Christianity did not conquer the Roman Empire with the sword—and yet it was with the sword that the groundwork was laid, at the Milvian Bridge. Today the place is peaceful: but this not particularly impressive-seeming footbridge over the Tiber was the scene, in late October of the year AD 312, of one of the pivotal battles of Western history, where the forces of Constantine vanquished those of his rival emperor Maxentius.

The bridge today is not very much frequented, except by lovers, who used to come here to clip a padlock to one of the bars placed at intervals along it as a symbol of everlasting attachment. The clotted love tokens have now been removed and unimpeded you can peer over the parapet and look down on the Tiber below, watch it burbling swiftly over a shallow cataract, and imagine the clash and clamour of horses and men.Frieze from the Arch of Constantine showing Maxentius’ horses and men floundering in the water of the Tiber.

Maxentius championed Rome. He made it his capital—he was the first emperor for a hundred years to do so—and set in motion a train of great building projects aimed at restoring the city to its central position within the empire, not just symbolically but actually. He named his son Romulus and dedicated a temple in the Forum (either to his dead son or to the great eponymous founder of the city). His sister Fausta married his co-ruler, the man whom Shelley ostentatiously called the ‘Christian reptile’. Constantine was not so much reptilian as amphibious. He was born a pagan but emerged from the water as a Christian, and so died.

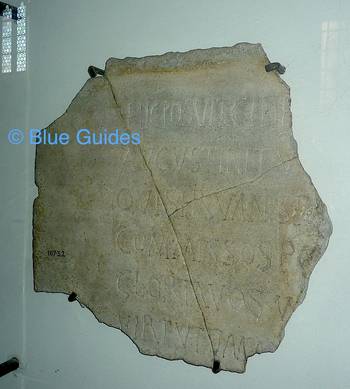

And he was unable to share a throne with Maxentius. The two soon came to blows, and battle lines were drawn at the Milvian Bridge across the Tiber. In order, as he hoped, to cut off his adversary’s retreat, Maxentius had destroyed the bridge before the battle commenced. It was an action that proved his undoing. With his horses and men he was forced back into the water and there drowned, yielding the day to his rival. Constantine built an arch to celebrate his victory. It is one of the most famous of Rome’s surviving ancient monuments, standing beside the Colosseum. On its short west face is the goddess Luna in her two-horse chariot. On the long south face is a scene of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. The short east face has a roundel of the sun god rising from the ocean and a depiction of Constantine’s adventus into Rome. On the north face we see Constantine in Rome distributing gifts. The inscription which appears on both the north and south faces (identical on each) contains a famously ambiguous religious reference to a ‘divinitas’, a divinity, in the singular. What or who was this god? It is an early and important witness of the slow change from the worship of many deities to the worship of a single, all-powerful one. The process by which this happened is fascinating and can be traced all over Rome in its art and architecture.

IMP·CAES·FL·CONSTANTINO MAXIMO

P·F·AVGVSTO S·P·Q·R

QVOD INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS MENTIS

MAGNITVDINE CVM EXERCITV SVO

TAM DE TYRANNO QVAM DE OMNI EIVS

FACTIONE VNO TEMPORE IVSTIS

REMPVBLICAM VLTVS EST ARMIS

ARCVM TRIVMPHIS INSIGNEM DICAVIT

“To the Imperial Caesar Flavius Constantine, the Great, Pius, Felix, Augustus: inspired by a divinity and in the greatness of his mind, with his army and by the just force of arms he delivered the state both from a tyrant and from all his faction; thus the Senate and the People of Rome have dedicated this arch in token of these triumphs.”