A swift tour of the Uffizi’s newly-opened Red Rooms by Alta Macadam, author of Blue Guide Florence.

The Sale Rosse are a suite of nine rooms (nos 56–66) on the piano nobileof the Uffizi, opened in June this year. They are marked on this plan on the Uffizi website (which also takes you on a virtual tour). The rooms display some ancient Roman sculpture and Florentine paintings from the early 16th century, most of which was formerly displayed elsewhere in the gallery.They overlook the courtyard and have large windows providing excellent lighting. Each room has a bright red wall (hiding the climate control apparatus) on which the most important works are displayed (perhaps not an ideal solution). Labelling is kept to a minimum.

The first room (56), the only one entirely painted crimson, has an impressive display of early-Imperial Roman replicas of famous Hellenistic sculptures. They include a marble replica of the Capitoline Spinario, the Farnese Hercules, and the Gaddi torso. They have been exhibited here to underline the influence that they had on Florentine painters of the early 16th century (pointed out by Vasari), notably Andrea del Sarto, whose works are hung in the first two rooms. His three chiaroscuro scenes, on show for the first time, show his skill and interest in representing the Classical style. His Madonna of the Harpies, with its carved Roman base, is also a direct citation of ancient Rome, and other altarpieces by him are displayed in the same room, as well as his delightful portrait of a young lady with a book of Petrarch (formerly displayed in the Tribuna). Room 59 has Domenico Puligo’s splendid portrait of Pietro Carnesecchi, a male portrait by Franciabigio, and three scenes by Bachiacca.

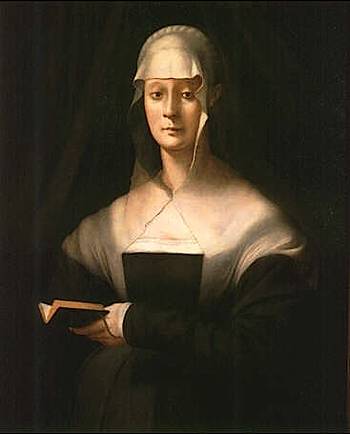

Rosso Fiorentino is for the first time given a room to himself (60), although the extraordinarily powerful Moses defending the daughters of Jethro from the shepherds is still only attributed to him. His endlessly reproduced Angel Musician is in fact only a fragment, and the portraits displayed here are only tentatively attributed to him; it is suggested that one of them may be by Giovanni di Lorenzo Larciani, who also painted the exquisite little Allegory of Fortune hung here. Portraits by Pontormo in Room 61 include his well-known (posthumous) portrait of Cosimo il Vecchio, dressed from head to foot in crimson, which used to hang in the Tribuna, and his very fine portrait of Maria Salviati, who was his contemporary and the mother of Cosimo I (b. 1519). Maria was widowed at the age of 27 and devoutly dressed as a nun for the rest of her life, hence her portrayal as such here. Her tomb in the Medici Chapels, and that of her husband, Giovanni delle Bande Nere, have been investigated this month in an attempt to solve the mystery of Giovanni’s death: it seems his foot was amputated following a battle-wound but he died shortly afterwards of septicaemia). Two other lovely portraits hung here were formerly atttributed to Pontormo: the woman with a basket full of spindles by Andrea del Sarto, and the musician by the much less well known Pier Francesco di Jacopo Foschi.

Rooms 64 and 65 display all the great Medici family portraits by Bronzino, which include his masterpieces, most of which were formerly in the Tribuna. Here they can be seen in a far better light and in all their glory. Amongst them are the newly restored refined portraits of Bartolomeo Panciatichi and his wife Lucrezia, fittingly displayed on either side of the “Panciatichi” Holy Family. Eleanor of Toledo, in a splendid velvet dress with her son Giovanni, is shown in a very sophisticated work, whereas the delightful young Medici children are portrayed in much more natural poses. A bizarre note is struck with the full-length nude portrait of the dwarf Morgante: it is displayed in the centre of Room 65 as it is amusingly painted both on the front and the back.

The last room (66) has a superb group of paintings by the greatest master of this period, Raphael. His famous portrait of the first Medici pope, Leo X, with his two cousins whom he created cardinals, hangs beside his self-portrait and his court portraits of the Gonzaga and Della Rovere. But perhaps the most memorable painting of all in this set of rooms is his famous Madonna del Cardellino (“Madonna of the Goldfinch”), which was spectacularly restored a few years ago.