With the new edition of the Blue Guide to Rome just off to press, it is time to catch up on new books to accompany it. I recently reviewed Richard Bosworth’s excellent Whispering City, Rome and its Histories for this site and now there are two more studies that have received widespread attention. Both are set in Rome at a time when it was ruled directly by the popes, both are the result of meticulous, even inspired, research in the archives and both focus on strong women. Yet what different women they are!

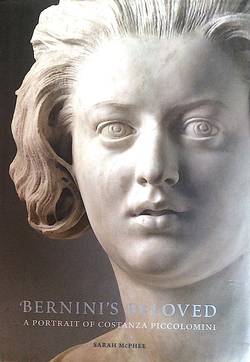

Costanza Piccolomini is perhaps best known as the mistress of Bernini, her face slashed on the orders of the enraged architect when he discovered she was also sleeping with his brother. She is the subject of one of his most striking busts, a wonderful work and explored here from every angle (it is now in the Bargello museum in Florence.) After the rupture with Bernini, Costanza was thought to have vanished from the record, but by assiduously ferreting through archives of every kind, McPhee revives the later life of a courageous and successful woman.

In contrast, there are the manipulations of Maria Luisa, a nun who made herself madre vicaria of the convent of Sant’Ambrogio in Rome (the building was in the Piazza Mattei by the lovely Fontana delle Tartarughe). There is not much to redeem Maria Luisa as she uses her feigned spiritual prestige to seduce her fellow nuns and even to murder those who oppose her. It is only thanks to an opportune misplacing of the once-secret Inquisition files that the scandal can be told at all.

Costanza’s name was a grand one: the Piccolominis had produced popes and duchesses; but the impoverishment of her branch of the family meant that her name was all she had to cling to. She even had to be given a charitable dowry, a grant to keep young girls such as herself from a life on the streets. Yet her husband, Matteo Bonucelli, scultore, was a successful craftsman, a loyal member of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s team at St Peter’s and a restorer of antique sculpture. They married in 1632 when she was eighteen and he ten years older. McPhee uses birds-eye engravings of 17th-century Rome to show where they lived, and as her husband’s career prospered so did their homes. Their house, in today’s Vicolo Scanderbeg, close to the Trevi Fountain, boasted a grand doorway of travertine blocks, loggias overlooking a courtyard and a piano nobile more suggestive of a palace than an artisan’s home. Quite how Costanza managed her varied love life is unknown and one wonders whether Matteo acquiesced in the affair to please his formidable boss. Yet, quite apart from the scar left by the face-slashing, there was more for Costanza to suffer. She was hauled off by the papal police, the sbirri, as a donna dishonesta, and incarcerated in the Domus Pia, a home for ‘wayward’ women. Bernini was, apparently, fined 3,000 scudi, but then absolved by his patron, pope Urban VIII.

It is from the Domus Pia that we get the first evidence of Costanza’s spirit and accomplishments. She managed to compose a petition for her release addressed to the Governatore of Rome. It was written in her own hand—and it worked. She was released back into the care of her husband and they lived together for another fifteen years until his death in 1654 left her a widow at forty. Costanza could then have faded back into obscurity, but her husband’s flourishing business had left her many contacts and she was soon being addressed as Costanza scultora, buying and selling pictures to a clientèle that gathered around the new pope, Alexander VII. Costanza stayed on in the Vicolo Scanderbeg and descriptions show that its galleries and hallways were full of works of art on offer. Among her clients was the Duc de Richelieu, to whom she sold Poussin’s Plague of Ashdod for 1,000 scudi. It is now in the Louvre.

Moreover, she was not alone. A year after her husband’s death, Costanza gave birth to a daughter, Olimpia Caterina Piccolomini. The father is unknown but Costanza was especially close to the Abbé Domenico Salvetti, prefect of the Vatican Archives, and it was he who became guardian of the seven-year-old child when Costanza herself died in 1662. McPhee takes us on further and it is good to report that Olimpia herself flourished. She married twice, although she had no children, and was described as ‘Illustrissima’ at her own death in 1736, when the lengthy legal struggle over her inheritance provides McPhee with even more details of Costanza’s life.

This is a book that overflows with detail on life in Baroque Rome. McPhee takes excursions from the main text to talk about the best way of sewing up a scar (all too often a way of inflicting permanent humiliation) or the methods used to enforce the penitence of women. She discusses and follows through the fate of pictures and sculptures known to have belonged to Matteo and Costanza. Overall she provides a model of how the portrayal of a once-vanished life can be composed from meticulous work in the archives. The illustrations are particularly splendid.

The archives for the Inquisition inquiry into the goings-on in the convent Sant’Ambrogio were not as scattered as those of Costanza’s story but they had vanished as completely. They were found by chance by the German church historian Hubert Wolf in the Stanza Storica, a hall of the Archives of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith in the Vatican. They took up six feet of shelf space but there was no logic to their placing and they did not seem any different from the mass of papers around them. Shelved there by mistake (or perhaps deliberately to conceal them), they showed that what sounded like an anti-clerical fantasy of misbehaving nuns was actually completely true.

The story begins with a German aristocrat, Katharina von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a widow who was accepted into the convent of Sant’Ambrogio in 1858. As a German of noble birth in an Italian community, she would always be an outsider, but within fifteen months she was clamouring to escape for very different reasons. There were secret rituals among the nuns from which she was excluded and she believed she was being poisoned. Luckily she had good connections and her cousin, who was in the circle of Pope Pius IX, managed to get her out and install her at his the estate, the Villa d’Este at Tivoli. Having collected her thoughts, she made a momentous decision: to write up a denunciation of the convent that she presented in person to the Roman Inquisition.

The convent had already had a troubled past. Its founder, Maria Agnese Firrao, had claimed to be a saint, the recipient of visions and miracles. There were many doubters, however, and her ‘false holiness’ had been formally condemned by the Inquisition in 1816. She had been removed to the seclusion of a convent in Gubbio where she had died in 1854. The convent in Rome, however, survived, but Katharina’s first accusation was that the nuns had continued to honour their founder as a saint. In other words they were defying the orders of the Holy Office. This required a full investigation.

The transcripts of the intrusive and persistent interviews that followed gradually reveal the full scale of a far wider scandal. It centred on a beautiful nun, Maria Luisa, who had manipulated herself into the positions of novice mistress as well as vicaress, the deputy to the abbess, by the age of 24. Messages of support from the Virgin Mary were taken on trust by the credulous electors and Maria Luisa went on to use these to encourage sexual intimacy with her novices as a form of initiation. Whenever doubters protested, the direct commands of the Mother of God to Maria Luisa were used to overcome their hesitations. There were even letters from the Virgin Mary, always written in bad French, to back up the vicaress’ demands.

At a time when a reaction against the rationalism of the Enlightenment was leading to a renewed emphasis on the reality of miracles, it was easy for Maria Luisa to attract into her bed the confessor to the convent, the Jesuit Joseph Kleutgen, who ten years before had written a scholarly book on the importance of miracles. All too readily he accepted that she needed special protection of a physical kind that allowed him to disregard the clausura, the sealing off of the nuns, and spend the night in Maria Luisa’s cell.

Then there were the attempts to poison other nuns, not just the German Katharina but those who saw through Maria Luisa and recognised what was going on. There were probably three deaths that could be attributed to her, all involving the symptoms of poisoning. The letters from the Virgin Mary foretold the deaths of nuns who had offended the Mother of God by their sins of pride.

As Maria Luisa’s guilt was revealed and condemned by the interrogators, the Inquisition did everything it could to keep the scandal secret. The supervision of the convent by its confessors had failed completely but this could hardly be admitted. The convent was closed down, ostensibly on the grounds of the misplaced veneration of its foundress. Maria Luisa was sent to a penitential cell and gradually disintegrated into mental breakdown. The confessors who had been so easily deceived by her were reprimanded and virtually nothing but vague rumour remained. The story was forgotten until Wolf’s opportune discovery, and as a result the frankness and scope of the confessions come all the more as a shock.

Although The Nuns of Sant’Ambrogio will be read by many for its salacious details, it tackles fascinating questions of religious experience. The campaign to restore the miraculous into the centre of Catholic life had made it imperative to evaluate the visions that isolated nuns (or, in the case of Lourdes, the young girl Bernadette) claimed to have experienced. In Maria Luisa’s case the stories were fabricated, but all too readily believed, thus allowing her to achieve spiritual power over others. Who dares to challenge the Virgin Mary, especially when she write letters? Even to this day the Church finds it impossible to deal with her many appearances and the impassioned messages of despair over the troubled world that she passes on to favoured members of the faithful.

Wolf does not forget that he is a serious church historian and The Nuns of Sant’Ambrogio is also an analysis of the workings of the Inquisition within the papal government. Once it took on a denunciation, its methods were rigorous but fair and it was persistent questioning that led to the breakdown and confessions of the participants in the scandal. The punishments were mild—after all, Maria Luisa was guilty of three cold-blooded deaths by poisoning—but it was the overall demands of secrecy that conditioned much of the outcome. If there had not been an aristocrat with influential connections at hand, the goings-on might never have been exposed. In the hot-air atmosphere of papal Rome in the 1850s, when power struggles and intrigue permeated the government of the Church and city, who knows what was going on elsewhere? We can only await more lucky finds in the archives.

Sarah McPhee, Bernini’s Beloved, A Portrait of Costanza Piccolomini (Yale University Press, 2012); Hubert Wolf, The Nuns of Sant’ Ambrogio, The True Story of a Convent Scandal, English translation by Ruth Martin (Oxford University Press, 2015). Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides and contributor to the forthcoming new edition of Blue Guide Rome (spring, 2016).

To see more details about this book, check the Amazon links below.