Readers of these blogposts might have noticed our interest in the Seuso Treasure. We freely admit it. After all, these fourteen pieces make up what is arguably the finest trove of late imperial Roman silver in existence. And now, in a keenly-awaited move, it has become one of the permanent galleries at the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest with an impressive and spacious new display.

Since 2014, when the first seven pieces of the hoard were repatriated by the Hungarian government, we have written plenty about the silver and its convoluted history. To read about that, see here (also linked at the bottom of this article). This post will talk exclusively about the new display, which opened last week.

What is immediately striking is the solemnity. The visit begins in a long corridor, flanked by artefacts and information panels that give context and set the scene. The experience is a little like entering a processional dromos or sacred way, leading to an ancient temple or tholos tomb. At the end of the corridor is the inner sanctum, where the silver itself is displayed in a space made mysterious by plangent music. The air is thick with the silence. Custodians are keen to remind visitors not to take photographs. It is almost as if we were being inducted into an Eleusinian mystery, with the injunction never to divulge what we saw and heard when we return to the less rarefied atmosphere of our ordinary lives. Certainly not share it on Instagram!

Whereas the previous display of the silver was cramped, with the pieces crowded together, almost as if mimicking the tight packing in the copper cauldron in which they were found, the new exhibition arranges the items far apart. Those which clearly belong together (the Hippolytus situlae, for example) are displayed side by side. The others are their own islands.

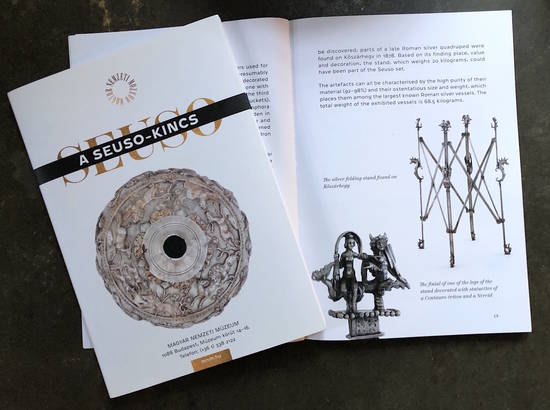

And now they are joined by the famous Kőszárhegy Stand (illustrated below), an adjustable four-legged contraption, a sort of luxury camping table, made of silver of the most extreme purity, purer than sterling. It was discovered near the village of Kőszárhegy, close to the putative find-spot of the Seuso Treasure itself, in 1878, during the chopping down and digging out of a plum tree. It was in a fragmentary state: two legs were unearthed together with most of two of the crosspieces. Restorers originally assumed that it had been a tripod, and integrated it accordingly. It was only when it proved impossible to prevent persistent cracking that the Museum team realised that it needed a fourth leg to make it stable and correct the tension. Two of the legs and X-shaped crossbars that you see today are original. The other two are restorations. The challenge is to detect which are which.The Kőszárhegy Silver Stand, in the Hungarian National Museum’s booklet on the Treasure.

The stand is an extraordinary piece, well over a metre high and capable of being adjusted to hold the largest of the Seuso platters. It is thought that it could have been pressed into service in a number of ways: to hold plates laden with good things at an outdoor feast, for example; or as a washstand bearing a silver basin and water pitchers. Its marine-themed iconography would support this view. Each leg terminates in a cupid figure riding a dolphin. Halfway up each leg is a sharp-beaked aquatic gryphon. The finials are decorated with silver tritons, clutching conch shells in huge-fingered hands, with water nymphs seated on their backs, naked but for a chain around their necks and a billowing veil above their heads. One of them holds an apple, the attribute of Aphrodite. As the information panel tells us, the Roman or Romanised Celtic domina who washed her face at this stand would have been flatteringly reminded as she did so of her own uncanny resemblance to Paris’s chosen goddess.

But the wealthy elite of Roman Pannonia were not goddesses or gods. As the central scene on the famous Pelso plate shows, they were a fun-loving bunch of mortals. They enjoyed picnicking in the open air beside Lake Balaton, scoffing freshly-caught fish and washing it down with beakers of wine. They loved their dogs and gave humorous nicknames to their horses. They threw banquets to show off their silver to each other, and display their erudition when it came to Graeco-Roman mythology. The characters that Seuso—whoever he may have been—chose to depict on his tableware, as reflections of his own attributes, were the great warrior Achilles, the great huntsman Meleager and the great reveller Dionysus. The women of his household are associated with Aphrodite, the Three Graces and Phaedra the temptress. These were people in love with life and merrymaking. So why the solemn atmosphere and the doleful music? Where are the dancing girls and the Apician stuffed dormice? The title of this display is “The Splendour of Roman Pannonia”: a good one; Seuso could certainly do bling. What he and his family left behind is ineffably precious. As well as revere it, we should also enjoy it, throw ourselves a little into the mood of carefree frivolity that these gorgeous pieces evoke.

The story of the Treasure on blueguides.com

Website of the Hungarian National Museum