People often worry that a trip to Venice will be marred by excess numbers of their fellow human beings. True, the city gets very crowded at certain times of year, and yes, there are ever fewer Venetians and ever more wretched carnival mask shops. But overcrowding afflicts only St Mark’s Square, the Accademia Bridge (and the route between the two), the Riva degli Schiavoni, Rialto and sometimes the island of Murano. Other parts are as tranquil as they were when Ruskin came to sketch them. Below are our top ten favourites (list still in progress).

1. San Trovaso: Plenty of people know about the squero, the gondola yard on the Rio San Trovaso in the sestiere of Dorsoduro. Opposite, on Fondamenta Nani, the bàcaro known as Schiavi or Vini al Bottegon is even more celebrated. It features in every single guide book. The ciccheti are superb, it is true, and the range of wines extraordinary, but the crowds at the bar are often more than the tiny place can comfortably handle. What gets overlooked is the large church of San Trovaso itself, with its two huge Diocletian windows, looming over its eponymous campo. It is not by Palladio, but probably by a pupil. Inside there are two Tintorettos and, which always delights me, an altar (just to the right of the west door) dedicated to the guild of gondola-builders. I like to think of them popping in for a quick prayer before or after work at the shipyard just outside.

2. Palazzo Querini-Stampalia: Approached across a narrow canal from Campo Santa Maria Formosa in the sestiere of Castello, this 16th-century palace has interesting interiors, a good collection of paintings (particularly 18th-century documentary views of Venice) and an excellent bookshop. The ground floor was remodelled by Carlo Scarpa and is an interesting example of his work. Perhaps his best. An exhibition documenting Scarpa’s time as director of the Venini glassworks is running on the island of San Giorgio until 29th November. See here for details.

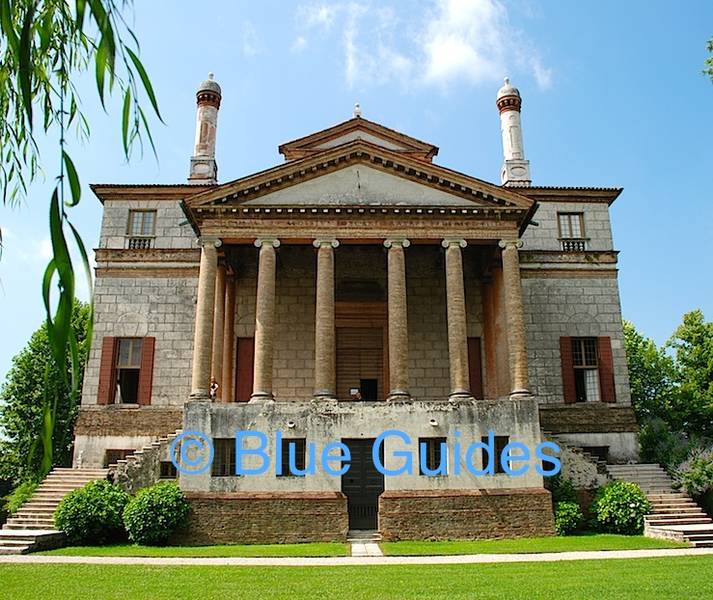

3. La Malcontenta: True, this famous villa is not in Venice: it stands on the bank of the Brenta canal, a narrow, tranquil waterway that runs between Venice and Padua. But to understand Venice in her heyday, you need to come and see these villas. Their Palladian design is serenely perfect, the relationship between building and nature graceful and inspiring. From the 16th century onwards, patrician Venetians would pack up their town houses and travel by horse-drawn barge, the burchiello, up the Brenta to their summer villa. For the more academically minded this would have meant total repose, and the opportunity to brush up their Greek, study their astrolabes, write treatises on the whooping cough, etc. The more social would have thrown competitively magnificent parties in competitively fragrant gardens and Veronese-frescoed salons. La Malcontenta herself, Elisabetta Foscari, was exiled to this villa by an outraged husband no longer disposed to tolerate her licentious lifestyle. One can imagine her sitting in one of the cushioned window-nooks, gazing sourly and sullenly out at the little willow-shaded curve of the canal whose view her great villa commands. Today a motorised burchiello still runs up the Brenta, between March and October, from the Pietà landing stage in Venice. For details, see www.ilburchiello.it. The Brenta and its villas are covered in Blue Guide Concise Italy and Blue Guide Northern Italy.

4. Santo Stefano: The church of Santo Stefano is one of the finest in Venice. From a distance, its slightly leaning bell-tower is a landmark. It stands in the busy Campo Santo Stefano in the impossibly busy sestiere of San Marco. But inside, it is a haven of quiet. It is one of the churches belonging to the Chorus Pass scheme, which means you have to pay a small amount to get in. And not everyone chooses to do so.

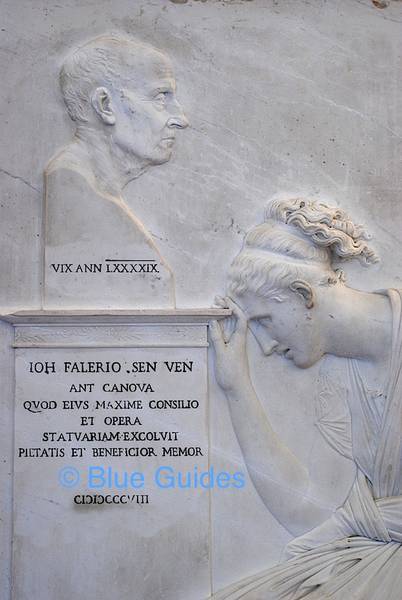

Santo Stefano has long been linked to Venice’s mariners. In the floor of the nave is the huge seal of Francesco Morosini, the Admiral of the Fleet who captured the Peloponnese for Venice (and who also inadvertently blew up the Parthenon during the Siege of Athens in 1687). The guild of bakers, the pistori in Venetian dialect, were attached to this church. Their dry ship’s biscuit was especially prized by the Republic’s quartermasters. As if to emphasise the maritime connections, the church has a magnificent wooden ship’s keel roof. There are four paintings by Tintoretto in the sacristy: Washing of the Feet, Resurrection, Prayer in the Garden and Last Supper (pictured, 4a. Is Judas the man on the left, turning away and guiltily grabbing at the wine?). In the adjoining small cloister is an exquisite bas-relief by Canova, the funeral stele of Giovanni Falier (pictured, 4b), the man who recognised Canova’s sculptor’s talent when he was still a humble kitchen boy and who became his first patron.

5. San Vitale: This church is a particular favourite of mine. It stands in a very crowded spot, on the busy thoroughfare between Campo Santo Stefano and the Accademia Bridge. The dedication is to St Vitalis, once reputed to have been a Roman soldier martyred by Nero but later outed as a figment of the medieval imagination, whereupon his cult was suppressed. The church is now deconsecrated and is used for concerts. But its door is always open and when there is no concert in progress, it is a place to see two wonderful works of art in situ. The main altarpiece, of St Vitalis on a white charger, is by Carpaccio (1514). While his works in the Scuola degli Schiavoni are often hard to view in peace because of the numbers of visitors in the tiny space, this luminous altarpiece shines out at you down the central aisle as you stand at the main west door. On the right-hand side is another fine painting, a typical brown-toned work by Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, showing the Archangel Raphael appearing in a glow of intense white light to Sts Anthony of Padua and Louis Gonzaga.