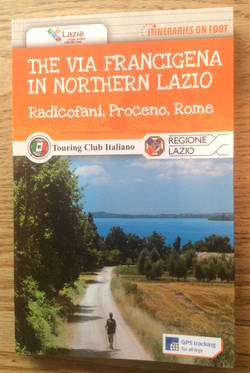

The Via Francigena in Northern Lazio. Map and guide in English from the Touring Club Italiano, Itineraries on Foot series. Reviewed by Charles Freeman.

The Via Francigena, the road of the Franks towards Rome, has been known for over a thousand years since Sigeric, the Archbishop of Canterbury, decided to travel to Rome for his formal investiture by pope John XV. The record of his journey in AD 990 lists each stopping place, 79 in all, and allows us to trace the route in detail. Sigeric crossed the Alps through the Great St Bernard’s Pass down into Aosta and then through what is now Piedmont into central Italy. As the flow of pilgrims increased and the route became used for trade and travel, cities such as Siena, hardly known in Roman times, grew rich on the proceeds.

The Touring Club Italiano has been working hard with Lazio Regional Council to open up the last 200km of the route. Much of the original, following the ancient Via Cassia, is now busy motorway and their recommended route is based on smaller roads and cart tracks that avoid noise and congestion but include all the original medieval sights that pilgrims will have seen. After a long first day from Radicofani to Acquapendente (30km) there are eight stretches of some 20km with hostels provided at each.

The guide is wonderfully thorough, with detailed maps of each leg of the route and blank pages for notes on each. The author, Alberto Conte, is sensitive to the beauties of the varied landscapes. If I ever take the route I shall be glad to know where there is a swimming pool close to the path and that the owner of the fruit stall in San Lorenzo Nuovo gives passing pilgrims a free piece of fruit. Original paved stretches of the Via Cassia appear from time to time. Thanks are still due to pope Gregory XIII who provided a bridge over the River Paglia in 1578, at a spot where sudden torrents had led to many pilgrims being drowned. There are tips on local wines and traditional dishes of the region alongside boxed sections on each of the major towns. It is useful to know that in September one cannot gather hazelnuts in the Torri d’Orlando as the farmers deliberately leave them on the ground before they are collected. It is tempting, as they are reputed to have the finest flavour in the world!

Yet it is the remnants of the churches, shrines and sanctuaries that grew up along the path that are probably most of interest. At Bolsena, in the 11th-century church of Santa Cristina, the footprints of the 4th-century martyr left on a rock can still be seen but it is the blood of Christ, spilling from a host onto the floor in 1263 after a priest doubted the miracle of Transubstantiation, that is the main attraction. The cathedral of Santa Margarita at Montefiascone, the city favoured as a residence by medieval popes, has the third largest dome in Italy after those of St Peter’s in Rome and the cathedral in Florence. In Viterbo the quarter of San Pellegrino, ‘the Holy Pilgrim’, still unchanged from medieval times, shows off the wealth accumulated from the flocks of pilgrims. Capranica, goat country, was a favourite haunt of the humanist Petrarch. One also passes close to the Etruscan city of Veii, of some nostalgia to me as I worked reassembling some of its domestic pottery at the British School in Rome back in 1966. And so finally into Rome, where the route ends in front of St Peter’s.

There were extensions of the Via Francigena south of Rome for those pilgrims who wished to continue to the East. These are shown on a large pull-out map in the pocket of the guide although the routes are not yet signposted on the ground. Overall this is a beautifully presented and thoughtful guide that will do much to open up forgotten treasures of Lazio. I have got as far as noting its checklist of what to take and wear on the road.

I am grateful to my old pupil, now Professore Simone Quilici, who is heavily involved in such projects, for giving me a copy of the guide when I last met him in Rome.