Walking seems to be back in fashion. Pilgrim routes, secret pathways, ancient trackways: it is as if we are rediscovering the traditional pace of life. One catalyst for the interest has been Patrick Leigh Fermor’s celebrated walk across Europe, from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul, in 1934, when he was only eighteen. It was immortalized in his two books A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water. Although they are among my favourite travel books, I had not realised quite how long after the walk they were written. A Time of Gifts appeared 44 years later and Between the Woods and the Waterseveral years after that. So they are as much reflections on the walk, with added colour and insight, as they are of the reactions of an eighteen-year old.

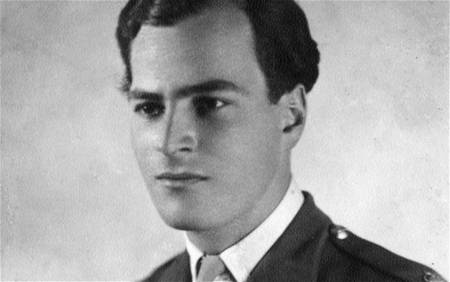

Virtually abandoned as a child in England by his family—his father had a distinguished career as a geologist in India—Paddy (the name by which his biographer and his many friends knew him) grew up essentially feral. School did not work for him and he seemed unemployable. Yet he had a passion for the Classics, an acute memory for texts and a fascination with languages and how they shaped cultures. All this was incipient when he began his walk, but as he uncovered the ancient landed families of eastern Europe, explored their libraries and became a lover, notably of Princess Balasha Cantacuzene on her remote estate in Romania, he discovered new roles for himself. He was always to be a wanderer, attracted to the aristocracy as much for their heritage as for their status, ever willing to be financially supported, and happy to drink and sing his way through the night in a variety of languages and cultures.

When war came, it was again apparent that Paddy was not employable in any conventional role; but with his fluent Greek he could be found a job as a general dogsbody in Intelligence. This is how he ended up supporting the resistance in Crete against the occupying Germans. His most famous exploit, kidnapping the German commanding officer, General Heinrich Kreipe, forms the narrative highlight of this book. The moment when Paddy was able to complete a Horatian ode begun by the General is an unforgettable homage to the common roots of both cultures. Of course, with reprisals against villagers and Paddy’s own careless shooting of a partisan with a gun he thought unloaded, the kidnapping remains controversial, but for many Cretans Paddy was a hero. Hard-drinking reunions followed in the years to come.

Artemis Cooper knew ‘Paddy’ well, but her subject still presents a challenge. Cooper is wise enough not to try to match Paddy’s style when describing the famous walk and is content to tidy up discrepancies and fill in gaps. The kidnapping of Kreipe is well told. The problem comes with the years that followed. There is certainly good material for charting Paddy’s sophisticated survival skills, his charm and success in persuading others to finance him (notably his long-term lover and eventual wife, Joan). It is moving to read of the shattered lives of his friends and lovers, Balasha among them. Full tribute is paid to his publisher, Jock Murray, whose guile and persistence ensured that the books actually appeared. Most publishers would have abandoned Paddy in sheer exasperation at his penchant for parties over disciplined writing.

Cooper also hints at the darker side: the depressions, the sexual dalliances—some of them actually encouraged by Joan—and at Paddy’s ability as much to bore his listeners as to amuse them. And yet somehow she does not capture the full personality. The chronology is there, the house in the Mani is built (at Joan’s expense), the wanderings are well charted, but the subject remains strangely elusive. Doubtless there are more perceptive and probing memoirs to come, but this biography provides a solid background and serves well to send one back to Paddy’s writing, not only the famous walk but also the vivid studies of Greece, Mani and Roumeli. And we are promised that the fragments of the third volume of the walk, awaited by his readers for so long, are due to appear next year.

(One correction. Paddy’s friend was Ian Whigham, not Wigham. He was a man of fastidious good taste and generous hospitality: I count the two occasions when I had lunch with him, as a friend of a friend in the 1970s, as among the more civilizing experiences of my life.)

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides and author of Sites of Antiquity: 50 Sites that Explain the Classical World.