In the Roman province of Pannonia, most veterans who received donations of land settled down to a life of animal husbandry and crop-growing, living well, perhaps, but modestly. There was at least one villa, however, in the centre of a 20-acre estate, that had pretensions. It lay close to the main road to Aquincum, which branched off the Amber road between Aquileia and the Baltic. It flourished in the third century AD and its owners were obviously familiar with grand villas in Italy, for they chose to imitate them in the style of opulent floor mosaics and in the wall paintings. The Pannonian climate was harsh and the peristyle garden was walled in, with engaged rather than free-standing columns (top picture), but still the decoration, with its trompe l’oeil fence, with painted trees and flowers behind, sought to give the impression of a real garden and brings to mind the fine decoration of the Villa of Livia near Rome. Sculpture was crude (see the head of Hercules, middle picture) with his tight curls looking like a tortoiseshell helmet) but the mosaic work was superb, as the floor of this apsidal hall attests (bottom picture). The family buried its members (including a horse and a dog) in a grand mausoleum on top of a nearby hill. By the fourth century, all was over. The villa began to fall into ruin.

Monthly Archives: August 2012

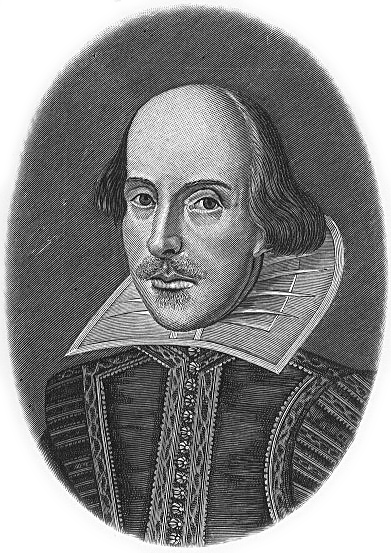

The Bard of….Messina? Was Shakespeare Sicilian?

A few years ago, Martino Juvara, a retired schoolteacher from Ispica in the province of Ragusa, presented the theory that William Shakespeare had nothing to do with Stratford-upon-Avon but was in fact born in 1564 in Messina, Sicily, and given the name Guglielmo Crollalanza (’Falling Spear’). When still a boy, because of his father’s Calvinist leanings, the family was forced to flee to Verona, where they had relatives. Here the young Guglielmo stayed in a house belonging to a certain Othello (where a certain Desdemona had been killed), fell in love with a certain Juliet (who later committed suicide), and a few years later went on to England, where he changed his name to William Shakespeare to facilitate his acceptance into the new country. Juvara’s theory is largely based on a series of coincidences. Shakespeare mentions Sicily in five of his plays: Julius Caesar, Much Ado About Nothing, Antony and Cleopatra, A Comedy of Errors and A Winter’s Tale. His rich vocabulary would indicate a good knowledge of Italian, and he used many Sicilian proverbs in his works: ‘much ado about nothing’, for example, is a translation of the old proverbtantu schifiu ppi nenti, and ‘all’s well that ends well’ is si chiuriu ‘na porta e s’apriu un purticatu. What’s more, some of his biographers say Shakespeare had a foreign accent–though for a good actor that wouldn’t have been difficult to assume, if he wanted to give himself exotic appeal. So far, perhaps not surprisingly, this new idea about Shakespeare’s identity has met with widespread scepticism….

The 8th edition of Ellen Grady’s Blue Guide Sicily is out now.

Rereading Ruskin

by Alta Macadam

As I begin a revision of the Blue Guide Venice for a ninth edition to be published next year, my thoughts have turned to Ruskin and all he taught subsequent generations about the way to look at the city. I have always been fascinated by his detailed descriptions in The Stones of Venice and the picture of him at the very top of a ladder propped against one of the columns of the Palazzo Ducale to peer at close range at the carvings on the capitals in order to scrutinize their every detail and be able to describe the expressions of the figures, the texture of the stone, the very spirit of the work of art. But it was his autobiography, Praeterita (1899), that I have recently reread with particular pleasure.

Here his very earliest memories as a four-year old during his idyllic childhood in his simple home with its orchard at Herne Hill are memorable. His father was a wine- merchant and in the summer months John and his mother would accompany him by carriage throughout Britain on visits to his clients. He recognizes that his parents over-indulged him and he made sure their ambitions for him to become no less than a bishop were foiled. His fond descriptions of the people whom he most admired, including his Croydon aunt, children of his own age, as well as his nurse Anne (“she had a very creditable and republican aversion to doing immediately, or in set terms, as she was bid”), reveal his generous spirit and insight into character.

Later in the book he describes at some length how he delighted in making detailed sketches of the places and things he saw throughout his life. According to Kenneth Clarke (in 1948) these include “some of the most beautiful architectural drawings ever executed”. Ruskin also gives us a delightful account of his writing method: “My own literary work…was always done as quietly and methodically as a piece of tapestry. I knew exactly what I had got to say, put the words firmly in their places like so many stitches, hemmed the edges of chapters round with what seemed to me graceful flourishes, touched them finally with my cunningest points of colour, and read the work to papa and mamma at breakfast next morning, as a girl shows her sampler”. A simplistic description of how some of the great prose in the English language was constructed. It is difficult to detect that the period in which he was writing these memoirs was clouded with terrible bouts of depression, which his contemporaries were quick to put down to fits of madness.

When at last, about half way through Volume I, the family decide they must go and see for themselves the wonders of the Continent, Ruskin notes just how much things had changed since then: “The poor modern slaves and simpletons who let themselves be dragged like cattle, or felled timber, through the countries they imagine themselves visiting, can have no conception whatever of the complex joys, and ingenious hopes, connected with the choice and arrangement of the travelling carriage in old times”. And of course we realize how far removed we are now from his time and are fascinated by the details of the carriage which was to be virtually their home for the next six months or so, led by four “properly stout trotting cart-horses” who, with a change at each post-house, were able to take them some 90 miles a day. We are given a description of the postillion as well as the courier: “A private Murray who knew, if he had any wit, not the things to be seen only, but those you would yourself best like to see”. Ruskin remembers the “luxury and felicity” of never being in a hurry, in contrast to the “modern” tourists who were travelling by train at the time he was writing his memoirs.

Much of the description of his travels with his doting parents is concentrated on France and the sublime Alpine scenery of Switzerland—“the revelation of the beauty of the earth”—although he is perceptive enough to understand that “the temperament belonged to the age” and a child born a hundred years earlier, or (we may add), a hundred years later, would not have been carried away as he was by his first distant view of the mountains from Lake Geneva. But we are also given some wonderful passages about Venice. He remembers that he knew the city before ever setting foot there through the art of Turner (he and his father delighted in purchasing many of his works), and the writings of his master Byron: “here at last I had found a man who spoke only of what he had seen, and known: and spoke without exaggeration, without mystery”…“he bade me seek first in Venice—the ruined homes of Foscari and Falier”…“Byron told me of, and reanimated for me, the real people whose feet had worn the marble I trod on”.

In Volume II when finally he arrived in Venice he experienced “the pure childish pleasure in seeing boats float in clear water. The beginning of everything was in seeing the gondola-beak come actually inside the door at Danieli’s, when the tide was up, and the water two feet deep at the foot of the stairs; and then, all along the canal sides, actual marble walls rising out of the salt sea, with hosts of little brown crabs on them, and Titians inside”…“Thank God I am here; it is the Paradise of Cities”.

Ruskin remembers fondly the days he spent in his gondola: early in the morning moored among the boats at the busy Rialto markets and then in the afternoon fastening a rope to a fishing boat to be pulled out to the Lido as he sat sketching the wind in the sails, or the view back of Venice shining beyond its islands. He tells of hours spent in the Scuola di San Rocco among the Tintorettos—the painter he most admired there and whom he considered had been totally neglected by the English public up until then. He speaks with great affection of two Englishmen he met on his travels, Rawdon Brown in Venice, and Joseph Severn in Rome, pointing out their generous spirits with unaffected admiration.

In Volume III he treats us to the most delightful description of his dog Wisie (“exactly like Carpaccio’s dog in the picture of St. Jerome” in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni) who when he took him out to the Lido for a “little sea bath” charged straight into the waves and was lost for three days. At last “he took the deep water in broad daylight, and swam straight for Venice. A fisherman saw him from a distance, rowed after him, took him, tired among the weeds, and brought him to me…I was then living on the north side of St. Mark’s Place, and he used to sit outside the window on the ledge at the base of its pillars greater part of the day, observant of the manners and customs of Venice.” Ruskin then took him home with him across the Alps (which, to Ruskin’s chagrin, made no impression on the dog) and when they stopped in Paris Wisie was equally unimpressed—but hearing a bark in the street which sounded Venetian jumped out of the window and fell over thirteen feet to the pavement below where he immediately picked himself up and trotted back up the hotel stairs and eventually returned to England where he lived for many happy years.

As Kenneth Clarke wrote in an introduction to Praeterita in 1948, Ruskin’s “chief merit was his power of analysis—the power of scrutinishing an object so patiently and so perceptively that he could reveal something of its true character”. The traveller today has much to learn from such an approach—often all too intent on hurrying on to visit the next place and rarely content with halting for long enough to fix his attention before a building or a painting or sculpture to take in its instrinsic value and try to understand how it was constructed and where its beauty lies.

Sicily’s emblem: the Trinacria

The three-legged trinacria is an ancient symbol. Researches trace its origins to the Phoenician sun-god Baal, and also to the Greek Apollo: the legs signify the sun’s course through the skies and the three main seasons of the year. They are also taken to represent the triangular shape of Sicily, with its three main headlands. After their successful colonisation of the 8th century BC, the Greeks dedicated the island to Apollo, placing the god’s head in the centre of the symbol, with his totem snakes (he gave two entwined on a stick to his son Asclepius). An alternative interpretation contends that the head represents the Gorgon Medusa. The device was revived in modern times when Frederick II of Aragon had himself crowned “King of Trinacria”, adopting the ancient Greek name for the island. The emblem is famously also used by the Isle of Man (but without the head, and with armour-clad legs). It was perhaps chosen by Alexander III of Scotland and Man in 1266, when he married a Sicilian princess and all things Sicilian were considered worthy of emulation. The emblem set on a red and yellow shield, with three ears of wheat emerging from the winged head, is now the logo of the Regione Siciliana.

The Venice equivalent of the anonymous Tweet?

Anonymous tweets: essential for protest against oppressive regimes or the safe refuge of trolls and people who make trouble for fun? The Republic of Venice confronted this problem too, and they came up with the Bocca di Leone, or ‘lion’s mouth’, a hole-in-the-wall box where citizens could post denunciations of their foes and neighbours. The illustration at the top on the left shows the Bocca di Leone on the Zattere, placed there for ‘denunciations against public health abuses in the sestiere of Dorsoduro’. There are few surviving bocche in Venice today. The most famous is in the Doge’s Palace. Most of them were destroyed by Napoleon, in his mania for altering the world order, to underline the fact that Venice’s autonomy was no more and that she was subject to the laws of Napoleonic France.

Commentators have often used the Bocca di Leone as an illustrator of how sinister the workings of Venetian justice and government were. But in fact the inquisitors of the republic were circumspect in their treatment of anonymous defamations. A good blog about this can be found at bit.ly/Mw0E48.

The other two illustrations show a surviving bocca in Verona, which elected to join the Venetian republic in 1405. It invites ‘secret denunciations against usurers and usurious contracts of any sort’. It is placed beside the door of the old Palazzo della Ragione. Above it once proudly stood the Venetian lion—until Napoleon’s men hacked it to death.