Hadrian deified his wife after her death, he must have known that she detested him. It is probable that Hadrian was homosexual. The image of his favourite, the beautiful Bithynian youth Antinoüs, haunts the museums of the world like a flitting ghost, portrayed in many a portrait bust or full-length statue, with drooping head, pouting lips and downcast eyes. Antinoüs died in mysterious circumstances, drowned in the Nile in ad 130, at the age of nineteen. Immediately the disconsolate emperor deified him and founded the city of Antinoöpolis on the river’s east bank. Many theories exist about this famous death: few believe that it was an accident. Perhaps the boy was getting beyond the age when it could be seemly for him to belong to Hadrian’s entourage. Or perhaps it was a ritual suicide. The cult of Antinoüs continued well beyond Hadrian’s day. The early Church fathers were in no two minds about it: Tertullian, Origen, St Athanasius and St Jerome are united in their opinion that Antinoüs was merely a man and that his worship was not worship, but idolatry—though they differ in how they express themselves. For St Athanasius, Antinoüs is a lascivious wretch. For Tertullian he is a hapless victim, a person who perhaps had little choice. From this distance, and with our utterly different social outlook, we can have no true idea. The Vatican Egyptian collection exhibits a statue of Antinoüs in the guise of the god of the underworld, Osiris, reborn from the Nile waters. It is a most extraordinary piece, offering a small glimpse into one of the ways in which people have attempted to make sense of death and immortality.

Text © Blue Guides. Pilgrim’s Rome. All rights reserved.

St Chrysogonus and his church in Rome

Not much is known of St Chrysogonus. According to his legend—though it may well be the truth—he was a Roman official beheaded for his faith c.304 in the town of Aquileia, which lies on the Amber Road near the Bay of Trieste. His body was flung into the sea, was retrieved and thence taken to Zadar, from where it was looted by the Venetians in 1202, their first act of ignominy at the outset of the Fourth Crusade. From Venice, the relics made their way to Rome.

The Roman church that bears Chrysogonus’s name and houses the relics stands in the district of Trastevere. Its interior is a pool of tenebrous quiet, sealed off like a thermos flask from the noisy road and tramline outside. Underneath it, accessed from the sacristy and vestry, are the fascinating, suggestive remains of the original Early Christian basilica, dating mainly from the fifth century. Fragments of floor and wall revetment survive. The layout of the apse is clear, along with the frescoed access corridor to the martyr’s former shrine. The best of the surviving wall paintings is in what would once have been the south aisle. St Benedict is depicted healing a leper, whose affliction is indicated by large dark spots.

The remains of St Chrysogonus have been transferred to the upper church, where they are enclosed in the high altar. Above it is a mosaic of the Madonna and Child flanked by St Chrysogonus and St James. It dates from the thirteenth century and is attributed by some to the great Roman master Pietro Cavallini, whose other works in this part of Rome include frescoes at Santa Cecilia and mosaics at Santa Maria in Trastevere.

Lovers’ tokens removed from Milvian Bridge

According to a report in Il Messaggero, the padlocks that encrust the Milvian Bridge like lovers’ barnacles were condemned to revmoval: to be precise, they were taken away on Monday 10th September at 11 am. Officials from the Ministry of Public Works said they lower the tone of the area and were not suited to the historic nature of the bridge, scene of the historic battle between Constantine and Maxentius (which incidentally will celebrate its 1700th anniversary on 28th October). But lovers need not despair. Their padlocks will not be destroyed—even if the love that drove them to fix them to the bridge has died in the meantime. The locks are to be taken to a museum.

A museum?! I, for one, find this a sad decision. Nutty customs such as this are part of what life is all about. I used to love to come to the Milvian Bridge, look at the rusting padlocks with their inscriptions in fading “indelible” marker proclaiming “Together Forever”, meditate on the thrashing of men and horses in the water below as Constantine drove his rival to a watery grave, muse upon the comings and goings of men upon the earth, all that kind of thing…. Eheu!

But all is not lost. Apparently the tradition has now transferred itself to the Trevi Fountain. Find a convenient railing on which to affix your padlock and–flick!–toss the key into the fountain’s frothing waters. Amor vincit.

Or maybe not. Now that the padlocks are down, the city authorities are at a loss where to put them and have solicited suggestions to their Facebook page. “Naturally we will not take into consideration ideas that involve natural beauty spots or sites of artistic interest,” they say. “The removal of the padlocks from the bridge was aimed at curing precisely those ills.”

The column with the sudarium

The famous angels on Ponte Sant’Angelo, by Bernini and his assistants, all hold an instrument of the Passion and bear an accompanying inscription on the plinth. All except for the angel that holds the sudarium, or veil of Veronica, whose inscription is damaged and unreadable. At least, so it had always seemed to me. Grateful thanks to David Lown for pointing out that the inscription IS still there–just–but that most of it was blown away in 1870 by a cannon ball, fired during the struggle for dominion of Rome between papal and Italian forces. Attached is a picture (not very good, but the best I could find, until I go back to Rome again and take another one), demonstrating the mark left by the cannon ball and the remains of the inscription, which once read: “Respice faciem Christi tui” (Look upon the face of thine anointed).

Two fingers on the angel’s right hand are damaged. The angel next to this one, the angel holding the nails, is missing three. The appealingly named Umberto Broccoli, from the Sovrintendenza, has an attractively romantic attitude to the problem of time’s depredations. “One can do all in one’s power to stop the damage happening,” he says, ‘but once it has occurred, there is little to be done. The fragments get lost. One cannot stick them back on. And we can only restore such artworks with original pieces, not with copies. The beauty of these statues cannot be everlasting.” Dust to dust. I like this. Two of the angels are copies already, the once with the Crown of Thorns and the one with the Titulus. The originals are in the little-visited church of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte. Let the others remain.

NB: Thanks to the Mellor family for the image. You can see photos of all the angels on their blog at: rome-wardbound.blogspot.hu/2009/11/ponte-santangelo.html. A series of lovely sepia photos of each angel can be found here: thebournechronicles.wordpress.com/2010/10/28/the-angels-of-ponte-santangelo/

Greet Priscilla and Aquila, my helpers in Christ Jesus…

July 8th is the feast (in the Roman calendar) of Saints Aquila and Priscilla. Very little is known about these two characters, husband and wife and early converts to Christianity. They were friends of St Paul, most likely converted Jews like Paul himself, and—also like Paul—Aquila was by profession a tentmaker. We know that they were with Paul in Ephesus, and that Paul left them there to spread the word, which they did with diligence: “And a certain Jew named Apollos, born at Alexandria, an eloquent man, and mighty in the scriptures, came to Ephesus. This man was instructed in the way of the Lord; and being fervent in the spirit, he spake and taught diligently the things of the Lord, knowing only the baptism of John. And he began to speak boldly in the synagogue: whom when Aquila and Priscilla had heard, they took him unto them, and expounded unto him the way of God more perfectly.” (Acts 18: 24–26). They are two of the earliest missionaries whose names we know.

It is clear that Paul valued them highly. After Ephesus, we find them in Rome. In his letter to the Romans, Paul says: “Greet Priscilla and Aquila my helpers in Christ Jesus: Who have for my life laid down their own necks…Likewise greet the church that is in their house.” It is unknown what heroic deed it was that they performed. It may have had something to do with the commotion raised in Ephesus by Demetrius the silversmith, whose little votive figurines of Diana Paul spoke out so vehemently against. This may also have been the reason why Aquila and Prisca went to Rome.

Their last scriptural appearance comes in Paul’s second letter to Timothy, where the Apostle writes: “Salute Prisca and Aquila”. Since Timothy at the time is thought to have been Bishop of Ephesus, it is probable that Prisca and Aquila had returned home.

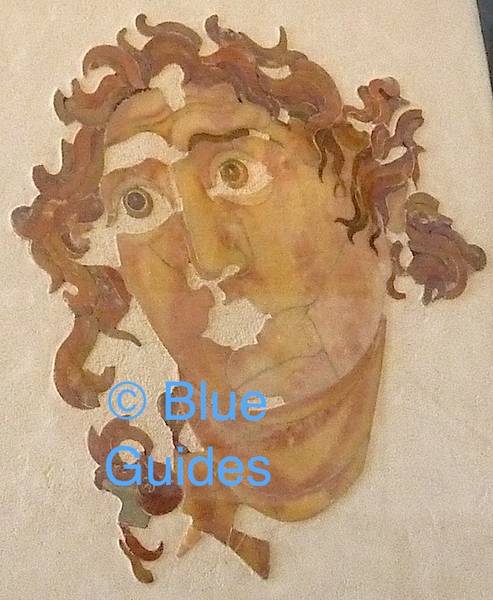

There is a small church on Rome’s leafy Aventine Hill dedicated to Santa Prisca. For some time it was thought to stand on the site of Prisca and Aquila’s house, that very place mentioned by St Paul, where they had received the local Christian community for meetings and worship. The identification is unfortunately no longer accepted. We have no idea where the two lived while they were in the city. Nevertheless, the church merits a visit. It is dignified in its simplicity and underneath it are the remains of a Mithraic temple, dedicated to the cult that rivalled Christianity in popularity until Christianity became the official faith of the empire in the 4th century. (Mithraeum open by appointment on the 2nd and 4th Sundays of the month; T: +39 06 399 67700.) The superb inlaid head of Sol that was found here (pictured left) is on display in the Museo Nazionale Romano in Palazzo Massimo near the Baths of Diocletian (http://bit.ly/ObYu8K).

Earliest-known image of a martyrdom

Under the church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo on the Caelian Hill are the excavations known as the Case Romane (‘Roman houses’; www.caseromane.it). What has been revealed is complex and fascinating and spans at least five centuries. Traces of a wealthy domus with a nymphaeum, a street and shops, an early Christian oratory. Many of the walls still preserve their painted decoration, some of it figurative, some in the form of faux marble cladding. The church takes its name from two mid-fourth-century courtiers of the emperor Constantine II. Under his successor Julian the Apostate, who attempted to reverse the Christianisation of the empire, Giovanni and Paolo were put to death for their faith. The so-called confessio, which is approached up an iron stairway, has a fragmentary fourth-century fresco showing three kneeling figures, apparently blindfolded and awaiting execution. They are identified as Saints Priscus, Priscillian and Benedicta, ‘priest, cleric and pious lady’, who are said to have attempted to locate the remains of Giovanni and Paolo and were arrested and executed, in about 362. According to tradition, they were beheaded. Their feast day in the Roman martyrology is January 4th. This is the earliest-known depiction of a martyrdom in Christian art.

Images of the Crucifixion: closed or open eyes?

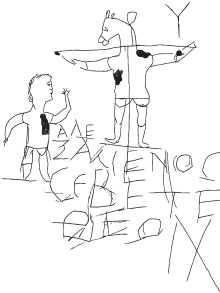

Representations of the crucifixion, in the early days of Christianity, were symbolic rather than literal. A jewelled cross might be shown upon the hill of Golgotha, for example, but the cross did not have Christ fixed upon it. The shame and humiliation of this manner of execution, which the Romans reserved for slaves and traitors, carried a heavy social stigma, and artists shrank from representing the Son of God in such a way. The famous Alexamenos graffito, a second-century scrawl found on the Palatine Hill in Rome and now exhibited there in the Palatine Museum, makes fun of a Christian worshipping his ‘god’, who is depicted as a man with the head of a donkey.

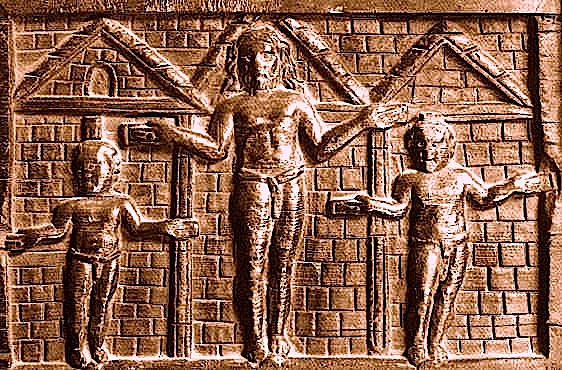

Later, partly in response to the heresy of Arianism, which refused to accept the full divinity of Christ, literal images of the crucifixion began to emerge, with Christ shown triumphant over death: erect, often clad, and with his eyes open. Not a suffering human being, but a victorious divinity. The Volto Santo of Lucca, a cedarwood statuette of a robed Christ, is a famous example of the open-eyed type. According to legend, it was carved by Nicodemus himself. A memorable early 16th-century painting of the Volto Santo, by the eccentric Tuscan artist Piero di Cosimo, hangs in the Szépművészeti Múzeum in Budapest.

Later in the Middle Ages, after Arianism had been outlawed, crucifixion scenes began to concentrate on Christ’s humanity, emphasising his suffering and sacrifice. The former Roman town of Ferento, in Lazio, was destroyed by its powerful neighbour Viterbo in 1172, for harbouring an image of Christ on the cross with open eyes.

In Byzantine art, a different trend is seen. Christ crucified is shown in his agony, eyes closed, with mourners clustered around the cross. But alongside this, in deliberate juxtaposition, is placed a representation of Christ in Majesty. The example illustrated here, from the chapel of the Archangel Michael at Asomatos, Crete (note the soldiers quaintly dressed in 14th-century armour), shows the crucified Jesus with his eyes closed and the risen Jesus with his eyes wide open, emphasising the glorious victory of Christ the Lord after the suffering and death of Christ the man.

The earliest known image of the crucifixion in Western public art is on the wooden door of the basilica of Santa Sabina, on Rome’s Aventine Hill. It dates from around the year 430. Christ’s eyes are open.

The images at the top, from left to right, show: the Alexamenos graffito (2nd century); the crucifixion panel from the west door of Santa Sabina, Rome (5th century); Piero di Cosimo’s Volto Santo (16th century, inspired by an 8th-century statue); wall-painting of the crucifixion from the Chapel of St Michael, Asomatos, with Christ in Majesty above (14th century); detail of the former, showing the closed eyes of the crucified Christ.

A memento of St Peter and St Paul and a superb museum: all under one roof

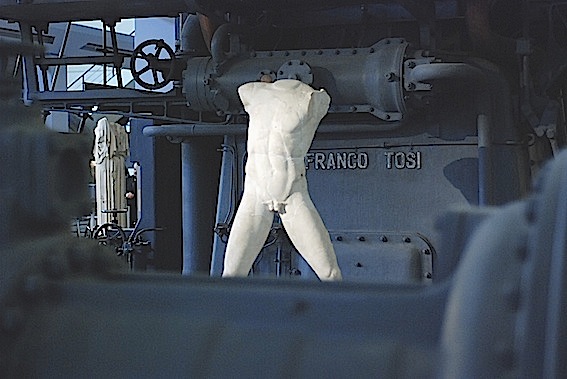

“We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath … a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

These words, from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto, published in 1909, are well known (Tr. James Joll). Marinetti issued a call to arms that was at once forward-looking and narrow-minded; iconoclastic, revolutionary, progressive; but misogynistic, splenetic and tub-thumping; radical but deeply nationalistic; daring and bombastic but intolerant, elitist and hatred-fuelled, intoxicating and at the same time just plain silly. In many ways, it is amazing that we are still talking about him. But then, plenty of things are amazing. Not least the small plot of ground at no 106 Viale Ostiense in Rome.

On the site of the present building there once stood a small chapel, known as the Chapel of the Separation. According to legend it was on this spot that St Peter and St Paul took leave of each other on the eve of their martyrdom. St Paul was taken further southeast, to Tre Fontane; St Paul northwest to the Vatican hill. A little plaque showing the two apostles in a fraternal embrace commemorates this event.

Inside the gates, you find yourself within the precincts of the former Montemartini electrical plant. Now decomissioned, its vast turbine halls, with machinery still intact, are host to an overflow of ancient sculpture from the collections of the Capitoline Museums. Displayed against the beautifully crafted behemoths of the machine age, the chiselled statues and portrait busts from the days of imperial Rome bring Marinetti powerfully to mind. He hated museums.

“We today are founding Futurism,” he boasted, “because we want to deliver Italy from its gangrene of professors, archaeologists, tourist guides and antiquaries. Italy has been too long the great second-hand market. We want to get rid of the innumerable museums which cover it with innumerable cemeteries.”

He was mistaken. There is nothing gangrenous here (most of the statues’ limbs have already been amputated). A museum such as the Centrale Montemartini is nothing like a cemetery. It is a place which conjures the age of marble and the age of cast iron into symbiotic life.