In 1900 the archaeologist Giacomo Boni uncovered some intriguing remains in the Roman Forum: those of the so-called ‘Oratory of the Forty Martyrs’ and, leading off it, a covered brick ramp. These remains are usually closed to the public, and work on them is ongoing, but at the moment (until 10th January 2016) they are open as part of an exhibition.

From the street which runs alongside what would once have been the entrance portico of the great Basilica Julia (an opposite the modern public toilets), a path leads to the excavations. The Oratory, its walls covered in fragmentary frescoes, has been enlosed by a modern roof, walls and door. At first sight, you might think there is nothing remarkable about these, but signboards explain the enormous trouble that has been taken to reconstruct what might originally have been in place here: a roof which rises above the ground at the same height as the ceiling of the ramp, a door whose dimensions conform to those of ‘Golden Rectangle’, and an interior volume that, like that of the Pantheon, is exactly as tall as it is wide, so that a perfect sphere could be fitted inside. The room itself, today known as the Oratory because of its later use as a place of Christian worship, was originally constructed in the 1st century, at the time of the emperor Domitian, to form an entrance vestibule to the ramp, the covered walkway which slopes and winds its way gently up to the Palatine Hill, linking the Imperial palace and the Forum.

The ramp and its ancillary buildings were added to by succeeding emperors so that by the time of Hadrian in the 2nd century the complex consisted of the ramp itself, two separate vestibules and a grand porticoed atrium. The current exhibition has opened the ramp and the first vestibule, the Oratory of the Forty Martyrs, to the public.

The ramp is similar in its design to that inside Castel Sant’Angelo, the ancient mausoleum of Hadrian, which winds through the core of the building to the central sepulchral chamber. It is tall and narrow and barrel-vaulted, its walls and floor made of brick. It would have been possible to travel along its length on horseback. Rooms that open off it might have been used by the Imperial guard. They have been arranged to exhibit pieces of sculpture found during excavations. At the level of the first landing, on the right, are the remains of a latrine, built during the time of Hadrian and close to a staircase inserted under Hadrian’s predecessor Trajan to link the grand atrium or forecourt to the ramp. In the early Christian era, this atrium was turned into the church of Santa Maria Antiqua, and it is known that the staircase was still in use at that time. The ramp leads onward and upward, out into the sunlight again, to an elevated terrace from where there is a magnificent view of the Forum down below and across the rooftops, domes and bell-towers of the city. The continuation of the ramp from here to the summit of the Palatine is not open, and indeed excavations are not yet complete. It is proposed at a later stage to open it up and allow public access.

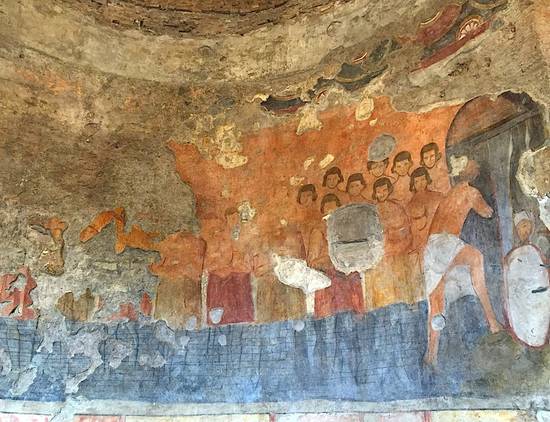

The Oratory of the Forty Martyrs has interesting traces of fresco decoration. Each of the four walls was decorated with a dado of trompe l’oeil white drapery, above which are figurative scenes. On the wall on the left as you enter (the north wall) are the very scanty remains of the Forty Martyrs in Glory. You can still make out some of their heads, encircled with haloes, and their bright white robes, edged with purple like a magistrate’s toga. The east wall, with an apse at its centre, has the main scene. The Forty Martyrs were Roman soldiers of the Legio XII Fulminata, who had converted to Christianity. They were sentenced (in AD 320) to spend the night naked in a frozen pond, near which were warm baths, specially prepared to tempt any who might wish to recant rather than die of exposure. One of the company did so: the fresco shows him sneaking away from his companions to thaw his frozen limbs. His action left only thirty-nine faithful, until one of their guards came forward and confessed his Christian faith, taking the number back to forty again. To the left of this scene are large painted crosses, hung with jewels, and below one of them, a peacock, symbol of immortality. The south wall had scenes of monastic life (very ruined). The frescoes have undergone several restorations between 1969 and today. For this exhibition, they were restored (very beautifully) under the leadership of Susanna Sarmati.

by Annabel Barber. See here for Blue Guides on Rome.