Rome has been in the Press quite a lot recently. News about the ban on snacking around ancient monuments in the city centre has spread like wildfire across the ether’s social media platforms. The despair of Vatican officials and their cluelessness about how to handle the Sistine Chapel’s five million yearly visitors has made headlines. Any suggestion that visitor numbers should be limited provokes cries of “Snobbery! Elitism!” Alternative suggestions that nothing can be done are clearly untenable, if we want Michelangelo’s masterpiece to survive. Personally I don’t care for Michelangelo’s masterpiece (though I do want it to survive). What I love are the earlier paintings around the walls, by Botticelli, Perugino et al, which one can never see or appreciate properly because the myriad heads of the teeming crowds get in the way. In many ways it isn’t so much the number of visitors that is the problem, but their voluminousness. There are so many organised groups, disgorged from coaches or from cruise ships. This is their chance to stretch their legs, though the itinerary isn’t precisely of their choosing and they move inefficiently, plodding along with audio packs slung round their necks and a loud lady with an umbrella marshalling them from the front. I know, I know, I’m an elitist and a snob…

But I am not going to discuss this any further here or attempt to offer a solution. Largely because there is no solution. Five years ago, Rome was not like this. The Forum was still free of charge and you could wander in at will at any time of day or night. There were no lines in front of St Peter’s snaking all around Bernini’s colonnade. St Peter’s Square wasn’t barricaded like a football stadium which dreaded a clash between particularly thuggish fans. But it is now. And you often have to wait for 20 or 30 minutes before you get to the front of the line. And the ticket staff at the Forum are rude. And the fake handbag vendors have arrived in force. The city has fallen victim to its own loveliness. And when visitors begin to find it unlovely—as they are starting to—they will go off and find another place to colonise, like aphids on the underside of a rosebud. And we can’t do anything to stop it because we’re all involved. Those who write guide books; those who sell aeroplane tickets; those who run restaurants; those who drive taxis; those who need money in the municipal coffers to mend the roads; those who want their archaeology projects funded. And those who want to travel to the place where Caesar fell.

Rome is not unique. There are places all over Europe which are no-go areas for the independent traveller. I visited St Paul’s in London two weeks ago and had an appalling experience. It cost me £15 and I was shooed out after having seen about a third of what I wanted to. It will be difficult to tempt me back. When in Venice, it wouldn’t cross my mind to try to see St Mark’s. In Paris, I avoid the Mona Lisa as if she were a leper. Rome, which was once my favourite city, is now going the same way. I used to love popping into St Peter’s or the Vatican Museums. But I’ve started to choose not to. Last time I was in St Peter’s, nerdily trying to decipher an inscription, a largish lady asked me to get out the way because I was spoiling her photograph. I obeyed and went off in search of the tomb of Pope Innocent XI. I asked a young guard, and he told me it was in the crypt. It isn’t. It’s in the north aisle. Then I tried to go to the Cappella del Sacramento to say a swift prayer. A different guard saw the Blue Guide in my hand and stopped me at the entrance, saying the chapel was not for tourists, only worshippers. “Can’t one be both?” I asked him. He thought not. I insisted, was admitted, and ended up not enjoying the experience because I felt a fraud. I didn’t only want to talk to God. I wanted to look at the tabernacle on the main altar, which is particularly fine.

I spend my life researching and writing guide books. And I know that it isn’t good enough to tell people what a horrible time they’ll have if they visit the Uffizi, the Eiffel Tower, Harry’s Bar, the Colosseum. I need to find things that they will enjoy. So here is my Rome alternative to St Peter’s: San Lorenzo fuori le Mura.

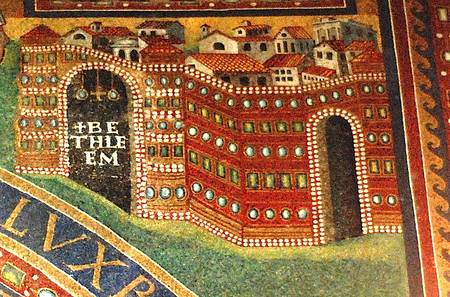

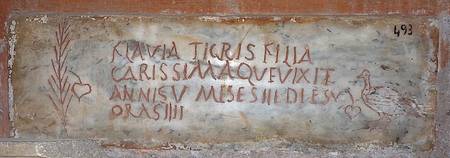

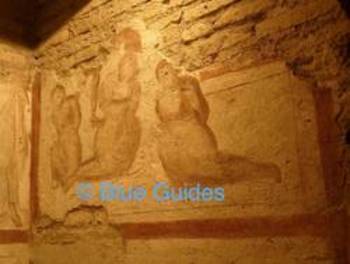

Like all the early Christian basilicas (including St Peter’s), it was built outside the city walls. It stands above the tomb of an important early martyr. Not one quite as illustrious as St Peter, but even so, Lawrence was a deacon of the early Church, martyred in Rome in 258 during the persecutions of the emperor Valerian. It is said that his body was roasted on a grid-iron. More than any of the major basilicas, it retains an aura of what these churches may once have been like. It retains its lean-to porch, supported on fluted columns. Its floor is beautiful porphyry and marble inlay. It has a venerable pulpit with Cosmatesque decoration. The mosaics of its triumphal arch are in the best tradition, a procession of saints between the holy cities of Bethlehem and Jerusalem. In the crypt you can see the slab whereon St Lawrence’s body reportedly lay after death. Here also is the mausoleum of the longest-reigning of all the popes, the controversial Pius IX, who lost Rome to the invading national army and was confined for the rest of his life to the tiny Vatican. He lies in state in brilliant scarlet, his face covered by a silver mask. The little cloister walls are covered with inscriptions from the early burial ground, and below it is a small catacomb, which can be visited with relative ease (ask the sacristan), unlike the catacomb under St Peter’s, which requires months of emails and faxes—and even then may result in nothing. San Lorenzo also stands in a part of town which is home to large numbers of Chinese and Bangladeshis. It is out of the mainstream. The first communities of Christians would have been in just such an area, far from the disapproval of patrician citizens. It is an evocative place and a very lovely one. And you will probably have it almost to yourself.