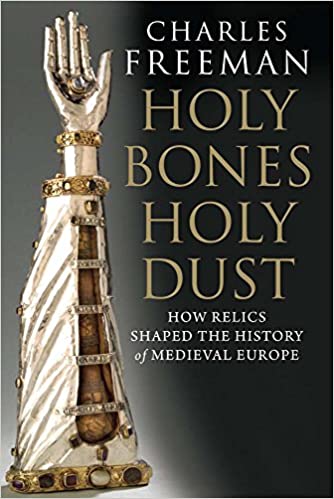

The latest book by Charles Freeman, freelance academic historian and historical consultant to the Blue Guides (published by Yale University Press, 2011; ISBN 978-0-300-12571-9).

The subtitle, ‘How Relics shaped the History of Medieval Europe’, sounds more universal than it actually is: the relics in question are exclusively Christian; the book makes no mention of the hair from the Prophet’s beard in Istanbul, for example, nor of any shrines there may have been in Muslim Spain. This is not a criticism; it is simply a fact that helps one to know what one is getting. We are talking about early Christianity, a subject on which Mr Freeman is extremely knowledgeable (and no less opinionated).

The book is a splendid read. It begins with a stirring account of the murder of Thomas Becket and goes on to examine the multifarious and mysterious ways in which early Church Fathers got distracted from the task of helping their flock to follow Christ’s model and fretted instead about whether the Holy Foreskin needed to have been rejoined to Jesus’ body after the Resurrection, or whether women entered Heaven in male form, as being representative of a higher state of being.

Freeman is particularly good on the vulnerability of relic cults to the onslaughts of science. ‘When an earthquake hit Venice in 1511,’ he tells us, ‘the Patriarch interpreted it as a sign from God in response to the increase of sodomy in the city. After all, the city’s prostitutes had been complaining that their own business was suffering as a consequence of this diversion in sexual behaviour. The diarist Marino Sanudo, who recorded the earthquake with his customary detachment, noted that the ensuing days of fasting, procession and preaching might have helped improve piety, “but as a remedy for earthquakes, which are a natural phenomenon, this was no good at all”….Sanudo is reflecting a growing understanding of the natural world.’

And yet, and yet… We may enjoy a little giggle at the idea that St Helena of Athyra possessed a ring that could quench sexual passion and owned a handkerchief that cured toothache, but how many of us have fondled crystals, tied copper bangles to our wrists, kept a scarab beetle in our pockets? The human need for tangible totems or amulets is as strong today as it ever was. A large part of the immense appeal of Freeman’s book is that it reminds us all of this foible. Which, on the scale of foibles, is a relatively harmless one. To the medieval mind, ‘Relics are the portents of heaven shining in their glory among the dross of sinful humanity.’ Nowadays we grope after transcendence in a variety of other ways. But the hope of shining glory is undimmed.

Reviewed by Tonsor

Charles Freeman is the author of Sites of Antiquity: from Ancient Egypt to the Fall of Rome, 50 Sites that Explain the Classical World, published by Blue Guides.