At the Royal Academy, London until 25th January.

For anyone who loves Lombardy, Giovanni Battista Moroni (1520/4–1579/80) will be a familiar name. He is one of the finest portraitists of 16th-century Italy. This small and beautifully curated show at the Royal Academy attempts to demonstrate that he can stand with the finest portraitists of any time or place.

Moroni’s reputation outside his native Lombardy suffered from the fact that he never left it, except for visits to Trento at the time of the famous ecumenical council. The city of Bergamo, in whose district he was born, was a part of the Republic of Venice. But Moroni never went there, as others did, to become a star in its serene firmament. He stayed at home and painted portraits of local nobles and tradesmen, altarpieces for local churches, and panels for the personal devotion of local patrons. He was famous and much appreciated in his lifetime, but faded from view thereafter—at least, outside his homeland. The blame for this is traditionally laid at the door Vasari, whose Lives of the Artists does not mention him. And yet Moroni was only producing his best work around the time that the expanded edition of the Lives was published, in 1568. And when Vasari travelled to northern Italy in search of material in 1566, he did not visit Bergamo, or Albino, the little town to its northeast where Moroni was born and to which he returned to work in his later years.

Vasari does however mention Moroni’s master, Moretto da Brescia. He was “a delicate colourist and of great diligence,” we are told, “fond of imitating cloths of gold and silver, velvet, damask and other kinds.” The exhibition opens with a selection of his works: some portraits and an altarpiece. His portrait of the haughty young Count Martinengo (from the Museo Lechi in Montechari) shows the technique that his pupil Moroni would adopt with such success: a three-quarters tilt to the head, eyes fixing the viewer, the sitter’s face the focus of the artist’s efforts, background elements at a minimum (though you will start to recognise some studio props: the gloves, the chair, the leather-bound book). The best portraits are not showpieces of wealth and consequence. They are likenesses—psychological studies—of ordinary human beings. That, to our modern eye at least, is what is most absorbing.

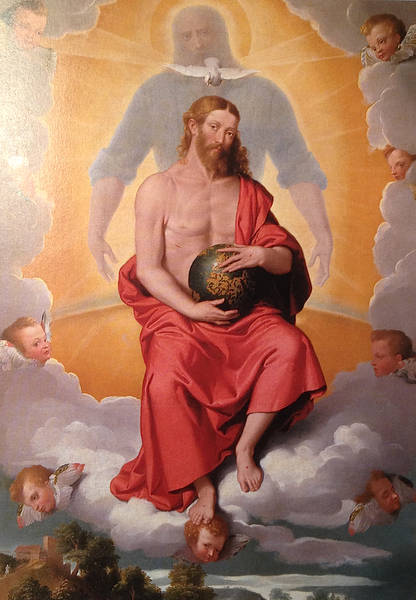

And indeed, they keep the viewer riveted. The show was crowded when I went, and visitors were stuck fast in front of the portraits, audioguides clamped to their heads, whispering to each other in rapt admiration. The altarpieces commanded far less attention. This is not necessarily fair, because if Moroni’s sacred subjects fail, they fail for a reason. The Council of Trent, which abjured the Protestant Reformation, called for a return to the precepts of the past, an establishment of rules and method, a forsaking of invention and novel interpretation. Later it was to shake itself free and find its own Counter-Reformation style, the sensual, ecstatic, exuberant Baroque, charged with a direct emotional appeal. But this had not happened yet. Painters of religious subjects in Moroni’s day were rigidly stuck with old themes and old poses, not wanting to be archaic but unsure how to be modern. This predicament is brilliantly illustrated by two large-scale altarpieces of the Trinity, the first by Lorenzo Lotto (1519/21; Museo Bernareggi, Bergamo) and the other by Moroni (c. 1552; church of S. Giuliano, Albino). Both show pale clouds parting to reveal the primrose-yellow dazzle of Heaven. Christ appears in the centre, upon a rainbow, with the dove of the Holy Spirit above his head. Behind him, in looming shadow, is God the Father. But in Lotto’s version God appears in shadow only, as a suggestion of immanent power, hands upraised. In Moroni’s Trinity, God has been humanized. He has a face, a blue robe. His arms encircle Christ in a gesture of protection. But the overall effect is stilted, bizarre. The rolled up sleeves make him look like a strongman about to perform a feat of heavy lifting. “Is that supposed to be God?” someone asked incredulously, “You don’t normally see pictures of God, do you?” “Of course you do,” his wife testily reproved him, “Michelangelo did one.” Yes, Michelangelo did, in sophisticated, neo-pagan Rome on the Sistine ceiling. A God looking like an ancient Zeus touching fingers with Adam in the guise of a body-perfect ephebe. But that was Rome and that was then. This is Lombardy. One cannot do portraits of God.

Portraits of men and women, on the other hand, are another matter. Nowhere is this dichotomy better revealed than in Moroni’s sensational Last Supper (1566–9), painted for the Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament in Romano di Lombardia, where the faces of Christ and his disciples are stock character heads, in sharp contrast to the man standing at the back. An intruder into the scene, he plays the role of host or servitor at the supper party, holding a flagon of wine in his hand and looking us straight in the eye. This is a portrait of a real person; perhaps, it is thought, the parish priest of the little town. The dimension he inhabits is perceptibly different from that of the staged actors in the famous dinner drama, who are all playing prescribed parts and have no existence beyond them.

Moroni, like his master before him, was fond of painting fabrics. What Vasari does not tell us is that Moretto painted the first ever Italian full-length portrait, in 1526 (London’s National Gallery has it). His pupil borrowed both the full-length and the three-quarter-length style and took them to new heights. There are some superb portraits in this exhibition, shown to dazzling effect in the third room, where nine works have carefully been chosen to complement each other to perfection. Two seated ladies (opposite each other), three full-length men (opposite each other and opposite the door) and four three-quarter-length men are hung with careful attention paid to which direction their gazes face. Yet the hang is both complementary and antagonistic. The two women, both poetesses, were from opposing factions in the Bergamo of the day, the bloodily feuding Albani and Brembati families. The Brembati belonged to the imperial, pro-Spanish faction: the striking Man in Pink, Gian Gerolamo Grumelli (from Palazzo Moroni in Bergamo, the home of the artist’s descendants), was the husband of Isotta Brembati (the second of the poetesses). It is signed and dated “Jo. Bap. Moronus p. MDLX” and features a Spanish motto: “Mas el çaguero que el primero” (Better to hang back than to rush to the front; an admonition to prudence?). Behind the sitter is a ruined wall. Damaged masonry over which ivy creeps and into which weeds intrude—and beyond which blue sky and cirrus clouds can be seen—is a favourite Moroni backdrop. It occurs in five of the nine portraits in this room and again in the final room. The architectural background with blue sky behind was used by Moretto in his first full-length. Again, Moroni adopts, adapts and carries forward: the warning of ruin and decay, it seems, was his idea.

In the final room we come face to face with Moroni’s famous Tailor (c. 1570; National Gallery, London), and other mature works which show, in the curators’ judgement, his role as a foreshadower of Manet and Ingres. The Tailor shows a finely-dressed young man in fashionable slashed pantaloons, looking up from his worktable where he was about to cut a length of black cloth. Black, the exhibition catalogue notes, became the favoured colour for men’s costumes, replacing the sumptuously coloured stuffs of earlier years. The tailor himself is obviously a successful artisan. Tailors, according to the wall caption, often dressed well—perhaps as a way of making themselves walking advertisements for their trade. But it was not the tailor’s eyes that stayed with me, as I walked out onto a rain-washed Piccadilly. It was those of the Lady in Black, whose portrait (c. 1570; Palazzo Moroni, Bergamo) is a model of minimalism and a seeming effortless skill at capturing not just a likeness but a personality.

Go and see this show if you can. The ticket price is not cheap (£12) but I think you will feel it was worth it.

Reviewed by Annabel Barber. The Royal Academy, its history, role and exhibitions, as well as the architecture of its home, Burlington House, are all described in detail in Blue Guide London.