At last, after several years of closure for renovations and transformations, the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest is emerging from its chrysalis of scaffolding and tarpaulin. Stretching out its wings to dry at the moment is the Romanesque Hall, a spacious rectangular room inspired by the basilica architecture of Early Christian Europe. Newly restored, it is open to the public for free visits until 2nd April.

Information about the Romanesque Hall in the press tends to concentrate on statistics: how many years it has been closed for (70); how many kilos of gold were spent on the refurbishment (5.5); how many more square metres of space the museum will gain after all the restorations (2,000). And logistical details about the new café, the lifts, the disabled access and the solar panels. Hurrah! But what about the Romanesque Hall itself?

It is open now for just a few more days. After it closes again, it will not reopen until October. So, until then, here are some photos and a description.

The Museum of Fine Arts building as a whole was completed in 1906, the decorations of the Romanesque Hall a couple of years previously. The entire edifice was conceived as part of an elaborate scheme of celebrations concocted in 1896 to mark the (approximate) thousandth anniversary of the Magyar occupation of the Carpathian Basin. Unsurprisingly, the decorative programme draws from Hungarian history as well as from European architectural precedents.

The hall is a large rectangle, paved in a geometric pattern of yellow, red and grey. It is entered through double doors framed by a cast of the Goldene Pforte, the Romanesque west doorway of Freiberg cathedral (c. 1225). Elaborately moulded round arches are borne on pillars bearing statues of Daniel, the Queen of Sheba, Solomon and John the Baptist (left) and Aaron, Bathsheba, David and John the Evangelist (right). Above, in the tympanum, is a scene of the Adoration of the Magi. When it first opened, the whole hall was used as a cast gallery, displaying copies of some of the most famous works of antiquity and the Renaissance. Today just this portal remains, and one other, at the head of the left-hand ambulatory, a copy of the south door of the church of St Michael in Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia), Transylvania.

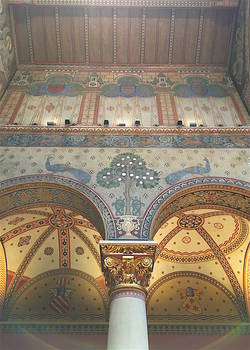

The rectangular space is articulated internally by an arcade which creates a sort of peristyle effect, giving an ambulatory on three sides. The arcade is borne on stout columns alternating with square pillars decorated with trompe l’oeil rustication. The column capitals are richly carved and gilded. The motifs are mainly floral but there are also capitals with paired birds pecking at grapes, stylised owls and stags. Above the square pillars rise two triumphal arches, spanning the inner space and adorned with pairs of painted Hungarian saints (Stephen and Ladislas on one; Margaret and Elizabeth on the other), with signs of the Zodiac in the soffits.

The walls are completely covered in painted decoration. On the long sides are Hungarian kings and heroes and coats of arms. Between them are peacocks (symbols of immortality) and trees bearing silver fruits, reminiscent of the design of the 12th-century mosaics in King Roger’s room in Palermo. Latin words in ‘Gothick’ script exhort us to occupy ourselves with Truth, Science and the Arts. Our rewards, presumably, will be the glories promised on the other side: Eternity, Omnipotence and Immortality.

On the short wall above the Goldene Pforte is a painted roundel of the Virgin and Child flanked by angels holding Gothick Latin legends. At the opposite end is a matching roundel of the Good Shepherd, and more angels with Gothick legends in Greek: ‘God is Holy’; ‘Strong, Holy, Immortal’. Between the angels, at each end, is a three-light blind aperture with colonnettes divided by trompe l’oeil drapery. The drapery device is continued all around the top of the walls, below the line of the simple pitched roof. Above it rise painted towers and battlements. The iconography here is all derived from mosaics in early Christian churches.

But this is a secular space. The primary aim of its decorative scheme is to demonstrate Hungary’s position at the heart of Europe, an integral part of the continent’s history as well as its artistic and cultural traditions. It is a testament to an age of optimism, confidence and self-belief.