The celebrations to mark the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) have already begun, with the Uffizi’s exhibition of the Leicester Codex. Purchased in 1717 by Thomas Coke, Earl of Leicester, the Codex was preserved in the UK by the family until it was sold to Armand Hammer in 1980. In 1994 it was acquired by Bill Gates, who has lent it to Florence for this show (which runs until 20th Jan). The curator is Paolo Galluzzi, director of Florence’s Galileo Museum.

The Codex was compiled while Leonardo was living in Florence at Palazzo Martelli, and it concentrates on the theme of water. At the entrance, the visitor is invited to ‘walk across’ the waters of the Arno to see a reproduction of the famous Pianta della Catena, a bird’s eye view of Florence made at the end of the 15th century, which highlights the places frequented by Leonardo when he was at work on the Codex. Apart from working on the ill-fated fresco of the Battle of Anghiari (described in Blue Guide Florence), he also studied anatomy by dissecting corpses at Santa Maria Nuova (still functioning as a hospital today) and measured the Rubiconte bridge (now replaced by Ponte alle Grazie), observing the force of the Arno sweeping past its pylons in the river bed.

While writing the Codex, Leonardo also consulted the works of earlier natural scientists in the library of San Marco, seven volumes of which have been lent to the exhibition (their authors include Pliny the Elder, Ptolemy and Strabo). Two others of particular interest are a tract by John of Holywood (known in Florence as Giovanni Sacrobosco, lit. ‘holy wood’), born in Halifax, Yorkshire at the end of the 12th century, which was still a celebrated work in Leonardo’s time; and the treatise on architecture by Francesco di Giorgio, which has margin notes in Leonardo’s hand.

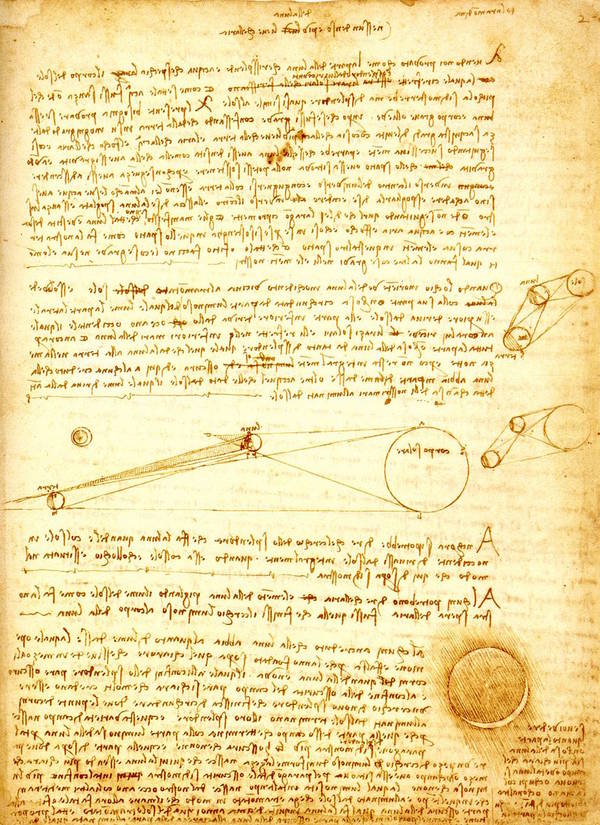

The Codex itself, with its closely filled pages (recto and verso), written from right to left and crowded with sketches, is displayed in 18 showcases. Leonardo’s famous ‘mirror writing’ is explained by the fact that he was left-handed, making it easier and faster for him to write like this. In the centre of the hall are some five touch screens where the Codex can be ‘read’ in its entirety (also in English), with aids to its understanding. These are installed low enough for children to use (but it would have been nice to have benches in front of them in order to sit down).

Animated diagrams and reconstructions show how closely Leonardo studied the structure of water, from a dew drop to ocean waves, from springs to the dynamics of water flow and the erosion of river banks, from moisture in the air to the steam created by heating water, from the prevention of floods to the invention of locks along canals. He even describes how the eye perceives sunlight reflected by water. He suggests that water can be harnessed for the good of man if it is coaxed (rather than coerced) into different directions, and his plans for the drainage of the Arno basin, and for a canal to link Florence to the sea, are illustrated. The words invented by him to describe water, in all its various aspects and infinite movements, are pointed out.

Parts of the Codex are also dedicated to the moon, which Leonardo recognised as having the same physical nature as the Earth. He describes the Earth as containing a ‘vegetative soul’ and suggests that the flesh, bones and blood of living creatures are related to the Earth’s soil, rocks and water. His geological studies led him to understand the origin of fossils found on high ground formerly covered by the sea.

Some other treatises, written by Leonardo at the same time as the Leicester Codex, have been lent to the exhibition: one on the flightpaths of birds and experiments in mechanical wings (lent by the Biblioteca Reale in Turin); two (smaller) double sheets from the Arundel Codex about the canalisation of the Arno (lent by the British Museum); and four sheets of the Codex Atlanticus (lent by the Ambrosiana in Milan).

This is an exhibition dense with information that attempts to explain Leonardo’s complicated mind and to compass his interests, which darted from one observation to another. It succeeds in producing a picture not only of his deep scientific knowledge but also of his humanity, so many centuries ahead of his time and based on precise observations of the world about him.

The excellent catalogue is available also in English and the exhibition has a website.

by Alta Macadam, author of Blue Guide Florence and co-author of the forthcoming Blue Guide Lombardy (details to follow shortly on this website).