The name Lesley Blanch drifted into my consciousness in Italy in the late sixties. I cannot remember whether it was her book The Wilder Shores of Love or someone who knew her that came first but I had soon dug out her book, by far the most famous of several she wrote, and was absorbed by it. Blanch tells the story of four 19th-century women who sought emotional fulfilment in the Orient and it is a masterpiece, not only for the vigour and sensitivity of the writing but also in the way that Blanch’s own yearnings for exoticism and mystery travel with her subjects, from the penniless Isobel Arundel, obsessive lover and later wife of the scholarly vagabond Richard Burton, to the racy Jane Digby, escaping scandals at home and eventually marrying, as her fourth husband, Sheikh Abdul Medjuel El Mezrab, whose family controlled the land around Palmyra in the far east of modern Syria.

Few in the early 21st century would have imagined that Lesley Blanch was still alive but she lived until 2007, dying in the south of France at the age of 103. A devoted god-daughter, Georgia de Chamberet, has now put together fragments of the autobiography and memoirs that Blanch never published and, as one might expect, it is an extraordinary story. The single child, who appears to have arrived much to her parents’ surprise, began an apparently unexceptional life in Chiswick in west London, then still undeveloped, with marshland and a miscellany of fishermen’s huts and grander houses along the Thames. Yet an exotic visitor to her home, Theodore Komisarjevsky, a theatre designer, always known as ‘The Traveller’, inspired her fascination with travel to the East. ‘The Traveller’ became her first lover when she was seventeen, seducing her when she was supposedly being chaperoned in Paris. She was now on her way, studying at the Slade and earning a living from painting before she began her writing career as Features Editor at Vogue in 1937. Several of her pieces are included here, from the specific nature of British ‘cold’ to the versatility of Noel Coward.

The most extraordinary part of her memoir describes her marriage to Romain Gary. Of somewhat mysterious Russian birth but brought up in France, he had distinguished himself as an aviator in the circle of De Gaulle. The couple met in London during the war at a party given for the Free French. Gary was irresistible to women, un grand coureur, and their relationship could hardly have been anything but volatile. Hypochondriac, prone to self-dramatisation, an égoiste enragé, all too ready to withdraw into himself, he was simply impossible. Yet his diplomatic career took them from Bulgaria and Switzerland to New York and Los Angeles, eleven postings in all, while he sustained a highly successful career as a writer—alone in having won the Prix Goncourt twice. Only someone of extraordinary tolerance could have sustained him as long as Blanch did. He eventually deserted her after seventeen years of marriage for the actress Jean Seberg, but her frank account of their tortuous relationship is fascinating.

Blanch had a passion for objects. Already, aged seven, she had acquired a painted box, perhaps of Persian origin, to keep her sweets in. ‘The Traveller’ gave her a Fabergé egg and by the time she ended up alone in the south of France, her house was drenched with silks from Afghanistan and rugs from Aleppo. A library of early travel books on Russia and the Islamic world filled her shelves alongside icons and manuscripts. A small wooden frog, later identified as the tobacco-holder of a Baltic sea-captain, captivated her. And then in April 1994, fire swept through her house destroying almost everything. Bizarrely one of the few survivors among the ashes were photographs of Gary as a boy and his mother, entrusted to her when they first met and kept by her after their divorce. ‘Romain was once more demanding the limelight.’ The photographs are reproduced here.

This is an affectionate and engaging collection of pieces. From Marlene Dietrich cooking Blanch omelettes and conspiring with her (unsuccessfully) to obtain a burial plot in a little Russian cemetery outside Paris, to a gossipy relationship with Cecil Beaton and a scene with Truman Capote lying across her knees, there is much to feast on. It certainly should get us reading or rereading The Wilder Shores of Love.

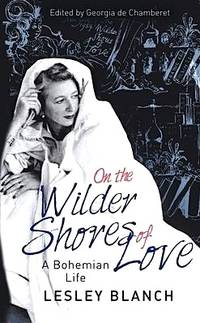

On the Wilder Shores of Love: A Bohemian Life, edited by Georgia de Chamberet, London, 2015. Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides and author of Sites of Antiquity.