“Those who Built Budapest” is the title of an absorbing one-room exhibition currently on show at the Budapest History Museum (in the ex-Royal Palace on Castle Hill) and prolonged until September. The title of the show deliberately doesn’t use the word “architect”. The lens through which the city is viewed is emphatically that of the masons, carpenters, joiners, metalworkers and other artisans who collaborated to create the extraordinary Historicist cityscape that came into being during Hungary’s golden age: between the Compromise with Austria in 1867 (the foundation of Austria-Hungary) and the outbreak of World War One.

The artisans were trained explicitly via the precepts of the past. This exhibition looks at the models they were exposed to, the way their aesthetic taste was formed, the frames of reference they were given and the precedents they were taught to follow, all under the auspices of the Metropolitan Industrial Drawing School, which grew out of the old Buda and Pest drawing schools (founded in 1778 and 1788 respectively). The methodology was explicitly imitative. Students were taught to create by being trained to make precise copies, in drawing and sculpture, of exemplars from antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

If anyone has stopped to wonder why late 19th-century Budapest architecture was almost exclusively “neo” (Neoclassical, neo-Romanesque, neo-Gothic etc), here is the answer. It was not until the turn of the 20th century that architects began to think outside these boxes and strive to create a new idiom, the Secession or Art Nouveau.

The material available to the students came in two main forms: pattern books, which were essentially albums of prints of historic examples; and plaster casts. The Drawing School had almost 2,000 of the latter, organised in different categories: elements from Classical Greece and Rome, for example; plant and animal designs; anatomical models. A few of them are on display here. There is a scale model of an ancient Greek theatre, casts of temple entablatures and an (exquisite) reproduction of one of the Corinthian capitals from the 4th-century BC Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens.

The material that illustrates this exhibition comes from the Schola Graphidis collection of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts-High School of Visual Arts. The pattern books on show contain prints of architectural ground plans and façades of the buildings of Rome; of decorative paintwork in France; of architectonic elements from Classical antiquity.

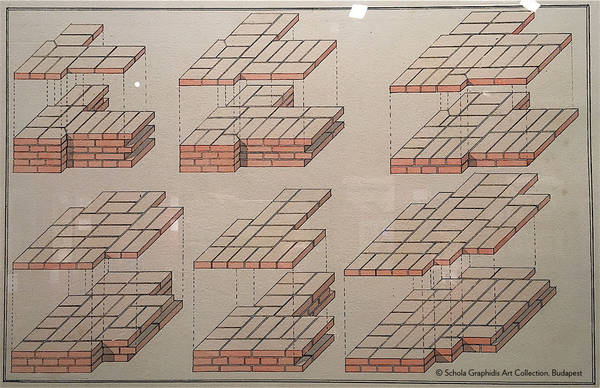

But the most fascinating exhibits in this show are the works of the students themselves, ranging in date from the 1860s to c. 1920. There is apprentice stonemason Ferenc Dobrovits’s 1884 study of a façade, for example (it could almost be by Bramante); apprentice joiner János Szuchy’s 1899 study of varieties of brick bond (lovelier in its way than Carl Andre’s celebrated and controversial Equivalent VIII!); Mihály Kiss’s delicate watercolour study of different types of arch (1910) and Gyula Csík’s dramatic pen-and-ink wash drawing of a Tuscan Doric column capital and base (1870s). These and many others are works of Ruskinian beauty.

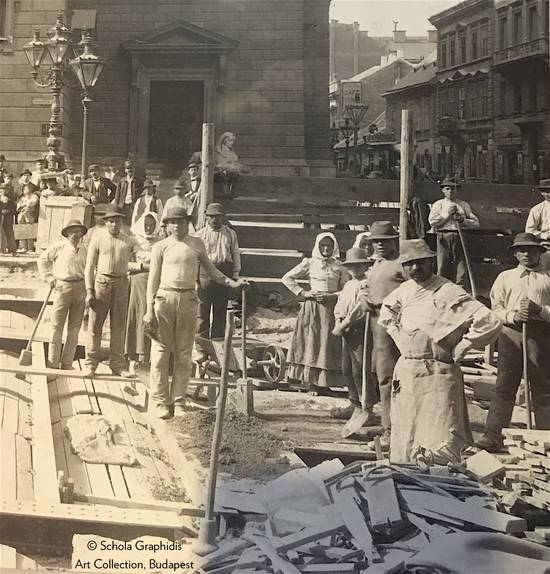

The show is rounded off by a short series of photographs by György Klösz documenting the construction of the cut-and-cover Millennium Underground in 1894–6, Budapest’s M1 metro line or Földalatti, which runs beneath Andrássy út to City Park and beyond. There is a shot taken outside the Opera House showing a cluster of construction workers, men, women and children, equipped with simple spades, not a hard hat or hi-viz jacket in sight. Also fascinating is the photograph of the underground station entrances on today’s Vörósmarty tér. They have disappeared now, but Klösz’s photo shows them standing like twin jewel caskets, purely Italian in spirit, reminiscent of Pietro Lombardo’s 15th-century church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli in Venice.

Lovers of Budapest belle-époque architecture should definitely see this show. After seeing it, it is impossible not to scrutinise every late 19th-century building in the city, looking for tangible application in bricks and mortar of all the artisans’ training. The rigour and discipline of that training was something quite extraordinary.