We were off with my group from Florence to Prato, where in the cathedral there is the Chapel of the Girdle of the Virgin Mary—not any old girdle, but the actual one that she dropped down to Thomas as she was being assumed into heaven. It is exposed on its feast days from a pulpit, one of the most beautiful and exhilarating creations of Donatello (the original now under cover in the adjoining cathedral museum). After the delight of seeing it, we still had time to fill in and so on the way back we stopped off at the Villa di Castello, one of the original 16th-century Medici villas, once graced by Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and now the home of the venerable Accademia della Crusca, the guardian of the purity of the Italian language.

The garden is famous for its extraordinary collection of citrus fruits and it is hardly surprising that this was one of the first stops for Helena Attlee in her absorbing story of citrus growing in Italy. The garden was created in the 1540s by Niccolo dei Pericoli, known to this day by his schoolboy nickname, Tribolo, ‘the troublemaker’. He knew what he was up to, making sure that the garden was divided up with walls and lots of shade to provide the perfect temperature for the growing fruit. All this was swept away in the 18th century and the more formal open spaces are now too hot for their produce but the garden still impresses with its hundreds of large terracotta pots and extraordinary array of fruits. They are dragged off in the winter into the garden’s limonaia, the lemon house. Many of these limonaie are spectacular buildings in their own right, especially further north among the lemon growers of Lake Garda, where further protective shelter from the cold is needed.

There were only three original species of the citrus genus in Asia, the mandarin, the pomelo and the citron, but they cross-pollinated so easily that hybrids soon formed and flourished even before any fruits arrived in Italy. The citron was the first to appear, in the 2nd century AD, as a mysterious newcomer in that it is ungainly, virtually inedible but exudes a wonderful perfume that suffuses everything that it touches. Lemons, a hybrid between citrons and sour oranges that are themselves a hybrid between a mandarin and a pomelo, arrived in Sicily with the Arabs in the 9th century while pure mandarins only arrived, from China via Kew Gardens, in the 19th century. By then luck and ingenuity had created the extraordinary mix of citrus fruits that made classification a botanist’s nightmare—especially as aristocrats delighted in creating as many exotic and grotesque specimens as possible.

The distinct climatic niches of Italy and Sicily fostered their own varieties. If you are looking for the best arancie rosse, blood oranges, you must come to the slopes of Mount Etna, for here the difference in temperature between day and night is at least ten degrees, without which the blood-coloured pigments cannot develop. For the treasured oil of the bergamot, a natural cross-pollination between a lemon and a sour orange, a thirty-five kilometre stretch of coastline in Calabria, where cultivation began in the 17th century, provides the finest in the world, while the Ligurian coast is the home of the small and bitter Chinotto, most usually found as an ingredient of Campari, but now enjoying a revival in its own right.

Varieties come and go as easier ways of working or developing the land challenge the original traditions and it is only the most skilful gardeners who can keep ancient specimens alive from one generation to the next. Attlee seeks out these dedicated few, some of whom may indeed sustain revivals of vanished species. The curator of the Castello garden, Paolo Galeotti, had a spectacular coup when he spotted a twig sprouting the celebrated bizzarria, a citrated lemon that had vanished without trace for decades. It is now flourishing. Alas, alone and unprepared as my group were, and without the expertise of Helena Attlee or Signor Galeotti at hand, we missed seeing it (and how could I have taken my recent Turin tour members to the excellent Via del Sale restaurant without insisting on their sorbet made from madarino tardivo di Ciaculli, with a flavour ‘so intense it could be consumed only in tiny mouthfuls’).

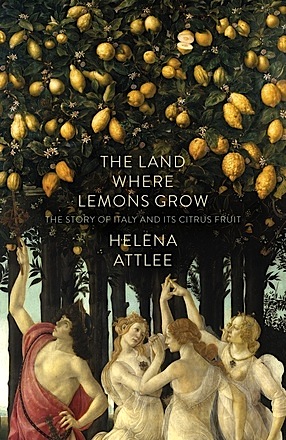

It was Goethe who dreamed of the land where the lemon trees bloom and this delightful and informative book is full of the sun, sensuality and scents of Italy. From now on anyone shopping for standard oranges and lemons in their local supermarket will be consumed with guilt at their lack of discrimination. I am not sure whether our excellent greengrocer will be able to source Limone femminello sfusato amalfitano, the distinctive Amalfi lemon, now given protection from outside competitors by the EU, but I have been promised Tagiolini alle scorzette di arancia e limone for supper and, as the summer warms, we might even try the old lemon-growers’ trick of trapping flies in a concoction of ammonia with an anchovy added to it. But please may we have a new edition with a sumptuous display of coloured prints so that we can feast our eyes on the richness of these wonderful fruits when winter comes to northern Europe?

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides.

The Land where Lemons Grow: The Story of Italy and its Citrus Fruit is published by Particular Books, London, 2014.