“Matthias is dead—now books will be cheap in Europe!” Thus Lorenzo the Magnificent is said to have exclaimed on hearing of the passing of the King of Hungary, Matthias Corvinus, in 1490. Matthias , who became king aged 15 in 1458, can fairly be said to have led the way in exporting Renaissance art and humanism outside Italy. His erudition linked him closely with Lorenzo in Florence; in fact, the two exchanged letters about their progress in forming their libraries. That of Matthias, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was the first of its kind north of the Alps. Based on Italian models such as the library of Federico da Montefeltro in Urbino or of Ferdinand of Aragon in Naples, it came to contain around 2,000 precious volumes, mainly works by ancient authors and Church fathers, mostly in Latin, some in Greek. Only the Vatican Library could surpass it in scope and extent: Matthias is known to have lavished a fortune on the project, either acquiring existing manuscripts and incunabula or having exquisitely illuminated copies made. By paying so well, Matthias turned books into valuable commodities, and Lorenzo the Magnificent (who was putting together a library of volumes very similar in size and decoration to those of the Buda collection), may well have felt the pinch.

A superb small exhibition on Matthias’ library, with many items sourced from collections within Hungary as well as plenty from further afield—since the Buda shelves were emptied after the Ottoman conquest of 1541—is now on show at the National Széchényi Library in Budapest: “The Corvina Library and the Buda Workshop” (runs until 9th Feb).

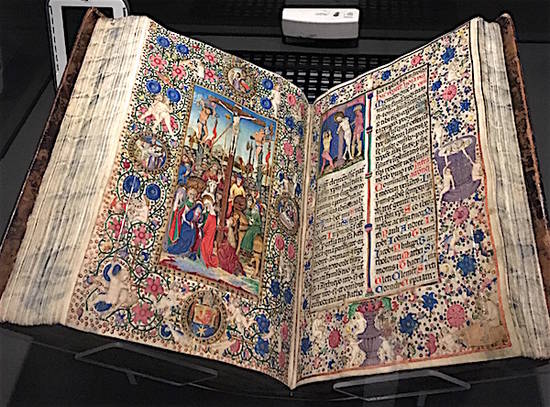

Matthias acquired his books from a number of sources. Many volumes were purchased from Italy; others he had copied and he set up a workshop for the purpose at Buda, under the direction of Italian illuminators. Matthias’ bride, Ferdinand of Aragon’s daughter Beatrice, also brought volumes with her from Naples: her coat of arms appears on a number of codices. From the 1480s Matthias began to give his collection matching leather and velvet bindings, with elaborately worked clasps.

Matthias appointed a librarian, Ugo Taddeo from Parma, to be in charge of acquiring existing volumes and commissioning copies. Our best contemporary source for what the Corvina Library may have been like is a four-part panegyric by the humanist poet Naldo Naldi. He tells of a vaulted room, tucked away in a secluded part of the palace, with coloured glass in the window apertures, incunabula and codices in inlaid shelves around the walls, their richly gilded bindings protected from dust by lozenge-patterned curtains. Between the windows stood a couch draped in cloth of gold, upon which the king would sprawl at his ease, supreme monarch among the Muses. Other seating was provided by three-legged stools upholstered in cloth of gold studded with precious stones (ouch!).

The artistic style adopted by the copyists in the Buda workshop was heterogeneous although broadly based on Italian models. Two of the leading hands were Francesco Rosselli from Florence and Francesco da Castello from Milan. The latter is known also to have been at work in Piacenza and for the Bishop of Lodi. The styles of these two men were generally regarded as the ones to follow but many of the illuminators at work in Buda were Flemish or German and the result is an interesting mix. The missal of a functionary at Matthias’ court, one Domonkos Kálmáncsehi, for example (1481, on loan from the Pierpont Morgan Library), contains only a single page illuminated by Francesco da Castello. The rest is by artists from Central Europe.

Another work thought to be by Francesco da Castello is the codex of Johannes Cassianus, concerning the rules of coenobite monks. Made in Buda (and on loan from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France), it has given its name to the “Cassianus” group of codices, all illuminated in roughly the same style, the border designs of acanthus fronds and grottesche appearing against red and blue backgrounds. The Cassianus codex was completed in the reign of Vladislas II, who succeeded Matthias after his death in 1490. Interestingly one of the volumes that presumably came to Buda with Queen Beatrice, a manuscript copy of Quintus Curtius Rufus’ Alexander the Great made in Naples in the 1470s, has a handwritten note on the flyleaf, perhaps written by Beatrice herself: “In the year of our Lord 1491, on the Sunday after Epiphany, I arrived here at Eger and on the third day also arrived the glorious King Vladislas who had been crowned in 1490 on the Sunday after the Exaltation of the Cross.” Beatrice managed to cling onto her position as Queen of Hungary by marrying Vladislas later that same year. But she gave him no children and so he rid himself of her by having Pope Alexander VI (the notorious Rodrigo Borgia) declare the union null and void. She returned to Naples—but whether she took any of her books back with her, I cannot say. Other books that remained unfinished at Matthias’ death have survived because they never came to Buda. There were over a hundred of these; many of them being worked on in Florence by artists directly employed by King Matthias. An example is the exquisite Bible, with illuminations by Attavante and the brothers Gherardo and Monte di Giovanni, which is today preserved in the Biblioteca Laurenziana.

Matthias’ library survived his death intact by only half a century. In 1541 the Ottomans took Buda and most of its treasures were scattered and pillaged. Near the end of this exhibition are two volumes that were returned to Hungary in the 19th century by sultans Abdülaziz and Abdülhamid. One of them, Caesar’s Gallic Wars (made in Florence in 1460–70), has had its original binding replaced by an Ottoman one with crescent moons. Another, St Augustine’s De Civitate Dei (made in Rome in the 1460s), preserves its 15th-century crimson velvet cover, with a gilt silver clasp decorated with the enamelled coat of arms of Matthias’ successor Vladislas, supported by twin dolphins.

This is a magnificent show; a rare glimpse into a world of luxury and learning. If you are in Budapest this winter, make sure to add it to your list.

Reviewed by Annabel Barber, author of Blue Guide Budapest.