‘Some are born great, some achieve greatness and some have greatness thrust upon them.’ Shakespeare’s famous line from Twelfth Night might well ring in your ears as you go round this exhibition at the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest: Unsung Hero, an examination of the achievements and legacy of Arthur Görgei (1818–1916), military commander in Hungary’s 1848–9 War of Independence against Austria.

Görgei is an unknown figure outside Hungary. This is an important show not only because it introduces him to the wider world, but because of the way it confronts us with questions about the cruel and capricious nature of human hero-worship. We need heroes and we need villains, but we are curiously bad at deciding which is which. And then we treat our villains well and our heroes badly.

Görgei was not born great. Nor can it be said that he achieved greatness (though it briefly looked as if he might). Instead, he had greatness thrust upon him—but not until he had endured over four decades of bitter opprobrium, branded a traitor and vilified by the people he had served. How could this be?

Hungary is no stranger to the divisive figure, the character torn in two by opposing political camps. One generation will strew garlands on his grave, the next will lose their jobs if they dare to speak his name. This exhibition embodies such dichotomy in its use of repeated archways. The material is presented in sections, physically divided one from the other by a series of specially constructed arches which not only lead you forward, but also divide. The first one stands between two huge wall texts, both of them quotes from Lajos Kossuth, Governor President of revolutionary Hungary in 1849. In one, he hails Görgei as a loyal servant of liberty and predicts a glorious future for him. In the other he execrates the same Görgei as his country’s ‘cowardly and treacherous executioner’.

When one of Hungary’s greatest heroes (Kossuth) is so conflicted, what is the ordinary man on the street to think? The exhibition begins with some opinions of Görgei, solicited with no prior warning, from high-school students. Most of them turn out to be cautiously positive. A controversial figure. A great soldier. No one says he was a traitor. One (confusing him with someone else entirely) says, ‘There’s a portrait of him. Good-looking guy.’ (Wrong! Go to the back of the class!) Still, it raises an important point. What was Görgei like as a person?

He was born into modest circumstances, son of a Protestant family of good pedigree that had come down in the world through a mésalliance with a shopkeeper’s daughter. In a letter to his father, written when he was 14, the young Arthur expresses his ambition to be a soldier, a career which will allow him to serve his country and cater at the same time to his love of maths and physics. This idea of service was to remain a constant throughout his life.

We pass through another arch to find Görgei in military training school, his scientific ambitions temporarily abandoned. Lithographs, contemporary weapons and reconstructions of uniforms trace those years. Included is a uniform of the Palatine regiment of imperial hussars (the 12th), which Görgei joined in 1842 because the frogging on the jackets was of silver braid rather than the costlier gold. Another clue to the character of this austerely prudent Lutheran. In 1848 he was writing in Márczius Tizenötödike, periodical of the young radicals, pleading for more affordable uniforms for young officers, so that talented men of humble birth could progress according to their merits.

For ‘private and political reasons’ Görgei left the army in 1845. (NB: this exhibition is an audio-visual and kinaesthetic experience. You need to look at all the touch screens and open all the compartments otherwise you might miss something. The information about him leaving the army is tucked away in a drawer.) Beyond the next arch, we meet a Görgei who has backtracked to rediscover his scientific self. He remains in Prague, not as a soldier but as a student of chemistry, conducting research into fatty acids in coconuts. By all accounts he had a brilliant career ahead of him. But then, suddenly, he is offered the chance to return home, to manage the family estates of an aunt. To fit himself for this role he precipitately marries Adèle Aubouin, French governess in the household of his chemistry professor. There is no suggestion of a romance or even of tender feeling. Her memoirs are articulate on the subject: ‘His entire bearing was one of extreme modesty; and though the impression he created was a distinguished one, it was not immediately so. It was only after prolonged conversation, when one heard how intelligently he spoke—though his bright blue eyes, behind his glasses, were warm yet steely and his discourse filled with sardonic wit and sometimes surprisingly caustic remarks—it was only then that one became aware that this was a man of rare disctinction. During the whole course of our short acquaintance, he never paid his addresses to me…’

Görgei returned to Hungary with his bride in the spring of 1848 but he did not remain on his aunt’s estates. Revolution was in the air and he joined the Hungarian army. In one of his old military textbooks he has penned a note on the title page: ‘ “Arthur Görgey, Lietuenant” was my signature from the summer of 1837. Now it is “Görgei Arthur”.’ Görgei made this patriotic change in 1848, placing the surname before the first name in the Hungarian manner and substituting the aristocratic final ‘y’ with an egalitarian ‘i’. His progression up the ranks was astonishingly rapid. By the end of October Lajos Kossuth, in charge of the National Defence Committee, had made him a general and given him command of the Upper Danube army. It was a stellar rise in just five months. Görgei attributed his military success to the ‘mental discipline’ he had acquired as a scientific researcher.

Nowadays we might accuse Görgei of being a buttoned-up type, the kind of man who can’t emote. But he was capable of stirring language when it came to exhorting men to fight. Most of his words are abstract nouns and his favourite punctuation symbol is the exclamation mark: ‘Constitutional freedom! Honour! Glory! Forward, my comrades!’

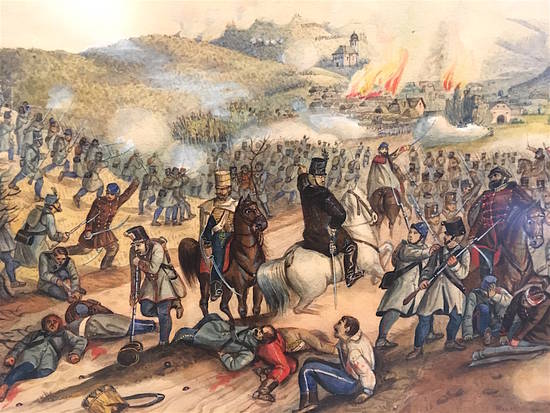

The next section takes us through the course of the battles. There is a huge model of the battlefields complete with tiny troops of men and horse, as well as some splendid watercolours of 1849 by Mór Than, who followed the army as a war artist while his brothers fought in the campaigns (he later went on to produce allegorical frescoes for the main stairway of the Hungarian National Museum building). One of the paintings, of the Battle of Isaszeg, shows Görgei in his glasses in the centre of the fray.

In early 1849 Görgei was put in general command of the Hungarian forces. In May he recaptured Buda Castle and in the same month was appointed Minister of War in the revolutionary government. As decisive victory continued to elude the Austrians, they called on Russian support and it was at this point that Kossuth began to question his relationship with the young soldier he had ‘raised from the dust’. In July, after disobeying Kossuth’s instructions, Görgei received a near-fatal head wound. The exhibited case of grisly surgical instruments and lead bullet containing fragments of impacted human bone make us wince to imagine the agony he must have been in. A later statuette of him on horseback (by the sculptor Barnabás Holló), his head bound in a kerchief like a Garibaldian guerrilla, focuses on the romance of the episode. Kossuth had no time for either compassion or romance. He waspishly opined that Görgei’s wits had been turned by all the schnaps he was drinking to dull the pain and in a letter of July 1849, written in his distinctive upwardly-sloping hand, he relieves Görgei of his army command.

By August it was all over. Kossuth resigned on the 11th and fled the country. Two days later, on August 13th, Görgei surrendered to the representative of the Russian Tsar. The Hungarian officers were executed. Only Görgei was pardoned, on the Tsar’s personal intervention. On show is a letter from the Austrian general Julius Jacob von Haynau informing him of this fact. His life was to be spared but he would live in internal exile near Klagenfurt.

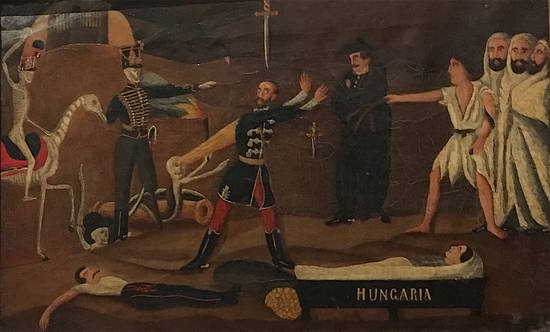

The accusations of treachery began from this point. In September, from the safety of Vidin, on the Danube in what was then Ottoman territory (modern Bulgaria), Kossuth wrote the vitriolic letter from which the first quotation in this exhibition comes: ‘Our sorry, wretched homeland has fallen. Not to the strength of our foes but to perfidy and treason…’. It had its effect and Görgei was hounded by public opinion. In October, after the execution of his fellow officers, the poet Vörösmarty joined his own voice to the clamour, calling down God’s eternal wrath upon the miserable wretch who so cravenly betrayed his country. Görgei’s steely blue gaze remains unwavering, his response phlegmatic. ‘If I were to take my own life I would enable my detractors to claim that I was driven to suicide by my guilty conscience. Therefore I have to live.

In exile, Görgei kept himself active. Charming watercolours by a daughter of a cloth manufacturer friend show him resolutely busy, hammering away in a carpentry workshop (perhaps following the example of an earlier Hungarian exile, Ferenc Rákóczi, who after his own failed rebellion occupied himself with woodwork beside the Sea of Marmara). Nevertheless, we should not be tempted to imagine Görgei as a lovable, wronged character. Always a fighter, he now showed himself happy to rush into print, firing off letters and articles. In 1852 he published his memoirs. Though available in London, New York and Turin, they were banned in Austria. And they were as merciless as might be expected from a man who seems to have seen parts of the world in such clear, close focus and the larger picture as a blur. Old comrades-in-arms loved it when Görgei excoriated their acquaintances. They were less pleased when he applied his scalpel to themselves. The caustic tongue and the stinging sarcasm that his wife had remarked on were key features of his approach. Not a way to make friends.

The Compromise agreement of 1867, which reconciled Hungary and Austria and ushered in the halcyon years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, brought amnesties and pardons, and at last Görgei was able to return to Hungary. He found what amounts to a series of odd jobs, never managing to settle at anything. Eventually he moved to Visegrád on the Danube Bend to manage the estate of his lawyer brother István, to whom he had always been close. (Rumours exist of a love triangle between Görgei, his brother and his brother’s wife, but the exhibition does no more than hint.)

In the 1880s, some of Görgei’s admirers began the task of attempting to clear his name. The efforts paid off, eventually. The exhibition ends with a small collection of personal artefacts and some charming photographs of Görgei as an old man, living in retirement and semi-obscurity, tending his garden. But he has his public side. The final arch takes us to the years of lionisation. Elder-statesmanlike and bewhiskered, he appears in dignified poses in official busts and portraits. All the great artists of the day—Stróbl, De László—seem to have lined up to portray him. There is a mini garland of sculpted metal sent him on his 90th birthday by the poet Andor Kozma: ‘May unfading laurels wreathe thy martyr’s crown of thorn.’ A journalist gushes in 1909 that ‘in his declining years the golden crown of truth is beginning to gleam upon his brow.’ Prime Minister István Tisza’s message of condolence on his death speaks of a misguided nation heaping odium upon a great man.

We get no sense that Görgei was any more dazzled by being fêted than he had been crushed by exile. It is true that he seems to have enjoyed reminiscing to a receptive audience—but who would not? And he still maintained that he had served his country, even by taking the name of traitor. For if Hungary had lost not through defeat but by treachery (as Kossuth claimed), then she had the excuse she needed to go on believing in herself.

Under Communism, though, it was back to black. Görgei was a counter-revolutionary, a traitor and a defender of the imperial officer class. Seeing this, it is difficult not to feel gloomily philosophical. We will always want our messiahs. Will always want our heroes to be whiter than white. We will never be able to cope with shades of grey. When given the choice, we will always vote raucously for Barabbas to be freed.

Görgei was an upright and unswerving person. Decent, principled and resilient. If necessary, ruthless and even unkind. He had no idea how to ingratiate himself with people who might otherwise do him harm, nor indeed any notion that it would be appropriate to try. You leave the exhibition the way you came, back past Kossuth’s two contradicting quotes. It’s a brilliant touch, because by the time you leave, you feel that Kossuth was not schizophrenic after all. Görgei wasn’t a traitor. But he was, and remained, Fortune’s fool.

His vision was weak (literally). Paintings around the time of the War of Independence show his eyes gleaming like milk-white moons behind his spectacles. Perhaps the clue to everything can be found in a single exhibited item: his cavalry officer’s sword with a lens attached to the hilt. It is a very strong lens. Viewed through it, the texts on the opposite wall appear tiny. How do things like this shape a personality? A study published in 2015 by Yıldırım Beyazıt University in Ankara, Turkey, found lower scores on ‘cooperativeness, empathy, helpfulness and compassion’ in participants with ‘refractive error’.

Historical events are not things bound to happen by the conjunction of the stars. Nor are they driven by men’s premeditated decisions. They are determined by a combination of design and hazard (or chance). The mixture of personalities plays a huge role. The encounter between Görgei and Kossuth was disastrous. One is tempted to resort to chemical metaphors involving insoluble substances and precipitation. Görgei would have known all about that.

In the end, probably, we get the heroes we deserve. Like all good exhibitions, this one provides some unexpected answers. It also poses some tough questions. If you are in Budapest, make time for it. Unsung Hero (Az ismeretlen Görgei) runs at the Hungarian National Museum until 23rd June.