Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Until 15th February 2015.

This ambitious and extraordinarily ample exhibition will be the last of the Szépművészeti’s blockbuster shows, as the gallery is due to close in spring 2015 for large-scale refurbishment and reorganisation. The exhibition proudly presents works from the Szépművészeti’s own exceptionally rich 17th-century Dutch collection alongside loan works from the Rijksmuseum, the Metropolitan in New York, the National Gallery in London, the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, the Louvre, the Uffizi, the Getty and the Prado—to name only a few. “Over 170 works by some 100 painters”, we are told, and of those some 20 are Rembrandts and there are three Vermeers. A colossal show indeed.

How will order and sense be brought to this vastness? The scope of the exhibition is briefly set out at the beginning. Seventeenth-century Holland was a young country responding to great religious and social change as well as to inspiring, life-improving and sometimes disquieting scientific advances. Much of its art was commissioned by men who had made money from commerce. Thus new genres resulted: we can expect to see cityscapes, landscapes, scenes of civic and family life. Rembrandt is included as a sort of breakout display, alongside works by his master and pupils, for the sake of comparison.

The rise of Holland as a world power is dated to the time when the Dutch provinces, led by William of Orange, threw off Habsburg rule in the late 16th century. The very first work of art on show is a portrait of William (1579) hung alongside a naval battle scene showing an engagement between Dutch and Spanish galleys, then an allegory of peace followed by another of colonial power. With the scene thus summarily set, the themes of the succeeding rooms are as follows:

Faces of the Golden Age: The Building of a New Society

Wealth and Moderation?

The Influence of Protestantism on Religious Painting

Rembrandt and his Circle

Cities and Citizens

Landscapes

These themes are then illustrated, copiously. “Faces” shows us portraits of wealthy burghers, their wives and families. Members of a civic society are shown witnessing a dissection—though in fact they are all eagerly facing the viewer, just like any modern crowd jostling to be in the photograph. Members of another society are shown at a banquet. “Wealth and Moderation?” begins with still lifes (a lovely painting of tulips by Bosschaert) and domestic interiors (a superb Young Man Reading by Candlelight by Matthias Stom; 1620–32).

Later manifestations of both these genres show a moralising message creeping in. An old crone short-sightedly squinting at a coin, for example, becomes Sight or Avarice? A young girl looking at herself in a mirror becomes an Allegory of Profane Love. Pre-eminent here is Jan Steen’s In Luxury Beware (1663). A chaotic household is brought before us, dominated by a drunk and debauched young couple. Food and debris are all over the floor with a symbolic deck of spilled playing cards, the baby has got hold of a pearl necklace instead of its rattle, an untended fire blazes offstage right while the dog eats the remainder of dinner in the background on the left. The still lifes, too, become more sinister. Not merely celebrations of nature or of painterly virtuosity, they turn into allegories of the transience of life, of ephemeral luxury. Painting after painting (including Steen’s) includes the stock image of the half-peeled lemon, a symbol not only of passing time but a warning of bitterness below the surface. Snails invade the bouquets of flowers by Rachel Ruysch and Jan Davidsz de Heem.

“Religion” contrasts the paintings of the Utrecht school (the only city in Holland which retained a majority Catholic population) with stark depictions of image-free Protestant church interiors. The 20 Rembrandts are hung alongside his master Lastman and his pupils Flinck, Bol, Arent de Gelder, Hoogstraten (his wonderful, hyperrealist Letterboard one of the works on display) and Dou (master of the genre scene; his The Quacksalver of 1652 is a supreme example). “Cities and Citizens” gives us cityscapes (De Witte’s important c. 1680 interior of the Amsterdam synagogue) and urban domestic interiors, including Vermeer’s Astronomer and Geographer and some representative works by De Hooch, one of them expertly rendering the sunlight as it falls on a courtyard wall and another delicately capturing the effect of sunlight falling on the further wall of a room, reflected through the panes of a window opposite.

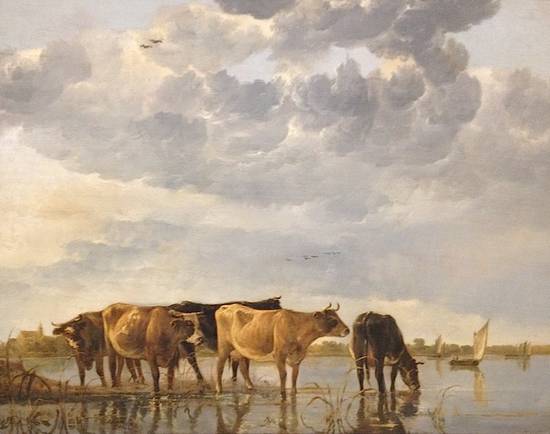

The last room, “Landscapes”, has some splendid works by Hobbema, Avercamp, Cuyp, Ruisdael, Wouwerman and Berchem. “But this is a terribly big exhibition!” one lady protested to another as she steeled herself to tackle it, “It’s impossible to take it all in!” Sadly, she’s right. There is too much to see. Partly the problem is that there is nowhere to sit and admire any of the works (except for two stools in the De Hooch room). Partly that the physical division of the exhibition spaces does not correspond to the thematic division of the exhibition itself, which is confusing. You pass through a partition which leads you to assume that you are done with “Cities and Citizens”, for example, only to discover that this is not the case. There are still two more sections to go.

The visitor is left with the problem of how to digest an over-ample meal, of the kind that leaves you replete but stupefied. Less would be more. A couple of choice still lifes; a single moralising genre scene. And if we had had fewer still lifes and genre scenes to work through, it would have been easier to notice (they are several rooms apart) that Stom’s Young Man Reading is as Caravaggist if not more so that Terbruggen’s Calling of Matthew. Stom was also from Utrecht. He spent most of his career in Italy. Thematically his work belongs where it has been placed; temperamentally it does not. The “Influence of Protestantism on Religious Painting” is one thing but what we see here, and what 17th-century Dutch painting so wonderfully illustrates, is the influence of Protestantism on ALL painting. With images banished from churches, the wealthy began to commission not altarpieces of their patron saints but portraits of their own selves. A still life with a skull and candle can serve just as well for personal devotion if there is no longer the opportunity to endow one’s local church with an expensive St Jerome in the Desert.

And how did the artists themselves fare? In Rome a landscapist like Claude could find favour with popes and cardinals. Was there a similar network of protection and patronage in Holland? Still lifes commanded less money than a genre scene, less by far than a vast canvas of scrubbed and beaming members of a city guild crowded around a banqueting table, each face a portrait from life, the whole to go on public display. Such a work could make a painter’s name and fortune. But the exhibition does not deal with this aspect of the subject.

It does, though, show us some wonderful paintings. Here are a few more of them:

A lovely example of the Vanitas school of still life painting, showing the abundance of nature and the things money can provide while at the same time hinting at transience and decay. Oysters are swift to putrefy; the snail will devour the flowers; the butterflies are but fleeting flashes of pied beauty (or allegories of the soul?); the taper (seen glowing in the far left of the crop) marks the passage of time; the earwig hastens corruption; the china bowl is an epitome of fragile beauty.

The setting is a “house chapel”, a room in a private home where Catholics were permitted to worship (public worship in churches was forbidden to them). A rich curtain patterned with a secular scene of a horseman and fruit, normally drawn across the chapel to screen it, is pulled back to reveal an altar on which are placed a chalice, crucifix and Bible. The backdrop is a large-scale painting of the Crucifixion. Beside the altar sits the personification of Faith, her foot upon a terrestrial globe, clutching her heart in ecstasy as she contemplates the pure sphere of Heaven symbolised by the crystal ball suspended from the ceiling by a ribbon of bright blue, the symbolic colour of the spirit, matching Faith’s shawl. On the floor is a snake, crushed and bloody, its life knocked out of it by the heavy masonry block, a symbol of Christ the cornerstone (as he is described in St Paul’s letter to the Ephesians).

The Dordrecht painter at his very best.

And what of Rembrandt? Many of his works in this exhibition are early paintings, including a wonderful stock character study of a turbanned man (1627–8), the gold threads in his white headdress glisteningly picked out, the face half in deep shadow. Also here is his splendid penitent St Peter (1631), toothless and full of remorse in a Roman prison, his heavenly keys cast uselessly aside on a heap of stinking straw. Rembrandt seems much less at home in the Classical world (his stout Minerva and his Cupid with a Soap Bubble are two examples of a genre to which his genius was ill suited). Much more successful is his The Kitchen Maid, a scene of life as it is lived, without symbolism or allegory. This is art for art’s sake; the meaning is what the viewer finds in it.

Rembrandt’s famous self-portrait of 1640 is also here (on loan from the National Gallery in London), the image of an artist at the peak of his career and fame, confidently signed with his name writ large at the bottom. Contrast this with his much later self-portrait (late 1660s; on loan from the Uffizi). The eyes, like those of the Laughing Cavalier, follow you wherever you turn, but not with a merry gleam. Instead they fix you with an unsettling, almost cynical scrutiny. What went wrong in Rembrandt’s life and career? This exhibition is not going to tell us. For that, we have to turn to the show of his late works currently running at the National Gallery in London.