Augustus, ‘the revered one’, was the honorific title of Gaius Octavius, great-nephew of Julius Caesar and one of the most remarkable figures in Roman history. He has given his name to the month of August.

Having no legitimate heir of his own, Julius Caesar formally adopted Octavius, and he exploited this position ruthlessly when the Republic collapsed after Caesar’s assassination. His uneasy co-operation with Mark Antony soon turned to open conflict. Mark Antony had taken command of the eastern portion of the empire, and when he allowed himself to become entangled with Cleopatra, Augustus seized his chance to brand them both as enemies of Rome. In 31 bc their navy was routed at the Battle of Actium and both committed suicide.

Back in Rome, with wealth and success to his name, Augustus could easily have become a dictator. However, that was not his way. Despite the ruthlessness of his youth, he now showed himself to be measured and balanced. His favourite god Apollo was, after all, the god of reason. Knowing that the senate was desperate for peace, he disbanded his army and the senate in turn acquiesced in his growing influence. The title Augustus was awarded him in 27 bc and he gradually absorbed other ancient republican titles too, as if the old political system were still intact. Behind this façade he was spending his booty fast. He claimed to have restored no fewer than 82 temples in Rome. He completed the Forum of Caesar and then embarked on a massive one of his own, centred on a temple to Mars Ultor: Mars as the avenger of his adoptive father’s murder.

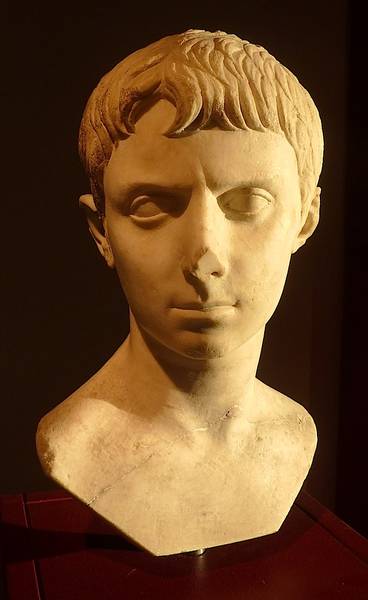

Augustus was keenly aware of the power of his own image. Not only was his temple adorned with a great bronze of himself in a four-horse chariot, but other statues, playing on ancient traditions, were distributed throughout the empire. Augustus appears in one of a number of stock guises: as military commander, veiled and pious priest, or youthful hero, as in the example shown here, a bust from the northern Italian town of Aquileia, where Augustus received King Herod in 10 bc and reconciled him with his two sons. One estimate puts the total number of statues of Augustus scattered around the realm at between 30,000 and 50,000.

The empire prospered under Augustus’ steady control: there was no challenge to his growing influence and poets such as Virgil and Horace praised his rule. A less lucky writer was Ovid, exiled to the shores of the Black Sea, allegedly for lampooning Augustus’ programme of moral reforms. In 2 bc the great leader was granted the honorary title Pater Patriae, ‘Father of the Fatherland’, an honour which left him deeply moved. He died in ad 14, and it was observed at his cremation that his body had been seen ascending through the smoke towards heaven. The senate forthwith decreed that he should be ranked as a god. By now the Republic had been irrevocably transformed into an empire, and emperors ruled it for the rest of its history.

This text extracted and adapted from Blue Guide Rome and Blue Guide Literary Companion Rome. ©Blue Guides. All rights reserved. For more on the town of Aquileia and its fascinating Roman and early Christian remains, see our e-chapter: Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

And when you visit Aquileia, or before seeing the exhibition in London, read up about the city in the Blue Guide e-chapter: Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

We have just opened am Exhibition of Aquileia The Great Lost City at the Royal Geographical Society in London. It was opened to the public on the 6 March 2015 and entrance is free. Viewing times are 10am-5pm Mon-Friday. 10am-4pm Sats. Closed Sunday. Nearest Underground South Kensington. Aquileia was considered to be the second Rome in the Republican period. It was a beautiful city, cosmopolitan highly cultured and with a population of more than 100,000. It was crucial to the creation of the Roman Empire, its defence and its well being. It is unknown in the Englsih speaking world. Do come along with your family and friends and enjoy the exhibition in the gallery and then visit Aquileia! Peter Marshall