“Crowded Times” is the title of an exhibition of posters currently running at the Hungarian National Museum (until 25th August). The works chosen all come from the museum’s extensive collection and span the period from 1896, the year of the Magyar Millennium (when Hungary celebrated 1000 years of existence), to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The exhibition’s scope, in other words, is the birth and burgeoning of the consumer age, the heyday of the hoardings, when goods became mass-produced and more widely available, when services were allocated to all by a welfare state, and when information promoting each was disseminated by posters and placards, run off the printing presses in identical batches and plastered up on street corners or at bus stops, beamed from cinema and TV screens, invading the lives of everyone and creating a shared vocabulary of brand names, slogans and catch phrases. The poster becomes at once the mouthpiece of big business, the tannoy of the nanny state and a herald of the good life.

Posters, obviously, are designed to deliver loud, clear messages and this instantly enjoyable exhibition gets away with relatively few wall texts. The material is organised in three sections: consumer goods and services; leisure and entertainment; politics. The very first posters are pieces of domestic propaganda, celebrating national achievement and boasting of productivity. The posters from the Communist years do much the same (with the difference that in c. 1900, Budapest was second only to Minneapolis in the output of its mills, whereas half a century later the heroic worker is shown wielding a hammer that looks technologically Neanderthal). The posters in the first section include numerous advertisements for shops and products: some of the brands are still familiar (Dreher beer), others were done to death by nationalisation after WWII or privatisation after 1989. There are “Buy Hungarian” campaigns—often making a virtue of necessity, as in the case of the aluminium ads, extolling a material that was domestically produced in an age when imports were low. In almost every case, the division between advertising and propaganda is finely blurred. The posters are trying to tempt us (“Buy powdered egg—it never goes off!”) but also trying to control our behaviour and our thoughts (“Clear up trash to control flies!” “Down with the monarchy!”).

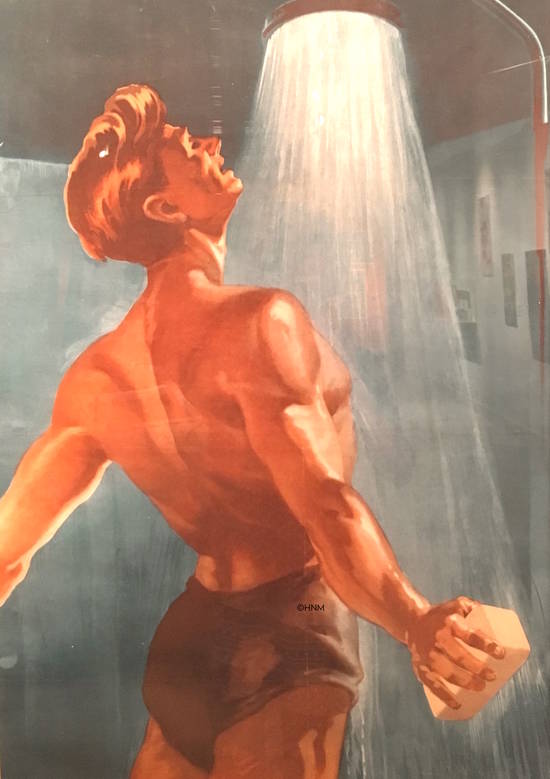

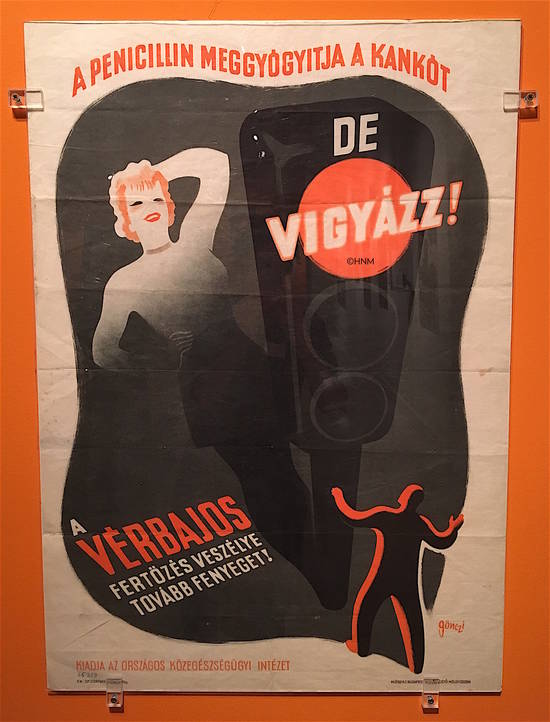

Some of the most amusing posters are those in the section on public health campaigns. A muscle-bound youth takes a bracing shower because cleanliness is the route to health (1939; illustrated above). A young man caught in the glare of the red light is sternly warned that “Penicillin can cure the clap—but watch out! You’re still at risk of syphilis!” (1949).

The poster is a democratic art form. In a way it is the contemporary era’s equivalent of the church altarpiece, a backdrop that is free for all to see and that we can’t help having to look at. Subtly, inevitably, it informs our attitudes and creates a collective conscious. Let’s not fool ourselves that ours is a non-religious age. A priestly class still governs us with their shibboleths and the promise is still elysian rewards if we do as we are told and misery if we don’t:

“Who may not be a Trade Union Member? He who exhibits anti-democratic behaviour, who lives an immoral life, who exhorts his co-workers to underproduce…” (Hungarian propaganda poster of 1948);

“Know ye not that the unrighteous shall not inherit the kingdom of God? Nor thieves, nor the covetous, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor extortioners…” (St Paul’s first Letter to the Corinthians).

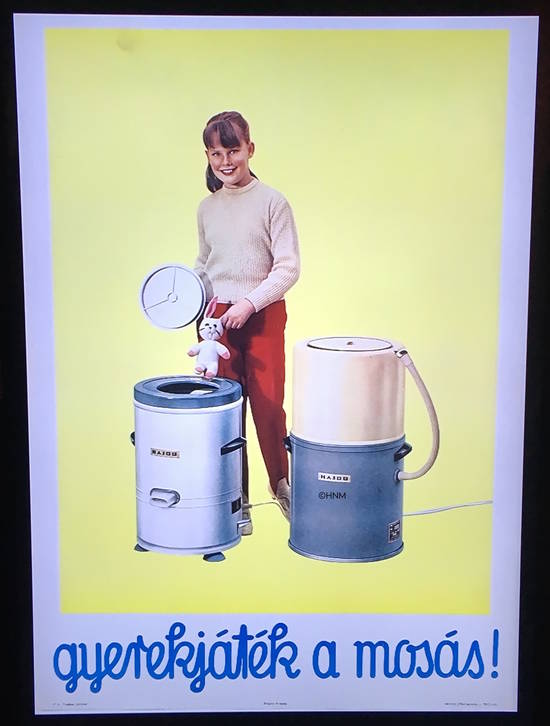

We might scoff at these visions of the ideal and at the preaching, but after an elapse of time, on seeing those familiar images again, they provide a fund of bittersweet nostalgia. Visitors to this exhibition react with touching delight at the sight of so many once-familiar things, like being reunited with long-lost friends. I felt much the same when I saw the ad for the revolving cylinder washing machine made by Hajdu. I had one in my very first Budapest flat.

In fact, what comes across very strongly across this entire, absorbing show, is how little in human nature and human behaviour has changed. Advertisers still target harassed housewives (convenience foods, miracle white goods), children (sweets and fizzy drinks) and the vain and aspirational (glamorous clothes that will turn heads, home furnishings that will impress the neighbours). Governments—despite overtourism—still try to mass-sell their capital cities using all the same old baited lines. The Fishermen’s Bastion and cruises up the Danube are as strong selling points for Budapest today as they were four or five decades ago.

The final room has a video loop of mass demonstrations, rallies and vigils, projected on a screen split into three separate strips to give a jerky image that perfectly imitates the scrapbook, snapshot nature of human memory. Ranged along one wall is a chronological series of political posters, beginning with Mihály Bíró’s powerful anti-war image of 1912. There is pro-Communist propaganda, pro-Horthy propaganda and an anti-Soviet poster which interestingly has no known artist, no printing house and no date.

Many of these posters are also superlative works of art. The curator has very properly credited every poster to its artist (where known) and at the end of the show there are brief biographies of some of them. Géza Faragó (1877–1928), who studied in Paris and worked for a couple of years with Mucha; Mihály Bíró (1886–1948), artist of the labour movement; Tibor Pólya, Imre Földes and others.

We may never see their like again. The conclusion of the exhibition is that the great age of the poster is over, not only because digital technology addresses us in different ways but because it has fragmented us, hiving us off into our own little circumscribed Snapchat groups and Facebook echo chambers. And yet… On leaving the museum and plunging into the Metro, I came face to face with a visual admonishment: “Never drink drive!” It was made in 2018 with the support of the FIA (Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile). Identical in spirit to “Alcohol is dead—don’t let it come back to life!”, a message (featured in this show) from 1919.

If you’re in Budapest this summer, make time for this exhibition. It’s a fascinating exposition of behavioural psychology (as well as being good fun).