by Alta Macadam

This exhibition, running at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence until 13th July, is the first ever show devoted to this sculptor, who was of supreme importance during his lifetime in 16th-century Florence, not only for his skill as an artist but also because he was the official sculptor of the Medici. He learnt his art directly from Michelangelo and (the far less well-known) Giovanfrancesco Rustici. Bandinelli’s pupils included Vincenzo de’ Rossi, Ammannati, and his successor as court sculptor for the Medici, Giambologna. The Bargello is therefore the most fitting place to hold this exhibition, since in the first room of the museum, recently rearranged, all of these sculptors are very well represented.

The reason for the notable lack of interest in Bandinelli (1493–1560) until now is probably due most of all to the fact that he was clearly an unpleasant man and jealous of his position as the Medici favourite. In public he was particularly fond of doing down Cellini, whom we know far better through his delightful Autobiography and who was by far the greater sculptor, but who suffered from the success of his rival.

Bandinelli had the grossly mistaken idea to carve a colossal statue as a pair to Michelangelo’s David outside the entrance to Palazzo Vecchio. It is one of the worst sculptures produced in Florence in the 16th century. Representing Hercules and Cacus, the two figures are flabby and in fact border on the ridiculous. Cellini was delighted to point this out to Cosimo I in the presence of Bandinelli, but Cosimo still continued to commission statues from Bandinelli rather than Cellini including, nearly thirty years later, the huge but feeble and languid Neptune for the fountain a few metres away in Piazza della Signoria (it had to completed by his pupil Ammannati after his death). Cellini’s famous Perseus is in the loggia of the same square but its model and original base and exquisite bronze statuettes are preserved in the Michelangelo room where the exhibition begins. Cellini would have been satisfied indeed that these and some of his other superb sculptures are displayed here, establishing his pre-eminence.

Bandinelli’s earliest sculptures in the exhibition include a mutilated classical Mercury from the Louvre, a bas-relief of the Flagellation from Orleans (with a plaster cast of it from the Casa Martelli in Florence) and several red chalk drawings from the Louvre and another from the British Museum. There is also a small relief of the Deposition in gilded and painted stucco from the Victoria and Albert Museum. All these demonstrate clearly Bandinelli’s superb skills as a draughtsman, and also particularly as a sculptor in low relief.

A number of busts by him of his patron Cosimo I are displayed together, including one which he carved for the façade of his own residence in Via Ginori, as a proud statement of his allegiance to the Medici family (now in a private collection it has rarely been seen since its was removed from the house front). Accompanying these works is Cellini’s colossal bronze bust of Cosimo, now even more impressive since, in the new display of the permanent collection here it has been raised higher on a pedestal, and clearly it is a greater portrait of the powerful Duke than any produced by Bandinelli.

Some of Bandinelli’s best marble reliefs were carved for an elaborate new choir he designed for the Duomo, directly beneath the dome, but which was never completed and was ultimately considered unsuitable for the church (it included two entirely nude statues of Adam and Eve which were to flank the altar, and which are on permanent display in this room). Some of the superb original reliefs are on display next to a model of how this ambitious project would have looked: it was to have included some 300 similar reliefs. Bandinelli’s Bacchus is also displayed here, rejoining three other statues on permanent display in this room: Sansovino’s earlier Bacchus; Cellini’s classical Ganymede; and Michelangelo’s David-Apollo, all four of which are known to have been special favourites of the Duke’s, which he kept together in a room of his palace.

The exhibition continues in two small rooms also off the courtyard. Here you can see a series of Bandinelli’s exquisite small bronzes, all from the Bargello collection. Seen on their own they confirm his mastery of this genre. All around the walls are examples of Bandinelli’s splendid drawings, many in red chalk, from the Uffizi, including two of his famous patrons Pope Leo X and Cosimo I, clearly drawn from life in the 1540s.

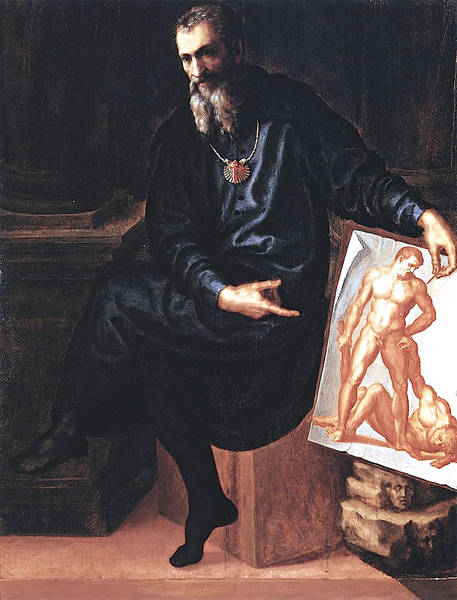

In the last room there is a memorable portrait of the young Bandinelli by an unknown Florentine painter influenced by Andrea del Sarto and a marble relief of a bearded man attributed to Bandinelli, as well as his self-portrait in terracotta dating from around 1557. The show helps reinstates Bandinelli as an artist of great merit, and it is always a delight to return to the Bargello, which is one of the finest museums in Florence and never, for some mysterious reason, over-crowded.

Alta Macadam is the author of Blue Guide Florence.