“Within Frames” is the title of an exhibition running at the Hungarian National Gallery until February 18th. It looks at Hungarian art of the 1960s, a decade when state censorship controlled what people could publicly say or think. The English title, “Within Frames”, a literal translation of the Hungarian, does not really sum up what the show is about. “Within the Framework”, or even “Circumscribed” might be nearer the mark. How did artists cope with the restrictions imposed on them? Were they universally obeyed? And if not, how were they subtly subverted?

The exhibition examines a full decade, between 1958 and 1968. The dates are not accidentally chosen: 1958 was the year that saw the introduction of the system of control known as the Three Ts. In 1968, the year of the Prague Spring, art was freed from central control.

Visitors straightaway enter a stalwartly Communist world. The first room is dominated by a mock-up of a prefabricated housing block with its end wall entirely covered in a sgraffito mural: György Kádár’s Family (1958). Kádár was an artist who had received criticism from the authorities for showing symptoms of too much modernity. In this mural he perfectly hones his style, staying within the lines in a way that cannot be footfaulted. A sturdy mother is seen tossing her small son above her shoulders. In his hands he holds a kite with a beribboned tail. An older child, a daughter, rests on her spade next to her father: they have just planted a young sapling tree. The themes of peaceful coexistence, responsible community life, hard work and hope for the future are all expressed—partly literally—in spades.

The enormous power distance between the cult personalities of the Communist ruling apparatus and their smiling, happy people is wonderfully illustrated in Ernő Jeges’s May Day in Komló (1953). This early work shows the hardline world of early Communism. The scene is a May Day (Labour Day) celebration in the mining town of Komló. Officials are surrounded by children waving the Red Flag. Behind them rear the tall winding machines of the coal mine. In the distance stretches the town, newly built, spick and span, and toiling up the hill to salute the Party representatives winds a procession of local peasants, dressed in folk garb. The artist had been one of those who won a scholarship to Rome in the late 1920s and who was given ecclesiastical commissions as a result. Here he has reinvented himself as a propagandist par excellence of the Socialist Realist utopia.

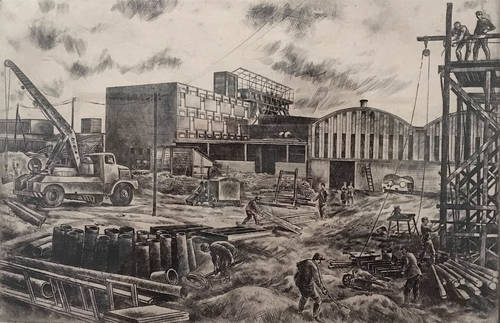

Five years later, the situation was somewhat relaxed. Art was given more freedom to move but it still had to operate within the strictures of the Three Ts. The Ts are the initial letters of the Hungarian words for Subsidised, Tolerated and Banned, the three categories into which art was corralled. Anything that extolled Western consumerism, that reflected negatively on the Soviet crushing of the 1956 revolution, that criticised the Party, that mentioned the post-WWI Treaty of Trianon (which had given large swathes of Hungary’s former territory to her Comecon allies), was taboo. Banned art, according to a Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party decree of 1965, was art that showed “not the reality of society but which holds up a distorted mirror to reflect the artist’s own irresponsibility and pessimism.” Gyula Marosán, with works like The Secret Police is Checking the Border Again or The First Fallen Freedom Fighter (illustrated here) was clearly in the banned category.

With such strict rules to follow, one might expect most of the art in this show to be crude and provincial. It isn’t. Early on it becomes clear how much Hungarian left-wing artists had in common with their Western counterparts. Picasso’s Dove of Peace (examples on show) and Renato Guttuso’s Land-grab in Sicily clearly demonstrate that artists across the continent were concerned with the threat of nuclear war and with social questions. And an area where Hungary was not isolated at all was furniture design, as attested by many of the beautiful objects also included in this show. Particularly fine is a cane-seated chair by Zsuzsa Kovács, with delicately tapering legs. Kovács was a pioneer designer, a committed socialist, and an early advocate of the fitted kitchen. Her avowed aim was to help alleviate the domestic burden on the working woman.

Another thing emerges from this show. That operating within strictly defined boundaries does not necessarily place a stumbling block in the way of creativity. One only has to think of wordy poets confined to the fourteen lines of a sonnet and thereby producing some of their finest lyrics. Many artists in this decade, even those who were not necessarily fellow travellers, found a direction from which they never deviated, even after state control was relaxed. The Conservative Realist painters (acceptable theme: society as it is) or artists of the Great Plain School (acceptable theme: peasants and agriculture) are good examples.

For the honest portrait that it gives, this is a superb show. The artworks have extraordinary documentary value and interest. Often, when sifting through a lifetime of old photo albums, all the carefully contrived arty shots that seemed so marvellous at the time, seem completely pointless. Why on earth didn’t we take more everyday snaps of the family sitting around the kitchen table? It says much more about who we really are.

Reviewed by Annabel Barber. Blue Guide Budapest will be published in the spring.