An extract from Pilgrim’s Rome: A Blue Guide Travel Monograph.

When you get off the train at Ostia Antica, you will do so together with a small huddle of visitors bound for the ruins of the ancient port city. Walk with them across the footbridge from the railway station, stick with them until you reach the main road of the little town; and then leave them: instead of turning left towards the excavations, turn right towards the castle and follow the road as it skirts around its moat. The church of Santa Aurea stands in the little cobbled Piazza della Rocca, a medieval village square with a medieval village atmosphere, surrounded by neat little cottages, supplied with a public drinking fountain, a restaurant in Via del Forno, and a church, all facing the massy protecting flank of the castle itself, built by Giuliano della Rovere, the future Pope Julius II, when he was bishop of Ostia in 1483–1503.

Behind the high altar a lamp has been placed upon a slender stump of column, balanced on a pretty fluted stand. These are certainly spolia from Ostia Antica itself, whose ruins lie somnolently basking under tall umbrella pines. As you make your way along the grass-grown basalt slabs of thedecumanus, you can easily imagine St Augustine and his mother doing the same, walking out to the shore through the Porta Marina, past the synagogue, to inquire about their boat to North Africa. We do not know exactly where they were staying, but we know that it was a house with a courtyard garden and there are plenty of surviving brick-built ruins that might have been it, some of them even with traces of an upper-floor balcony. In his Confessions, Augustine describes standing at a window with his mother, leaning out and chatting, speculating about the nature of the life beyond. Together they share a brief mystic moment when they seem to touch Eternal Wisdom. Two weeks later Monica was dead, of a sudden fever. Though her initial wish had been to be buried beside her husband, she maintained at the end that she had no fear of dying in a foreign land, for God would surely know where to find her when the Day of Judgement came. Very touchingly Augustine describes how he comes to terms with his grief, examining why he feels so bereft at the death of one who wished to leave this world and who has not, in any real sense, died. Psalm 101 was read over Monica’s body:

My song shall be of mercy and judgement: unto thee, O Lord, will I sing. O let me have understanding in the way of godliness.

Augustine returned from his mother’s graveside and went to the baths. We cannot know which baths those were; there are several that survive among the ruins of Ostia. Bathing did not soothe him. He retired to bed, wept freely, recited a hymn of St Ambrose (his mentor in Milan) and found himself much comforted.

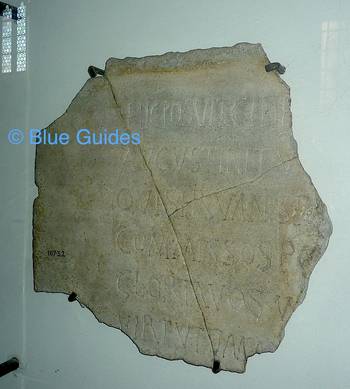

The church is small and very simple, aisleless, with a painted tie-beam ceiling and Stations of the Cross in bold white relief against a vivid blue ground placed high along the walls. In a chapel on the south side, behind glass, is a piece of the tombstone of St Monica, the mother of St Augustine, who died here suddenly in 387, aged fifty-five. Opposite the tombstone there is an Italian transcription of the full epitaph, which translates as follows:

‘Here your most chaste mother laid her ashes, Augustine, a further light upon your own merits, you, who as a faithful priest of the holy message of peace instruct by your life your faithful adherents. You are both crowned with immense glory by your works, you and your most virtuous mother, who is made more blessed still by her son.’

St Augustine’s own tribute to his mother is as follows:

May she rest in peace with her husband, her only one, after whom she married no other. She served him with patience and obedience, bringing forth fruit unto thee, and at the end won him also for thyself. O Lord my God, inspire thy servants my brethren, thy sons and my masters, whom I serve with voice and heart and pen, that whosoever of them shall read these words, may remember at thy altar Monica thy servant, with Patricius her husband, by whose bodies thou broughtest me into this life, though how it was done I know not. May they remember them in this failing light, they were my parents and also my brother and sister, subject to thee our Father in our Catholic mother the Church, and they will be my fellow citizens in that eternal Jerusalem for which thy people yearn all the days of their pilgrimage. (Confessions Book IX)

(NB: For a fascinating delve into early Christian Ostia, as well as for an alternative reading of Monica’s tombstone, see here.)