Hadrian is one of the most interesting and enigmatic of all the pagan emperors. He was a man of contrasts, described in the Historia Augustaas: “in the same person austere and genial, dignified and playful, dilatory and quick to act, niggardly and generous, deceitful and straightforward, cruel and merciful, and always in all things changeable.” He was a very cultured man, interested in art and architecture. Unlike his predecessor Trajan, his interest was not in extending the boundaries of his empire but in consolidating what he had, making sure that its borders held firm. But this does not mean he was inward-looking. The Roman civilisation spread peace through uniformity. All over their empire they built semi-identical cities, each with its temples, its baths, its forum, its theatre and amphitheatre, its circus, its mosaics of Dionysus and the Four Seasons, its public latrines. But Hadrian was not a conformist. He was exceptionally well-travelled and he was interested in the diversity of the peoples he ruled. His own architectural designs flouted the rules; they were almost baroque. In fact, the things that Hadrian admired most lay outside Rome, in Greece and Egypt. At his enormous, sprawling villa near Tivoli he created a little microcosm of his empire, with miniature versions of its beauty spots, from Athens to Thessaly to the Nile Delta to Asia Minor. Some of the statuary recovered from his recreation of the canal which linked Alexandria to the city of Canopus is displayed in the Vatican’s Egyptian Museum.

Bust of Antinoüs, Centrale Montemartini, Rome

Bust of Hadrian, Vatican Museums, Rome

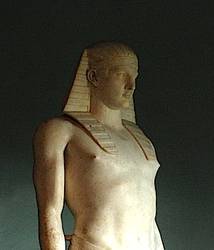

Hadrian built his Tivoli villa on land that belonged to his wife, the empress Sabina. Their marriage was loveless and childless. Though Hadrian deified his wife after her death, he must have known that she detested him. It is probable that Hadrian was homosexual. The image of his favourite, the beautiful Bithynian youth Antinoüs, haunts the museums of the world like a flitting ghost, portrayed in many a portrait bust or full-length statue, with drooping head, pouting lips and downcast eyes. Antinoüs died in mysterious circumstances, drowned in the Nile in ad 130, at the age of nineteen. Immediately the disconsolate emperor deified him and founded the city of Antinoöpolis on the river’s east bank. Many theories exist about this famous death: few believe that it was an accident. Perhaps the boy was getting beyond the age when it could be seemly for him to belong to Hadrian’s entourage. Or perhaps it was a ritual suicide. The cult of Antinoüs continued well beyond Hadrian’s day. The early Church fathers were in no two minds about it: Tertullian, Origen, St Athanasius and St Jerome are united in their opinion that Antinoüs was merely a man and that his worship was not worship, but idolatry—though they differ in how they express themselves. For St Athanasius, Antinoüs is a lascivious wretch. For Tertullian he is a hapless victim, a person who perhaps had little choice. From this distance, and with our utterly different social outlook, we can have no true idea. The Vatican Egyptian collection exhibits a statue of Antinoüs in the guise of the god of the underworld, Osiris, reborn from the Nile waters. It is a most extraordinary piece, offering a small glimpse into one of the ways in which people have attempted to make sense of death and immortality.

The Empress Sabina, Archaeologocial Museum of Ostia Antica

Antinoüs as Osiris, Vatican Museums, Rome