Talking to a friend a few weeks ago, he mentioned that he was about to go back to the Uffizi with a grandchild and would be showing him just five paintings there. A method of ensuring not only his full attention but also his appreciation. I can only imagine what a memorable occasion that will be for the child.

Returning myself to the gallery the other day, I took the lift up to the first floor, and on the stair landing, outside the entrance to the Prints and Drawings Room, a little room exhibits just one work owned by the Uffizi, (and it will be kept there until 30th April). This is a large triptych signed and dated 1461 by Nicolas Froment, a little-known artist from Picardy, much influenced by the Flemish school. It came to Italy because it was commissioned by Francesco Coppini, Bishop of Terni, probably while he was in Flanders. Born in Prato, Coppini had a distinguished early career as a lawyer and diplomat, and Leon Battista Alberti dedicated his De Iure to him in 1437. He was sent to northern Europe by Pope Pius II and when in England, as papal legate, he attempted to interfere in the War of the Roses. When he sided with Edward of York, who was crowned king in 1461, against the House of Lancaster, the pope promptly disowned him and he was defrocked when he returned to Rome.

Meanwhile the painting seems to have reached Pisa by 1465, but just what happened to it afterwards is not known: we next have news of it in the Franciscan monastery of Bosco ai Frati in the Mugello (apparently a gift from a Medici). When the monastery was suppressed by Napoleon it came to Florence, joining the Uffizi collection in the early 19th century, attributed to an anonymous German painter. It is only since 1878 that Froment has been identified as the French master of this triptych as well as that of the Burning Bush painted for René of Anjou in 1478 (and now in the cathedral of Aix-en-Provence).

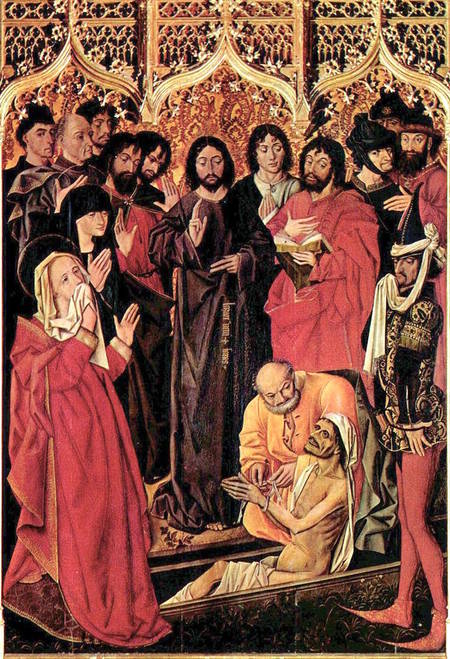

Today it has been wonderfully restored and is especially interesting for its subject matter, since it shows not just the central Raising of Lazarus, but also, on the left, the scene before the miracle, when Martha informs the Saviour that her brother is dead (the figure of Martha is the most memorable of all the figure studies in the painting) and, on the right, the Saviour seated at table after performing the miracle, having his feet anointed by Mary Magdalene. Lazarus (still with his beard and moustache, but now looking much better, dressed in blue) is sharing the meal. In this panel the fascinating details include a formal garden outside the window, and, on the table, a succulent roast chicken flavoured with herbs, a segment of pear with a fly settled on it, and a salt cellar. Judas (with a little fluffy dog at his feet) is the ugly disciple pointing at Mary, and Peter is the one cutting a slice from a loaf of bread by holding it and drawing his sharp knife towards himself (a gesture still sometimes to be seen at an Italian picnic). The central panel, with its lovely Gothic gilded fretwork, includes a self-portrait of the artist looking at us, and an amusing ‘courtier’ elaborately dressed trying to survive the stench coming from the decomposing body of Lazarus (who certainly looks as if he has indeed ‘returned from the dead’).

The triptych of three oak panels was made so that it could be closed, and on the panels of the door Coppini kneels before the Virgin.

On the wall of the room, a video illustrates details from the under-drawing, which was found through reflectography during restoration, and shows where the artist had second thoughts and altered his original design. The presentation is accompanied by an excellent little catalogue in Italian and English.

To learn about a painting’s history, and the technique used in producing it, apart from the name of the author and the subject matter, adds so much to its interest and increases one’s appreciation. It seems a very good idea to provide visitors with an in-depth study of one painting in this way, and hopefully it will encourage people to become more selective in what they choose to see among so many masterpieces in the gallery.

by Alta Macadam, author of Blue Guide Florence.