As bookshops continue to close down in cities across the world, the pleasure of browsing becomes ever more difficult to indulge. Shopping online is undeniably convenient, if you know precisely which title you want to buy. But how do you find out about those books you never knew you wanted? Thankfully in Budapest there are still plenty of places where you can give yourself over to the serendipity of the shelves. Here we list our favourites, not in preferential order, but adding them one at a time, as we revisit (and making sure always to leave with a purchase or—in the case of bookshops with cafés attached—to stop for a drink and snack).

1. MASSOLIT

Massolit is a very special place, an old-fashioned bookshop, enticingly and scruffily crammed floor to ceiling with titles on diverse subjects from Archaeology to Zoroastrianism, mainly (but not only) in English. It takes its name from the Soviet literary clique of Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita. A warren of interconnected rooms leads through to a garden courtyard at the back, where you can sit with your book and a drink. There is a bar in the main room where you place your orders (simple food is also available). Although right in the heart of Budapest’s ‘Party District’, well known for its rowdy ruin pubs, Massolit preserves an air of wonderfully nerdy calm, possibly because it serves no alcohol. A chalkboard notice kindly asks co-workers to remember to order something from time to time if they intend to spend all day there on their laptops.

Last visited: 28th May

Book: Selected Poems of Endre Ady

Drink: Cherry juice and soda.

Budapest VII. Nagy Diófa u. 30

Open until 7.30pm.

————————————————————————————————————-

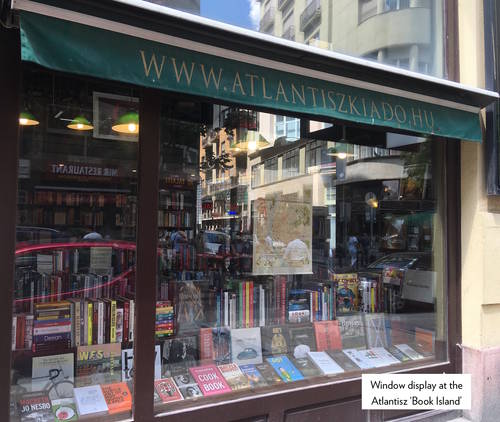

2. ATLANTISZ KÖNYVSZIGET

The Könyvsziget or ‘Book Island’ is a split-level bookstore belonging to the Atlantisz publishing house, whose list is strong on philosophy, history, art, classics and other Humanities subjects. Most of the ground floor is devoted to books in English and other languages. The location is extremely central, right behind Deák tér where three of the city’s four metro lines intersect and the terminus of the 100E airport buses. Visitors to Pest’s city centre and to the Jewish District will find this bookshop very handily placed. Service is friendly and there are one or two chairs for you sit down while you browse.

Last visited: 29th May

Book: Promote, Tolerate, Ban: Art and Culture in Cold War Hungary

(For a review of the recent exhibition at the Hungarian National Gallery dealing with Communist-era art censorship, see here.)

Atlantisz Könyvsziget

Budapest VI. Anker köz 1–3

Closed Sat from 2pm and all day Sun.

————————————————————————————————————-

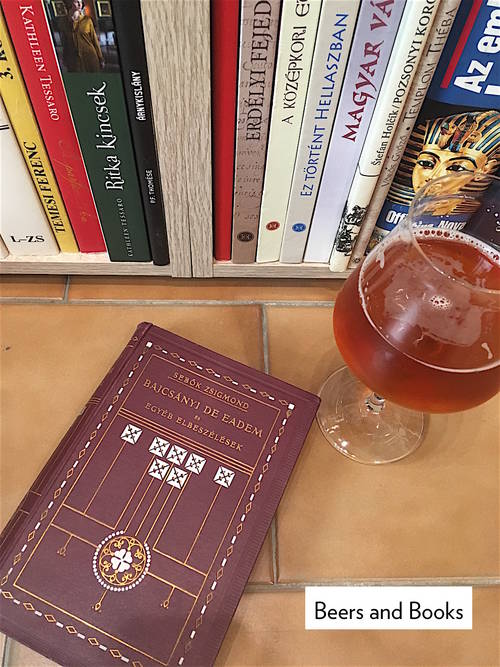

3. BEERS AND BOOKS

This is an eccentric and deeply delightful second-hand bookshop in Ujlipótváros, Budapest’s 13th District. You go down a few steps into a cool space lined on two sides with bookshelves, and on a third with an array of beers. You can buy either beer, or books, or both. It is also possible to drink a beer while you browse. I chose a bottle from the cool cabinet and it was poured out for me by the taciturnly friendly proprietor and served in a handsome long-stemmed glass. Beer in hand, you can pull up the high-backed faux-leather chair to a shelf of your choice and begin browsing. The offering is mainly in Hungarian but there is a small section of books in English as well. Not a chain, not a franchise, not an imitation of anyone else’s commercial prototype; this is a true Budapest original. The left-field choice of background music adds to the charm: on a scorching hot day in late May we were regaled with ‘Santa Claus is coming to Town’.

Last visited: 30th May

Book: Lajos Hatvany: Urak és emberek. A novel trilogy on the history of Budapest Jewry, from their arrival, through assimilation to persecution (for more on Lajos Hatvany, his family story and his brother’s celebrated art collection, see Blue Guide Budapest)

Drink: Monyó Flying Rabbit craft beer (for more on the Monyó brewery see Blue Guide Budapest)

Budapest XIII. Pannónia u. 46/b

Open until 9pm.

————————————————————————————————————-

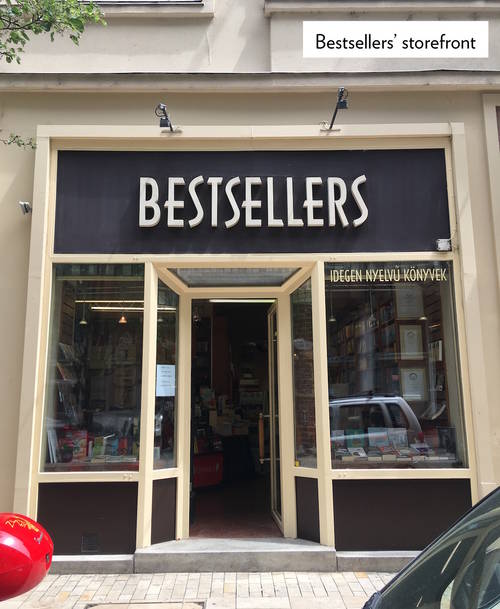

4. BESTSELLERS

Opened in 1992 by accomplished bookseller Tony Láng and still going from strength to strength after over a quarter of a century. Bestsellers has firmly established itself as the go-to destination for people looking for English-language books in Budapest. They have an excellent range of stock over many genres, including children’s books, newpapers and magazines. The section on Hungary and its history is particularly strong. Staff are well-informed and helpful. Browsing here is a delight. The location, slap bang in the heart of downtown Pest, could not be bettered.

Last visited: 31st May

Book: District VIII by Adam LeBor.

Budapest V. Október 6. u. 11

————————————————————————————————————-

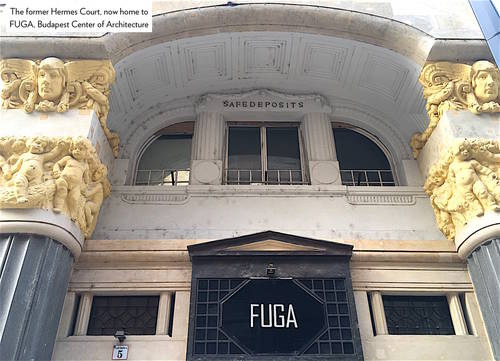

5. FUGA

The Hermes Udvar or Hermes Court, was built in 1905 for a company specialising in safe deposits. Operated as such until the First World War, after which the building was converted into flats. The architects, Géza Kármán and Gyula Ullmann, are known for a number of early 20th-century buildings in Pest, in a recognisably thickset, Seccessionist style. Today the Hermes Court is home to FUGA, the Budapest Center of Architecture, with a bookshop, café and exhibition spaces. The bookshop is excellently stocked, with a huge array of titles on fine art, applied art, architecture, urban planning etc in Hungarian and English, all enticingly spread out on the enormous central table. There are cosy nooks to sit and have a drink and at the back and upstairs there are exhibition rooms. The shows here are usually free and—naturally enough—take architecture as their subject matter.

Last Visited: 1st June

Book: Budapest Atlantisza by Emőke Tomsics, a study of the development of inner Pest in the late 19th century

Drink: Tomato juice

Budapest V. Petőfi Sándor u. 5

Closed Tues.

————————————————————————————————————-

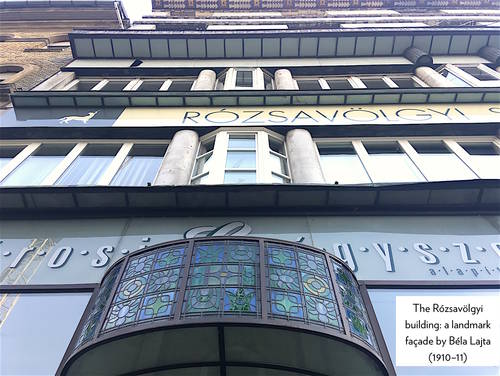

6. RÓZSAVÖLGYI

The Rózsavölgyi building is landmark example of Hungarian Modernism, built in 1910–11 by Béla Lajta. Part of the building is occupied by a chemist’s, the other by a bookshop. Historically Rózsavölgyi began life as a music publisher and shop, run by the son of a popular composer, and there is still a wide range of instruments, scores, sheet music and CDs on sale on the ground floor. At the front is a section of souvenir books and guides. Upstairs there are books on art and architecture, and further up still, the Rózsavölgyi Salon, which hosts muisc and theatre events and has a café (opens an hour and a half before performances).

Last Visited: 4th June

Book: Schirmer Performance Editions, The Classical Era (piano music)

Budapest V. Szervita tér 5.

————————————————————————————————————-

7. LÍRA

As the name, ‘Lyre’, suggests, this chain of bookstores specialises in music as well as in the printed word. They have shops well distributed across Budapest, in busy downtown areas of Pest as well as in residential districts of Buda (typically in shopping centres). The offering is wide, with a selection covering fiction and non-fiction, arts and sciences, adults and children and usually with a good range of titles in English and other languages. A link to the list of stores is given below. The illustration above was taken in the Múzeum körút bookshop opposite the Hungarian National Museum.

Last visited: 5th June

Book: Ignác Romsics: A Short History of Hungary

Líra (at many addresses across town; for a list, see here).

————————————————————————————————————-

8. HUNGARIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM

The bookshop of the Hungarian National Museum is in the building’s lofty Neoclassical lobby, to the left of the ticket desk. You can visit the shop without entering the museum. Its stock ranges from books to souvenir replicas, maps, posters and postcards. The books are often a motley bunch and it is always worth popping in to browse and to see what new titles have cropped up. There is always a selection in English and other languages. Titles held here are on history, art history and the museum collections themselves.

Last visited: 6th June

Book: The Dowry of Beatrice. Exhibition catalogue on Italian majolica and the court of King Matthias Corvinus

Drink: Sparkling mineral water. The museum has a café in the basement which you can only visit with a ticket. When the weather is fine, you can sit outside in the courtyard.

Budapest VIII. Múzeum krt. 14–16

Closed Mon.

————————————————————————————————————-

9. ÍRÓK BOLTJA

The ‘Writers’ Bookshop’ is not only famous for inhabiting the premises of the celebrated Japán Coffeehouse, haunt of artists and poets at the turn of the 20th century. It is also well known as the finest highbrow bookshop in the city. The shelves reach floor to ceiling (the topmost volumes are accessed by ladder) and the titles in stock cover poetry, fiction, philosophy, architecture, history, economics, law, sociology, theatre, gastronomy, design (and more). Books in English and other languages are on the upper gallery. The offering includes books on Budapest and a good choice of Hungarian literature in translation. There are also tables where you can sit and browse. Írók boltja often holds afternoon readings, discussions and other presentations: it is at the centre of a lively literary scene.

Last visited: 7th June

Book: Budapest Írókönyv (Liber ad scribendum). A beautifully presented anthology of archive photographs and extracts from prose and poetry thickly interspersed with blank pages, so you can write your travel journal. (The trouble is, the book is too beautiful to write in.)

Budapest VI. Andrássy út 45

Open until 7pm, daily except Sun.

————————————————————————————————————-

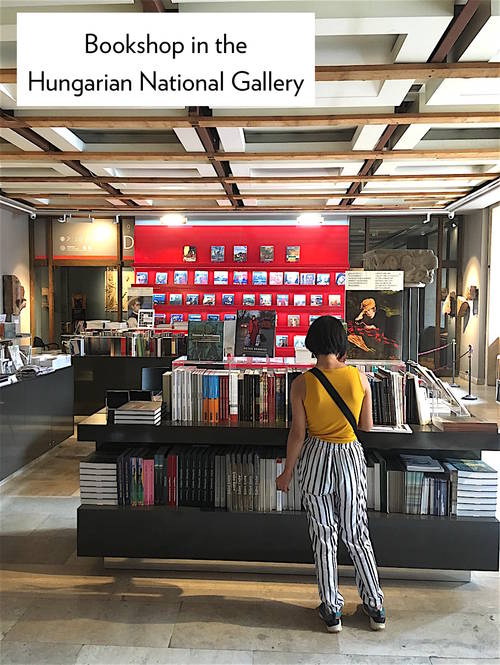

10. HUNGARIAN NATIONAL GALLERY

The bookshop attached to the Hungarian National Gallery, in the Danube-facing wing of the former royal palace on Buda’s Castle Hill, has an excellent selection of books and souvenirs. The books on offer include publications on Budapest and Hungary, exhibition catalogues, artist monographs and numerous works on art history, including a wide choice of titles in English. The shop is separated from the museum: you can visit the shop without an entrance ticket. The same is true of the café, which is in the opposite wing of the same building.

Last visited: 8th June

Book: Painting the Town Red by Bob Dent

Drink: Iced coffee

Budapest I. Castle Hill

Closed Mon.