Visitors touring Ephesus might easily end their visit at the Terraced Houses, with their beautiful frescoes and opulent marble floors. The degree of preservation is stunning. Left to the elements frescoes do not survive undamaged to such a height but as there is no trace of immediate reconstruction as such, one is left to wonder how and why they were protected. Taphonomy (the way artefacts are accrued to the archaeological record) can shed light on the process.

The destructive event is dated to around AD 620, an act either of human aggression (the Sassanids) or a natural disaster (earthquake)—or indeed both. The damage was terminal: the houses were not repaired but nor was the site abandoned. A quick backfill followed and the location was terraced again, at an unspecified time, and occupied by a long narrow building, apparently used for storage. This is Late Antiquity, a time when archaeological evidence becomes quite scarce. Buildings, generally speaking, were flimsier constructions, while early excavators looking for solid Roman and Greek solid stonework tended to clear the surface of any later structure, skimp on recording and sometimes publish nothing. From this period on, archaeology is greatly assisted by historians—eminent among them Clive Foss—who have pondered over any available documentation from archives to travellers’ accounts, to graffiti, to piece together Ephesus’s trajectory from the fateful event in the early 7th century to about 1,000 years later, when the great metropolis truly died.

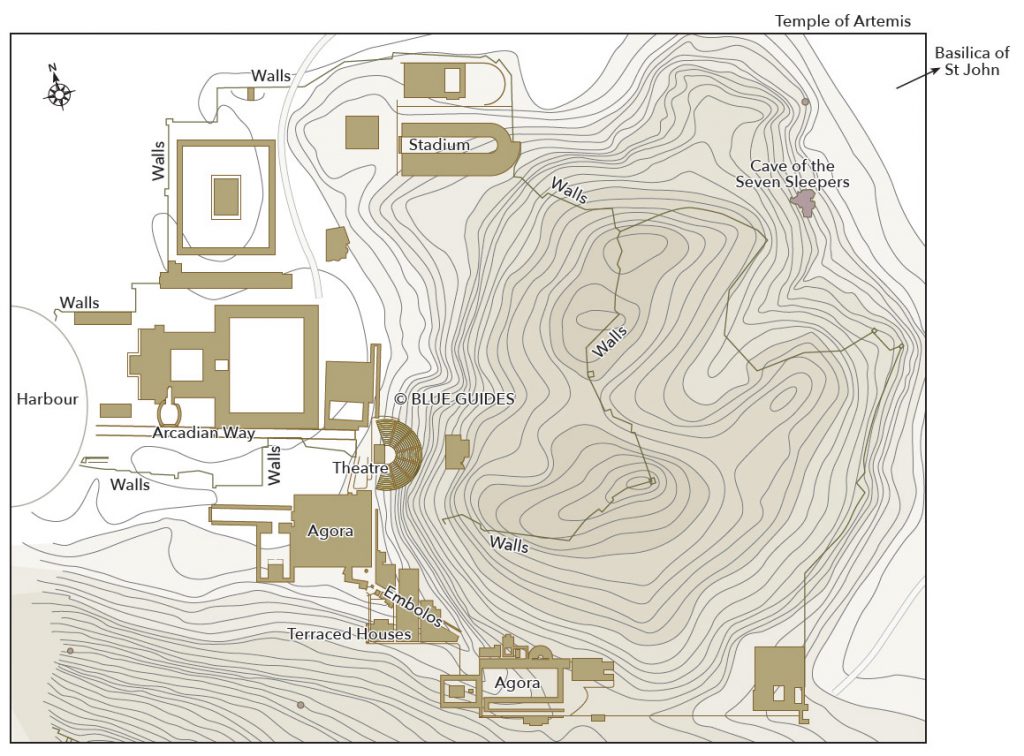

The next two centuries are in many respects a black hole, but one thing is clear: Ephesus regrouped and took a fateful decision. Defence came to the fore. Ephesus received a new set of walls that halved the size of the city, leaving out the whole of the Embolos and both agoras. All efforts were concentrated on the Harbour. The wall, 4m thick (squared stones filled with rubble), ran from the Harbour to the Theatre, along the Arcadian Way and up to the Stadium, and then back to the Harbour.

About a mile to the northeast, the barren hill known to the Byzantines as Helibaton (‘The Steep One’), where Justinian had built the grand basilica dedicated to St John the Apostle in about the mid-6th century, another Ephesus had developed, cashing in on the pilgrimage trade. St John had apparently died here and his grave lay beneath the altar. In addition to this, there was the Cave of the Seven Sleepers, a holy site for pagans, Christians and Muslims alike. And there was always the passing trade of pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land.

Helibaton, according to the archaeology, was not settled at the time; it was used as a necropolis, the oldest grave being Mycenaean. So, how come its fortune changed? Procopius, the contemporary historian, states very clearly that there was no water. One has to conclude that the aqueduct that made settlement possible dates roughly to the time of the grandiose church, another mark of imperial favour. A wall was built to defend the settlement, using spolia from earlier structures both nearby (the Temple of Artemis) and far away (the Stadium). In these new circumstances, Ephesus fared better than contemporary Sardis (a fortress and some villages) and Pergamon (a small fort). That was certainly the impression of Bishop Willibald, who visited on his way to the Holy Land in 721. After the great havoc of the Arab incursions, the ravages of the plague and other afflictions such as civic unrest, our bishop found Ephesus the capital of a thema (a Byzantine military and administrative district), functioning although diminished. In addition to trade, Ephesus had always had a rich and productive hinterland, not having in its Greek past dissipated its energies in setting up colonies, as Miletus had done.

The next 350 years of Byzantine presence mark a steady decline. By about the 10th century the harbour had silted up, making it no longer suitable for the Byzantine fleet. The fleet moved about ten miles south, to Phygela, an unexcavated Genoese colony also known as Scalanova, now covered over by the modern settlement of Kuşadası. Trade suffered. Tellingly it is about now that the whole of Ephesus started to became known as Hagios Theologos (from which later on it became Ayasoluk for the Muslims and Altoluogo for the Latins).

The time of Lascarid rule was particularly auspicious. This was when the Latins ran Byzantium, in the first half of the 13th century, and the ruling Byzantine dynasty was based in Anatolia. Borders were well defended by the akrites, a sort of elite caste of freelance fighters, and the marauding Turks from the east were kept in check. The walls of Ayasoluk were remodelled, with the building of a separate fortress with pentagonal and rectangular towers, the ancestor of the tower we can admire today. The great basilica seems to have fared less well: according to Bishop John Tornikes, it was full of hedgehogs, bird droppings and fallen mosaics. The atrium was covered in buildings. Indeed, while Ephesus emptied, Ayasoluk was bursting at the seams and expanding beyond the walls. The original trickle of nomads from the east, after the fateful battle of Manzikert 1071, was now turning into a flood down the Meander valley. Recent political developments such as the setting up of the Sultanate of Konya had upset the pattern of trade. Communication with the east was severed.

The incorporation into the Emirate of Aydın (which moved its capital to Ayasoluk) brought some sort of stability. Trade resumed, with Venetian and Genoese merchants looking for raw materials (alum, grain, rice, wax and hemp) in exchange for manufactured products such as the ever-popular brightly coloured cloth. The original harbour, now unusable, was abandoned. The new harbour (Panormus) was at a location four miles due west of Ayasoluk. A map drawn by Choiseul-Gouffier, French ambassador to the Porte from 1784–91, shows the spot just north of the mouth of the Cayster. It is labelled ‘Lake full of reeds’ and was at that time by the sea, whereas the present coastline is two miles further west. Older accounts mention merchants’ houses, docks, churches, a lighthouse and a ‘deep’ harbour around the eastern end of the inlet. Investigations have been sporadic. Merchandise could move by road and down the river. The local emir pocketed the dues and indulged in some piracy to supply the slave market. Times were prosperous. The Isa Bey mosque went up, the first monumental building in the area since the time of Justinian. The court of the emir patronised the arts and sciences.

St John’s basilica was turned in part into a mosque (the frescoes were hidden under coloured marble slabs) and the rest of the building was used as a market for the produce of the fertile hinterland. Locally minted gold coinage imitated that of Florence. By now the fame of St John had acquired an extra twist: not only did the sacred tomb beneath the altar exude a miraculous manna on certain dates, but the saint, it turned out, was not really dead. He was merely asleep, and his snoring could be heard. Pilgrims continued to flock to the sacred site and paid the entrance fee imposed by the business-minded Turks.

This sort of mutually beneficial cohabitation required a lot of delicate footwork, not least because the emir’s authority was never beyond challenge by other members of his family. The intervention of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezıt I (known as Yıldırım, the ‘Thunderbolt’) was as unwelcome as it was inopportune. He plunged the emirate into chaos in 1390. When Tamerlane captured him at the battle of Ankara in 1402, the Anatolian emirs breathed a collective sigh of relief. But the respite was short-lived. The Ottomans returned in 1425, and this time they stayed. Serious decline set in. Trade gradually moved to Scalanova and Izmir. Istanbul was distant and indifferent. Nomadism took root in the hinterland, with serious ecological consequences: deforestation, the neglect of drainage ditches and therefore increased silting.

Under the conservative Ottoman rule, Ephesus maintained its administrative role as the head of a kaza, an administrative division under a kadı (a judge); the mint still operated. Western travellers attracted by the Classical ruins had to go to Ayasoluk to find lodgings and to pay their respects to the kadı, a process that involved bringing a suitable gift (coffee and sugar were welcomed). Their accounts paint a dismal picture of the place: houses with earthen roofs, lodgings full of fleas, howling jackals; but the Isa Bey mosque was in good repair and was at times mistaken for St John’s basilica. Evliya Çelebi, who visited in the mid-17th century, was certainly not fooled. Finding little reason to rejoice in the present state of Ayasoluk, he berated the locals and their laziness for the sad state of affairs while at the same time conjuring up a mythical, glorious Islamic past when Ayasoluk had had 300 baths, 20,000 shops, and 3,800 mosques, both large and small. The reality was that the place was riddled with malaria, a fact greatly responsible for the misery witnessed by visitors.

By the 18th century the Turkish population had moved into the castle while the Greeks had decamped to the surrounding hills. By the 19th century the castle was in ruins but there was still a kadı; he lived in the village.

The planned railway put Ephesus back on the map as a communication hub, which had been its calling since antiquity. Its construction brought with it a young engineer, John Turtle Wood, who pinpointed the correct location of the Artemision and thereby started the rebirth of Ephesus.

By Paola Pugsley, author of Blue Guide Aegean Turkey: From Troy to Bodrum