This summer’s most charming show in Budapest is an exhibition at the Capa Center of colour photographs by Jacques-Henri Lartigue (1894–1986).

Lartigue, the son of an amateur photographer, received his first camera at the age of nine, a present from his father. He went on to take photographs all his life, encouraged by his father, who gave him support and equipment and, when he was 18, a Pathé cinecamera.

Lartigue neverthelesss chose a career as a painter and—at least to begin with, partly thanks to his vivacious and well-connected first wife Bibi—enjoyed a successful career in painting and set-design, hobnobbing with artists, writers, journalists, people from the world of film and the theatre, and all kinds of bohemians and hangers-on—not to mention a wealth of minor and major celebrities, as the shot of Cocteau and Picasso at a bullfight in 1955 makes clear.

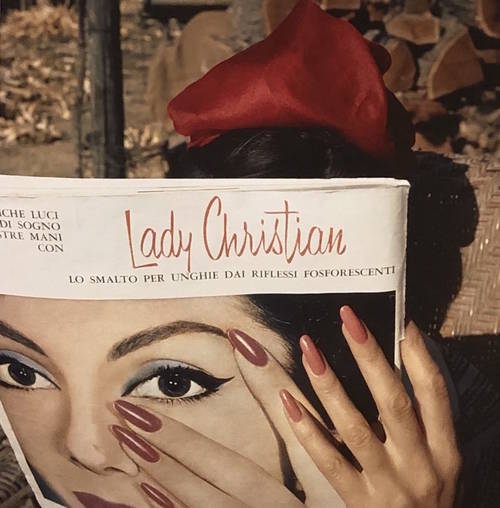

Lartigue’s colour photography is so refreshing because it reflects little of this life-in-the-fast-lane image. What we see are candid shots of his friends and family, wives and lovers, the view from his bedroom window, holiday snaps, everyday scenes: the sort of thing people might put up on Facebook today, in other words, though snapped with a much acuter eye than most, as the shot above, of his third wife Florette’s painted nails holding open an Italian magazine with an advert for nail polish (1961), amply demonstrates. There is an an honesty and a joy in everything captured by Lartigue’s lens. The 20th century that he presents is an era of imperceptibly-occurring but irreversible change, an end of innocence—and at the same time an age of unaffected beauty and instinctive glamour. Unlike the century that the history books reveal, the photographs in this show present an age of fun and laughter.

Lartigue’s colour photographs were exhibited for the first time in 1954. The real break, though, came in 1962, when Charles Rado (a Hungarian, incidentally), founder of the Rapho photographic agency, showed a body of Lartigue’s work to John Sarkowski, head of photography at MoMA. A solo exhibition and a feature in Life magazine followed. Lartigue’s fame was assured.

The earliest photographs in this show are family lineups from 1912–14 in Pau, Chamonix and elsewhere in France. We also see soft-focus shots of Bibi, with pink roses and red lipstick, and then again at a corner table with a wide sea view in the Cap-Eden-Roc hotel in Antibes. It is impossible to give highlights. Different shots will appeal to different people. Mine were a grim-faced nun lugging an invalid in a dog-cart to Lourdes (1957), laundry flapping wildly outside slum dwellings in Rome (1960), a solitary cyclist on the Appian Way, an elderly Breton widow in traditional black cylindrical headdress sitting incongruously under a red beach umbrella with a bottle of commercial orangeade and a garishly plastic, duck-shaped swimming ring (1970). Striking too is the view of the snowbound Mégève viewed through a gigantic ice-beaded spider’s web and a Palladian villa at Dolo on the Brenta Canal between Venice and Padua, looking, in 1958, utterly derelict and desolate. Today, spruced up, that same villa offers B&B.

Between 1979 and his death in 1986, Lartigue bequeathed his entire photographic oeuvre to the French government. How fortunate that this body of private, intensely personal work did not find its way into a rubbish skip! As the shot of “Florence Pauly, my paintings”, taken in Havana in 1957, shows (though unfortunately, for copyright reasons, we can’t show the image here), Lartigue deserves more from posterity than to be remembered purely as a painter of floral bouquets.

“Life in Color”, an exhibition of the colour photographs of Jacques-Henri Lartigue, runs at the Capa Center in Budapest until 1st September.