Philippe de Montebello in conversation with Martin Gayford, Rendez-vous with Art, Thames and Hudson, 2014.

Philippe de Montebello, French by birth but a New Yorker by upbringing, remains the longest serving director of the Metropolitan Museum, with 31 years to his credit when he retired in 2008. He is still very active and he arranged to meet with the English art critic Martin Gayford, where and when they could, to see and discuss some of the works that most fascinated them. This is the finely-illustrated record of their discussions.

I really enjoyed this book. Some of the works selected I knew; others I did not or had certainly never seen ‘in the flesh’. One of the very first, a sculpture that inspired Montebello when he first saw it aged 15, is the meditative face of Marchioness Uta from high up on the choir of Naumburg Cathedral. It is now, remarks de Montebello (with some regret that his secret love is out), posted everywhere on the internet, although it had passed me by and I was pleased to know of it. And then there is Donatello’s Mary Magdalene, the penitent’s nakedness covered in her flowing hair, that I have seen only once in Florence. The morning after the disastrous Florence flood of November 1966, de Montebello found himself alongside Harold Acton gazing at the mud-caked statue. Acton, having donned his hunting boots for the chauffeur-driven excursion down from I Tatti, was in tears.

De Montebello is unashamedly patrician. Visiting the magnificent Wallace collection in London he imagines himself at the opulent writing desk of 1770 created by Jean-Henri Riesener and ‘transported back into an era of unabashed luxury’. There is perhaps a tension here with Gayford, who notes that it is this ‘kind of dizzyingly luxurious living that helped to bring about the French Revolution’. It is doing no disservice to Gayford not to quote him here so often as de Montebello, as he plays his part well in drawing de Montebello out and then reflecting on what inspires this art historian in his choices: ‘a quality of silence and restraint, combined with compelling naturalism’ in one instance. Again, in the world of Art History where jargon and sociological theory so often threaten to come between the viewer and a painting, how refreshing it is to hear de Montebello comment on how ‘occasionally, it can be restful to contemplate comfortably, uncomplicatedly, something that makes you smile inwardly’.

For some readers, these leisurely strolls around galleries may all be too gentle and elitist. (‘A characteristic of great works of art is that they persistently catch our attention and beckon us’ catches the mood of time to spend.) And there is no more than the odd reference to anything modern. But once you have accepted this, you will find many good reflections, especially on the placing of art. What is the best context to show a painting and what is lost, for instance, by taking an altar from the church for which it was designed and placing it in a museum? How far does one’s appreciation of art depend on where a work is displayed in contrast to others around it? Is it possible ever to appreciate the Mona Lisa and other trophy works now that tourists hem them in, ticking them off their must-see (or must- photograph) lists? (Although I couldn’t help feeling that de Montebello would have been able to fix any secluded visit he wanted without difficulty!)

One of the most rewarding parts of the book describes how de Montebello came to purchase a superb Duccio Madonna and Child for the Met. Of course, it helps to have $45 million available for a single purchase, but the Louvre was after it as well. It is indeed a delightful work, a devotional image from the cusp of the transition from Byzantine to Renaissance and there is a wonderful tenderness in the way the Christ child reaches up to his mother’s cheek. De Montebello weighed it up, literally in his hands for an hour, as he worked through all the competing issues of quality, provenance and importance within the unfolding of new directions in western Art. Finally there is the ‘irrepressible need to win: to have won possession of the object of desire’ which brings everything to a climactic decision and the eventual purchase.

If I had to end my days in a large single room with 20 paintings by a single artist, I might well choose Chardin. De Montebello notes how a lovely example of Chardin’s work, La Tabagie of 1737 (‘about as satisfying and scrumptious a paint surface as exists’) in the Louvre, goes almost unvisited as it is on an upper floor away from the must-see superstars. By contrast, a visit to the Mauritshuis in The Hague is ruined for de Montebello by the massive posters of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring which put him off revisiting the original because they killed ‘the freshness of the experience, the element of surprise, of discovery…’.

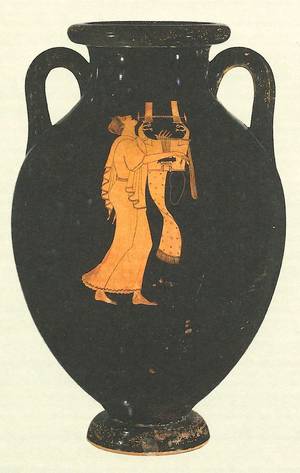

De Montebello is old-school in stressing the disciplined application required to appreciate art, and hence the need to avoid making museums places of transient entertainment. He notes how he had to be taken by his curator to view fragments of Greek vases to appreciate the quality of the painting, even more evident when seen on a complete vase. It was, in fact, one fragment of a single illustration, of a red-figure Greek vase from 490 BC, that beckoned to me. A scarf-like patterned fabric falls in a twist from a lyre… It drew me back more than once while I was absorbed in this civilized discourse on great art.

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, history consultant to the Blue Guides.

See this book on amazon.co.uk. See it on amazon.com.

Pedant’s corner: The Horses of St Mark’s are referred to in the book, as is usual, as being of bronze. In fact they are largely copper, a fiendishly difficult metal to cast. It has now been discovered that the gilding used to embellish them becomes blemished when applied to bronze but not to copper. Those 2nd-century ad craftsmen knew what they were up to. The horses are covered in detail in Blue Guide Venice. To make their acquaintance in greater detail still, see Charles Freeman’s The Horses of St Mark’s.