Virtual museum tours: some of the best

For professional guides in Italy this is, of course, a period in which they suddenly find themselves without work. However many museums, while closed to the public, have made it possible not only to consult their catalogues or browse the collections online but have also opened virtual exhibitions. The Uffizi in Florence is one such example.

Easter is usually the busiest time of year in Florence, with hundreds of thousands of visitors. The traditional Scoppio del Carro is held in Piazza del Duomo on Easter morning. This year, however, there will be no visitors and no events—even church services must be attended remotely. Spring is definitely on the way, however, and the plants and birds at least are enjoying the sun and clean air as never before. The Uffizi’s ‘The Easter Story’, an exhibition on the theme of the Resurrection, will help us to look forward to better times ahead.

And the Uffizi is not alone in its response. Lisa Corsi, a professional guide who lives in Florence, has investigated some of the most interesting websites available in English at this period of universal lockdown and shared her findings with Blue Guides.

Italy

1. The Uffizi Gallery in Florence offers various online exhibits at this link: www.uffizi.it/en/online-exhibitions Here is a list of the current online exhibits, all with high-definition pictures of Uffizi works of art.

– “Non per foco ma per divin’arte. Dantean echoes from the Uffizi Galleries”. An excursus on the figure of Dante and on his legacy in the works and in the minds of the artists.

– “On being present; recovering blackness at the Uffizi Gallery”. The idea is to understand and resignificate with a historic approach, the presence of black people in the Uffizi paintings.

– “In the light of the Angels; a journey through 12 masterpieces of the Uffizi Galleries, between human and divine”. This exhibit is all about Angels; from Giotto to Giovanni da San Giovanni, with very good pictures.

– “Today a Saviour has been born to you: the Uffizi Galleries’ paintings on the Nativity and Epiphany”. A thematic exhibition.

– “Following in Trajan’s Footsteps; a virtual exhibition on items from the reign of Trajan present in the Uffizi collections”.

– “The Room of Saturn in the Pitti Palace; a history of the arrangements in the Room of Saturn, from the 16th century to the present day”. I found this interesting, and it also includes the latest changes from 2018 in the room that features the largest group of paintings by Raphael.

– “#BotticelliSpringMarathon A virtual exhibition on the construction of the contemporary Botticelli myth through social media”. An excursus on the fame and fortune of Botticelli from the 19th century to social media.

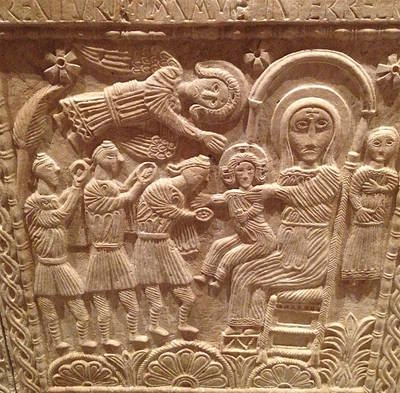

– “The Easter Story: Passion, death and Resurrection of Christ among the artworks of the Uffizi Galleries”.

– “Views from around the World; an ‘intercultural vision’ of some masterpieces of the Uffizi Galleries”.

– “The Scenic Virtuality of a Painting: “Perseus Freeing Andromeda” by Piero di Cosimo. A masterpiece of the Florentine Renaissance depicting the myth recounted by Ovid in Book IV of the Metamorphoses”. An in-depth approach to one of the Uffizi’s most unusual paintings.

– “Between Human and Divine: Cimabue and the Santa Trinita Maestà”. Observing the details of one of the most important medieval paintings in the Uffizi collection.

– “New languages to communicate tradition: Vanished Florence. Images of the city in the 18th and 19th centuries, before it became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy” This is fun, though mostly aimed at people who know Florence quite well.

– “Painting and Drawing ‘like a Great Master’: the talent of Elisabetta Sirani (Bologna, 1638–55)”. An exhibit on one of the rare women painters of the past.

– “Federico Barocci, master draughtsman. The creation of images; extraordinary examples from the rich collection of the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Uffizi”.

– “Amico revisited. Drawings by Amico Aspertini and other Bolognese artists; discovering marvels from the collection of prints and drawings of the Uffizi”.

– “Traces 2018. Letting fashion drive you in the Museum of Costume and Fashion”.

– “Traces. Dialoguing with art in the Museum of Costume and Fashion”.

– “The World of Yesterday: rare book collection of the Library on view”. These 39 books tell us the fascinating story of Pasquale Nerino Ferri (1851–1917), the first director of the Uffizi’s Prints and Drawings Department, through analysis of his handwritten notes and the dates and dedications written by his correspondents from all over Europe.

2. The Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan has a good site. The online collection features 669 records, all with high-resolution images and information on the various works. At this link pinacotecabrera.org/en/collezioni/the-collection-online you can browse the collection searching by author, material, date, etc. There is also a section dedicated to the masterpieces which features (with great pictures) the 11 most famous paintings in the collection (by Raphael, Piero della Francesca, Caravaggio, Mantegna, Gentile and Giovanni Bellini, Hayez, Boccioni, Pellizza da Volpedo and Modigliani).

3. Also in Milan, the Museo Poldi Pezzoli offers an online catalogue of many of its artworks. It is very well done. The museum was once the house of the art lover and collector Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli (1822–79). Here’s the link to its site: museopoldipezzoli.it/en/artworks.

4. Virtually visit the Palazzo del Quirinale in Rome and its grounds. It is the residence of the Italian head of state, the President of the Italian Republic, currently Sergio Mattarella: palazzo.quirinale.it/visitevirtuali/visitevirtuali_en.html.

5. Also in Rome the Galleria Borghese offers good pictures and a little explanation of some of its artworks: galleriaborghese.beniculturali.it/en/il-museo/autori-e-opere.

Rest of the world

6. The Archeological Museum in Athens has a good site, very easy to navigate. Here’s the link: www.namuseum.gr/en/collections.

7. The Prado Museum in Madrid has a great site with lots of artworks featured by artist, by century, by theme. Here’s the link: www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-works. And here are the Prado masterpieces: museodelprado.es/en/the-collection.

8. The British Museum in London has a very good site that allows you to browse the collections and also to virtually visit its rooms. Very well done. Here’s the link: britishmuseum.org/collection.

9. The Metropolitan Museum in New York (metmuseum.org) has an online collection: metmuseum.org/toah/works.

It also offers an interesting “Timeline of Art History”: metmuseum.org/toah/chronology/#!?time=all&geo=all. There are also many essays that can be read online at its link: metmuseum.org/toah/essays

And some videos: metmuseum.org/art/online-features/met-360-project.

10. The site of the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg is very impressive and offers different possibilities, including a virtual tour of the rooms.

There is also the “Explore the Hermitage” section, where you can choose to learn more on a single work of art, or learn more on the buildings, visit the online collection and more. Here’s the link.

The only downside is that this is a very “heavy” site to navigate and it requires a fast internet connection and a good computer.

* * * * *

Dante Day

Italy is still in the front line of the battle against Coronavirus, with more deaths in a day (475 on 18th March) than in any other country including China. The population is taking lockdown seriously and inevitably the use of the web from home-users has increased enormously. I was interested to see reports in the newspapers of the forthcoming ‘Dantedì’, instituted by the Minister of Cultural Affairs. The idea is to make 25th March into an annual celebration in honour of Italy’s greatest poet, Dante Alighieri. The date has been chosen as it was on that day in 1300, under a full moon, that Dante and Virgil begin their week-long journey from Hell through Purgatory into Paradise in The Divine Comedy. March 25th is also the feast-day of the Annunciation, which began the new year in the Florentine calendar up until the 18th century.

The day is intended to celebrate Dante and the Italian language. This year’s celebration was planned as an ‘antipasto’ to the great events scheduled for next year, 2021 which marks the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death. With the country in lockdown, no public events can be held in the piazze this year, but there will be numerous events online and on television.

Dante (1265-1321) was born in Florence and the city later provided the great human melting-pot from which the poet took inspiration for some of the most memorable characters of the Divina Commedia. Dante also served a two-month term as one of the six priors in the Florentine government in 1300. During his absence in Rome, as part of an official delegation to Pope Boniface VIII, he was accused of fraud and corruption by a faction of the Guelf party and when he failed to return in 1302 to defend himself he was sentenced to death. He chose to go into exile and was never to return to his beloved city.

The Divina Commedia was written during his exile and in it he re-elaborated, with amazing imagination and poetic skill, the classical myth of the descent into Hades. It provides an astonishing ‘summa’ of medieval culture, but this epic poem is also written in a language (partly created by the poet himself) which is as close to modern Italian as Shakespeare’s language is to English today. What perhaps impresses us most in the poem is that Dante, while providing a vibrant fresco of the political and religious controversies of his time, is also able to tell us about himself, about his friends and enemies, about his teachers, his passions and his religious belief. The Commedia is about a man called Dante Alighieri, who finds salvation thanks to the love of the angelic Beatrice. But author and ‘hero’ are one and the same: Dante’s fede (faith), which he defines as ‘the substance of our hopes’, permits him to assert that the story that he tells actually took place. And when we read the Commedia, it is very difficult not to believe him.

The poet died (and was buried) in Ravenna. Naturally he features in our description of that city in Blue Guide Emilia Romagna, but he is also frequently recorded in other Blue Guides, because so many buildings and monuments in Italy are mentioned in his poem. But it is in Florence where his presence is felt most: in the medieval area where he lived, in the places he describes (now marked by marble plaques), in the monuments inside and outside Santa Croce, and in the frescoed portraits of him which still survive in the city.

Florence was also the birthplace of Boccaccio (1313–75), a great admirer of Dante. He experienced the great plague of 1348, which in his Decameron becomes an allegory for the moral decay of his time. It is for this reason that Boccaccio’s stories, written in beautiful and articulate prose, should not be regarded simply as examples of literary originality and of a Renaissance sense of humour. The tales recounted in the Decameron are told by three young men and seven young women who, in order to escape a city devastated by plague (and also by greed and avarice) find refuge in a villa near Fiesole, where they create a world in which the mercantile mentality is refined through a rediscovery of the values of classical humanitas and courtesy. With a lightness of touch and true wit, Boccaccio reminds us that the first step towards creating a more humane society is to recover the precious art of story-telling.

In these dire times we have much to learn from these two great medieval literary figures.

Alta Macadam. Florence, 22nd March 2020

I gratefully acknowledge the help of my son Giovanni Ivison Colacicchi in interpreting the poetic significance of both Dante and Boccaccio. Giovanni and his companion Elisa are at present in lockdown in Ferrara in Emilia-Romagna, one of the regions of Italy worst hit by Coronavirus, but they are lucky enough to be able to carry on their teaching activity from home, and their 3-year-old son Francesco is greatly enjoying their presence, 24 hours a day.

* * * * *

Pope Francis takes a walk

With Italy in lockdown because of Coronavirus, we were treated to the extraordinary sight of Pope Francis walking along the deserted Corso in Rome from Piazza Venezia to the church of San Marcello. He decided to make this gesture of solidarity and hope to the faithful since the church contains a Crucifix said to be miraculous. He went in and knelt before it, a lone figure, to pray for the end of this current ‘plague’. On the same day he also went to the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore to offer up a prayer before the greatly venerated image of the Madonna which for centuries has been known as the ‘Salus Populi’ or ‘Saviour of the People’. These simple gestures, typical of the present Pope and made totally regardless of security, were seen by many Italians as an encouragement to all at a time when, for the first time in history, churches all over the country are forbidden to hold services.

We have just brought out the 12th edition of Blue Guide Rome and in fact had expanded our text on the San Marcello Crucifix, which now reads as follows: “Today the church has become a site of modern pilgrimage, with a banner on the façade proudly advertising its ‘Crocifisso Miracoloso’ or wonder-working Crucifix […] a 14 th -century Cross which was greatly revered by Pope John Paul II, who in the year 2000 had it moved to St Peter’s during Lent”. For the future 13th edition will remember to note this historic visit by Papa Francesco.

Many will be sceptical about the miraculous element in this story but no one can deny that it was a spontaneous act of faith and encouragement from a pope greatly admired for his closeness to the people. The fact that he left the Vatican to pray before this precious ancient work has encouraged a feeling of involvement in a country and a city where a great many devout Catholics are now isolated one from the other. We are told that the Pope is now in confinement at Santa Marta, just as we are in confinement in our own homes.

Alta Macadam, 15th March 2020

* * * * *

Letter from Italy

With the closure today of the museums and monuments in all of Italy, those of us who visit them also for work are left wondering how such a thing could have happened in our lifetime. We suddenly find ourselves facing a drastic shortage of culture: no libraries, no theatre, no cinema. However, the very direct explanation by Prime Minister Conte late last night made it all too clear how necessary such measures have become in a country where the dreaded Coronavirus is suddenly holding us all hostage. There is no doubt that Italy has trusted leaders in Conte and President Mattarella, and the country’s medical profession are displaying all their dedication and efficiency. There is an evident preparedness in those in places of responsibility and a feeling of teamwork and pulling together in times of emergency. Millions of other Italians have merely been asked to stay at home for the time being. A measure which seems eminently sensible and which should not be a great sacrifice. Who knows how this forced restriction might even foster closer family relationships and make the homes themselves more comfortable. My garden will certainly enjoy greater attention. And with all the benefits of the internet, no one need feel cut off. There is even hope that the closure of museums and monuments will give those great institutions a chance for practicalities impossible when they are open all the time—even if only some radical cleaning, but also perhaps some reorganisation—an almost welcome pause to ‘stand back’ and contemplate themselves and their ‘mission’. I look of course on the rosy side of things, the side for those fortunate enough to have families and homes, but there is a very ugly side of this ‘shut down’, such as the situation in the overcrowded prisons, or that of people cut off from their families who are in hospitals or nursing homes, and the extremely dire economic consequences. This situation is making us all wonder about how we should live our lives in the future, about how long we can expect to enjoy ‘normal’ life in our global world.

For my involvement in the Blue Guides to Italy (Blue Guide Rome has just been published) it means I cannot set off for Venice and the Veneto for work on a volume coming up for revision: a restriction which has been imposed on me for the very first time by circumstances beyond my control (the only other time this happened to me was when I had to cut short a trip for Blue Guide Northern Italy when I was staying in Trieste the day of the terrible earthquake which hit the Friuli in 1976).

We can but hope the virus will soon be dominated with the help of everyone round the world and that we will soon return to a life as we know it, if greatly sobered by what has happened to us all.

Alta Macadam. Florence, 10th March 2020