The title of this engaging small exhibition, on show at the Museum of Trade and Tourism (MKVM) in Budapest, celebrates the centenary of the famous Gellért hotel and baths. Housed in magnificently tiled and decorated late-Art Nouveau halls, the baths are one of the most popular destinations on every tourist’s itinerary. But they still cater to a local clientèle too: as you line up for your ticket, you will see a special queue for people with doctors’ notes, coming here not purely for recreation but to take the cure. In this, the Gellért remains true to its roots.

The curative thermal waters on this site have been known for a long time. In the Middle Ages, St Elizabeth of Hungary used them to bathe lepers. The Ottomans prized the waters too: there was an open-air mud bath here, which, after the Turks were expelled, became a place where horses were treated for distemper and, by the 19th century, a resort of ill-repute. A new spa building was built in 1832 (in fact it is still there, under Gellért Square, though seldom open to the public) but it was not until the construction of the Liberty Bridge (originally Franz Joseph Bridge) over the Danube in 1896 that the area really began to take off. The bridge attracted the developers and the area was cleared. On show in the exhibition is a charming photograph of an improvised summer dance floor, pressed into a secondary role as a cowshed. This, along with numerous cottages, taverns and summer villas, all fell to the wrecking ball.

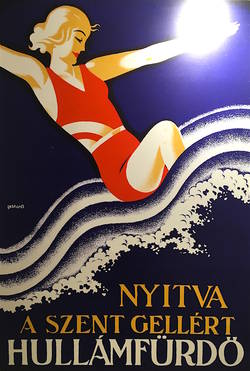

A tender to design the new baths complex was won by two architects, Artúr Sebestyén and Ármin Hegedus. Their designs were completed in 1909, on a floor plan by a third architect, Izidor Sterk. Construction, delayed by WWI, was completed in 1918. Vintage posters on display make it clear that the business of marketing Budapest as a ‘Spa City’ has been in full swing since the early 1920s. In 1927 a wave machine was installed in the outdoor pool (the original mechanism is still in operation) and in 1933 the palm court and mini-golf course gave way to an indoor pool and whirlpool.

The baths were always intended to be used for recreation as well as therapy and their decoration was lavish and opulent. The huge vaulted halls were designed to recall the massive, overarching spaces of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. Visiting the baths today, one is still reminded of an Alma-Tadema painting.

Budapest suffered greatly in both world wars and the Gellért shared the same fate. In 1919, Romanian army chiefs took over the hotel during their occupation of the city. When Admiral Horthy rode into Budapest later that same year, he used the hotel as his headquarters. In WWII the hotel was used as the German military HQ, which made it a target for Allied raids. By the end of the war, the hotel was a burned-out shell and the ladies’ section of the baths was completely wrecked (though fully restored, it is much less ornate than the former men’s thermal section—and today the baths are fully unisex).

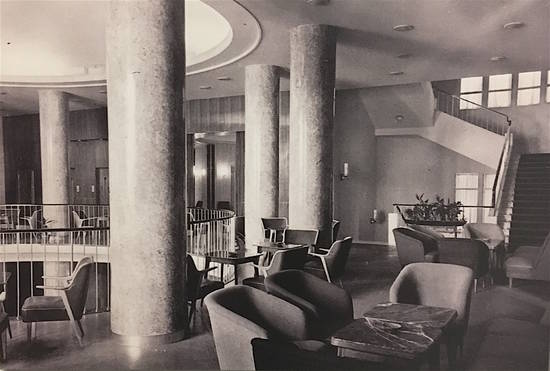

Plans to rebuild the hotel to modern, more Rationalist designs (drawings of these are on show) came to nothing and the exterior was restored more or less as it had been. It partly reopened in 1946. In 1948 came nationalisation, since when the hotel and baths ceased to operate as a single unit. Today the hotel is owned and run by the Danubius group while the Budapest municipality is in charge of the baths.

In its heyday the hotel rooms had all had hot and cold running water and in the suites, the bathrooms offered three types of water: municipal mains water, thermal water and carbonated water. The mineral content was found to corrode the pipes, however, and the practice was discontinued. Between the wars the hotel restaurant was run by the celebrated Gundel. On show are ice buckets, guest books, monogrammed crockery and menu cards, including that for a gala luncheon in 1933 at which Mussolini was the guest of honour. He ate eggs in aspic, chicken with salad and roast potatoes, and a chestnut cream slice.

Also on show are posters, pamphlets, souvenir keyrings and other knick-knacks, a restored neo-Baroque bedroom and some marvellous archive photographs, showing the hotel both as it was in the glamorous years before the Second World War, and as it became after the 1956 Revolution, when all the old furniture and fittings were thrown on the scrap heap and the interiors were remodelled in a brave new minimalist spirit.

Everything is excellently captioned and the wall texts are perfectly brief and informative. If you are in Budapest this winter—and especially if you plan to visit the Gellért Baths and/or are staying in the hotel, come and see this show.

“Gellért 100” runs at the MKVM in Budapest until 3rd March. Review by Annabel Barber, author of Blue Guide Budapest (which contains full coverage of both the MKVM and the Gellért Baths).