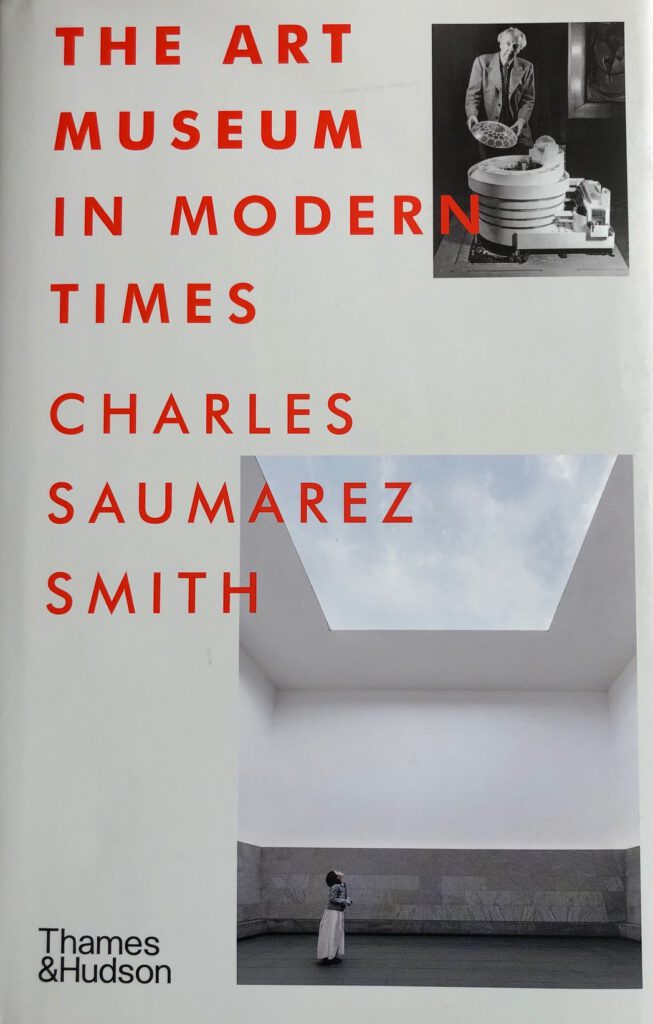

This new book by Charles Saumarez Smith (Thames & Hudson, 2021) is a fascinating look at how museums, their mission and their vision, have evolved over the past half-century. Forty-two museums are explored; the choice is personal, focusing on institutions that the author knows well, without any aim to be deliberately exclusive. Saumarez Smith joined the staff of the V&A in 1992. Throughout the course of a distinguished career, he has been director of both the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery, and Secretary and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy, all in London.

As he was writing the book, Saumarez Smith noticed a clear pattern: a ‘universal decline in belief in a master narrative.’ In its place, he detected ‘a growing interest in the validity of individual response…and in treating the museum as an opportunity for private adventure.’ In an age when Tate thinks Wikipedia can give just as good a summary of the life and work of the artists represented in their collection as their own curators could or should, this study is more than timely.

Museum directors were once upon a time supremely imperious. The director of the V&A in the early 1930s described the public as ‘a noun of three letters beginning with A and ending with S…We heave sighs of relief when they go away and leave us to our jobs.’ For him, the visitor off the street was an unwelcome nuisance, not the raison d’être of his institution. Museum directors might still be imperious, but so are donors and trustees—and so are artists and architects. Lina Bo Bardi, who designed the MASP in São Paulo (opened 1969), is quoted as declaring: ‘The museum belongs to the people…They gaze at a picture in the same way they look into a shop window…They take part even if they lack “cultural grounding”.’ Far from being in the way, the visitor off the street has become fetishised. The museum and its designers take their cue from him or her and try to appease his/her appetites.

The idea that ‘museums and galleries should be places of deep scholarship more than public enjoyment’ has gone. And it is interesting to see how museum design reflects this. Firstly, there is the building. Up until the outbreak of WWII, the accepted architectural style for a museum was Neoclassical, a temple to the Muses. As an example, Saumarez Smith gives the National Gallery of Art in Washington, designed in 1937. With its colonnaded portico, its central rotunda modelled on the Pantheon in Rome, and its gallery spaces arranged around a courtyard, it was designed to be stately and solemn and to serve the art it housed.

Two decades later, the construction of the Guggenheim in New York brought to the fore a tension between curators, who wanted spaces to exhibit art, and architects, who wanted those spaces themselves to steal the show. The Guggenheim’s architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, was seen to have won the contest when almost three thousand people queued up to get inside his building when it opened in 1959. Ever since then, people have regarded the Guggenheim Museum as ‘a great symbolic monument, at least as important for the experience of its architecture as for seeing its collections.’ Another architect who liked to call the shots, Mies van der Rohe, said airily of his Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin (1968): ‘It is such a huge hall that of course it means great difficulties for the exhibiting of art. I am fully aware of that. But it has such potential that I simply cannot take those difficulties into account.’ And this concept, of the museum building not simply as a receptacle for knowledge or revelation but as an iconic piece of starchitecture, has been tenacious. A later Guggenheim Museum, the one in Bilbao by Frank Gehry (1997), represents what Saumarez Smith believes is a paradigm shift: ‘No one thinks of it in terms of its collection.’ It is famous as a monument in its own right, like the Taj Mahal. People go to visit it for its own sake, to experience the excitement of its architectural form.

I.M. Pei (National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1978) celebrates the fact that ‘Museums have become much more than storehouses for art; they have become also important places for public gathering.’ The museum’s role is to provide visitors with a special sort of experience, beyond what everyday life can provide, and the emphasis is no longer on learning but on individual response. So it is not only the architect who holds the reins; it is also the public. The Victorians regarded themselves as public-spirited, as educators, as throwing open doors to a wider populace. Now, though, we see their attitude as de haut en bas. We see their grandiose buildings not as thrilling and inspiring but as intimidating; we see their egalitarian educational ideal as elitist; we see as blinkered their belief that focusing attention on the objects on display would open windows in the mind. Saumarez Smith himself directly tackled this in the Ondaatje Wing of the National Portrait Gallery in London (2000): ‘A coolly democratic attempt to open up and widen public access to a Victorian public institution…and to make it look outwards by giving it a view from the restaurant over the rooftops.’

With the desire to make the public feel embraced rather than instructed, art loses its pole position. Nicholas Serota describes Tate Modern (London, 2000) as ‘a place that people will want to go and meet others and then perhaps go and look at some modern and contemporary art. It’s a place that should become part of the social fabric as well as the cultural fabric.’ In the 19th century this function was provided not by the museum but by the village church or opera house, where people went to catch an eligible eye rather than pay attention to sermons or soprano solos. But today, it is not only the design of museum buildings which has shifted, it is also the curatorial approach. At the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas (Renzo Piano, 1987), the walls were kept free of explanatory texts so that nothing could ‘interfere with the emotion art could inspire in the viewer.’ Deep knowledge, which a traditional curator might have thought necessary before the public can fully understand and appreciate the art on display, has become an encumbrance. Instead people go to explore themselves. Again discussing Tate Modern, Serota says, ‘Our aim must be to generate a condition in which visitors can experience a sense of discovery…rather than find themselves standing on a conveyor belt of history.’ It now seems axiomatic that historical narrative is bad, that fixing individual works of art in historical relationships to other works of art is too preachy, too systematic, too objective. Peter Zumthor, architect of the Kolumba diocesan museum in Cologne (2007), talks of works of art being treated as ‘objects to be contemplated and appreciated aesthetically and spiritually without too much explanation or an imposed historical interpretation. The point is to look, to think, to contemplate, and to absorb their beauty.’ Instead of the works, via the medium of the museum, transmitting inherent meaning to the viewer, the viewer is invited to bring his or her own meaning to the works and to be somehow redeemed by them.

The design of the Benesse House Museum in Naoshima (1992) was informed by ‘a belief that museums could provide access to a different order of quasi-spiritual experience from the everyday consumer world.’ At Renzo Piano’s Beyeler Foundation in Basel (1997), people use its spaces for ‘reflection and contemplation—spiritual recuperation.’ But alongside contemplation and response, museums have also come to be about adventure. Architects have been keen to make their spaces mysterious. Instead of the progression through a clear enfilade we have the maze. ‘Mystery has replaced logic. Order and rationality have been displaced by unpredictability.’ This is the museum as funfair, ghost train, escape room. Parts of it might be given over to retreat and contemplation; other parts are for social mingling; still others for fun or for commerce. It is a city within a city and as such, the museum has given itself an ambitious role; it has ‘increasingly important public responsibilities beyond the simple display of art.’ But when museums start thinking in terms of public responsibilities, is this not arrogating authority to themselves? And how does one avoid the danger of institutionalisation? The new MoMA (2004) designed by Yoshio Taniguchi, is, Saumarez Smith thinks, ‘too bland, too like a corporate headquarters for modern art.’ So on the one hand there is the risk of corporate vanilla; on the other, a danger of turning art galleries into retail spaces. ‘Museums are becoming ever more commercial and looking ever more like shopping malls.’ An ephemeral quality is becoming more apparent, too. Major Western museums are starting to franchise their collections in other parts of the world—China, the Gulf—but while governments are keen on financing totemic buildings, paying for high-quality staff and long-term running costs is another matter. Perhaps a museum might have no permanent collection at all but simply be a pop-up, borrowing iconic works for a limited period, used as a tool of soft power.

For much of the second half of the last century, pedagogues would talk about language ‘acquisition’ as opposed to language ‘learning’, convinced that acquiring language naturally, as a child does, instead of memorising cases and declensions, was more communicative and more fun. For most of that same half-century, museums have stopped being ‘places where visitors come to find out, and be told, about the past: they are no longer treated as public lecture rooms, where works of art are laid out according to strict historical sequence.’ But grammar can be a democratic and liberating tool and it can level the playing field. Can art history not do the same? And if curators believe in a definite message and in an imperative to transmit it, will the schoolroom approach not have to make a comeback? It might be that we are at just such a juncture now. In Lens in northeast France, at the satellite Louvre museum by SANAA (2012), the part of the project which Saumarez Smith found most successful and memorable is the Galerie du Temps, ‘laid out as a walk through a three-dimensional, transnational history in which some of the greatest objects from the Louvre’s collection are presented laterally along a strict timeline…It is exceptionally logical and intellectually coherent; possibly oversimplified, but all the better for being so easily understood and properly transnational—indeed, as far as possible, global.’ In 2012, the agenda was not the same as it would have been in Victorian times, when global and transnational were not buzz-words, but the curators have a new message and they have reached back to the logical, intellectual, historical approach to convey it.

This superb and eminently readable book takes us along a roller coaster of ups and downs, experienced by museums as they lose, regain, refashion their intellectual confidence, their belief in or rejection of, the notion of a set of universal values, alternately giving prompts to, or taking their cues from, the public. Are we a temple or a shopping mall? A schoolroom or a playground? A set-menu restaurant or a smorgasbord? At the back of our minds we know that our conclusions, half a century of ‘experiments in trying to relate the experience of art to the public’, might seem hopelessly wrong-headed by the generations that come next. But that is natural and museums ‘will continue to be rethought, redesigned and redisplayed as a result of new beliefs about their purpose.’ The 19th-century museum founders, with their mission to educate, believed that by studying the past we could learn about our present selves and the progress our civilization had made. Today, in an age which is at once self-flagellating and narcissistic, we are less interested in our past, but the mission to direct people’s thinking and to cultivate their responses is alive and kicking.

Saumarez Smith ends on a slightly sombre note. He is not sure that museums will regain their moral confidence or their financial security. There are also, with collections sourced from around the globe, inevitable questions of legitimate provenance and restitution. He concludes too, that after the death of George Floyd, museums failed to pay attention to public concerns, that they did not find a systematic way to respond to the legacy of slavery. Might a moral certainty about the need for a certain way of thinking return in the light of this? Might we see, after all, the resurgence of the didactic approach, with carefully thought-out explanatory labels unequivocally telling us what’s what?

Reviewed by Annabel Barber