Elizabeth Bowen: A Time in Rome. Reviewed by Charles Freeman. Originally published by Longman (1960). Reissued by Vintage Books.

I wonder how much the novelist Elizabeth Bowen (1899–1973) is read now? Bowen was of Anglo-Irish stock, a fine but delicate writer acutely attuned to the cadences and concealments of an elitist society that had lost its purpose in an independent Ireland. She has been described as ‘haunted by loss’, her characters pulled back into a past that cannot return. Perhaps it is this for which she is still remembered, as much as for her evocation of the atmosphere of a place, notably the Irish country house, or London in the midst of war.

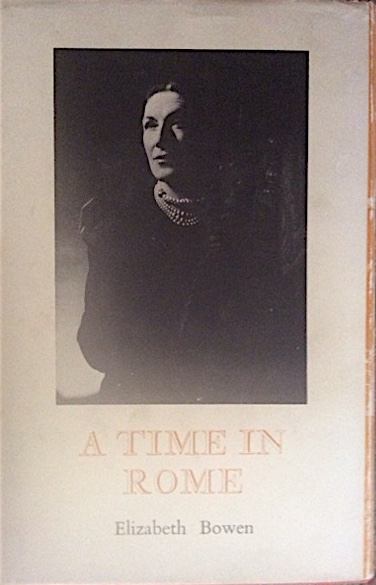

It was for this evocation of place that I was recommended her A Time In Rome, a memoir from when she spent some months in the city in the spring and summer of 1958. What I had not expected when I ordered a cheap second-hand copy on the internet was a first edition still in its original dustwrapper. It is a pleasure to own. The author, with her aristocratic nose, elegant coiffure and several strings of pearls, is shown on the back, a shadowy arch of Septimius Severus behind the title on the front.

This is not a coherent account. It is, as I was told to expect, an evocation by someone who had time on her hands, is interested enough in her surroundings and its history, but perhaps prone to be didactic, making sure that we know all the ancient roads leading from Rome, the names of the gates in the Aurelian wall, and what might or might not count as one of the Seven Hills. She is brisk about the inadequacies of the Forum: ‘This might be an abandoned building-site, or outgrown giant playroom littered with breakages.’ We are firmly told how to negotiate the ruins despite there not being an entry gate just where she would have liked to start. She is not drawn to Roman ruins.

Her wanderings go hand in hand with her battles with her piante, the only maps of Rome that she can find. They are large and brittle and need to be unfurled every time they are used; in the winds ‘the Pianta forever was rearing up to wrap itself blindingly round my face’. There was a struggle to unfold them on a café tables without staining them with coffee or butter and there had to be frequent new purchases after each one disintegrated along its folds.

Still, despite her frustrations, Bowen allows herself to absorb the city. She enjoys the less pretentious restaurants, watching the regulars treating them like home, marvelling at the pride of the waiters, even in trattorie that have nothing to be proud of. The secret of success is ‘a matter of freshness, resilience, tenderness, and in the case of pasta sufficient slipperiness without oiliness’. She revels in the revival of Renaissance Rome, especially the Via Giulia, ‘One rejoices in positive spaces, like giant ballrooms, connected by corridors of perspective. The longer the distances to look down, the greater the pleasure.’ Despite an air of Protestant hauteur about the extravagances and intolerances of the Catholic Church, the vistas created by Pope Sixtus V (r. 1585–90) are especially valued. The pope ‘brought Rome’s extravagant distances and bewildering contours into a discipline which is beautiful.’ She is sensitive to the burgeoning of Rome’s spring in the Borghese gardens and other less known gardens. ’I associate the Parco Savello [on the Aventine] with singing birds, the columnar lines of the slender trees, and reposefulness—here in so green a space, at so great a height, above Rome.’ The garden frescos from the Prima Porta villa of Livia, the wife of Augustus, delight her and it seems, from the way she admires Livia’s grace and courage, that she found a kindred spirit in the empress.

When asked by acquaintances why she is in Rome, Bowen cannot give an answer. Her husband had died in 1952 but it had never been a close marriage (apparently never consummated). Her lover, a Canadian diplomat, Charles Ritchie, had married during the affair, which lasted over 32 years, leaving a possible life with him unresolved. She was overwhelmed with debts on her beloved Irish home, Bowen’s Court, which she would eventually have to sell. Rome may have been an escape but there is nothing to shape her apparently solitary days or her narrative. Her wanderings seem serendipitous, ‘one or another desire or curiosity shaped my courses for runs of days’. She is reticent, prefers to learn from watching rather than engaging in conversation.

So this is the memoir. Yet many of her letters to Charles Ritchie survive and I found a quote from one of them that was written from Rome. ‘I am leading a very gay, amusing, glamorous, sumptuous life’, she writes. There is nothing of that in her memoir and so a mystery hangs over this book. It is not one of the great evocations of Rome, it is too disjointed and digressive for that, but it intrigues. Who—the reader or Ritchie—was getting the correct version?

A Time In Rome is a period piece. Much of the writing is of quality as Bowen catches a mood of the city. There is a good description of the ceremony in St Peter’s in which the ageing Pope Pius XII beatifies Chinese Christians martyred in the Boxer Rebellion. ‘Half the lights in the world were already blazing, hanging in torrents from the roof, clustered against the carmine brocades clothing the columns, when on the ungated river of congregation we surged in, scaled to our places, waited’ as the pope processed among the frenzy of the crowds, ‘a scarlet spiked tree of gladioli’ carried before him. Yet there is a lot of Rome that she fails to catch, as if her mind never fully engaged with the city. I shall look out for the biographies—those by Victoria Glendinning (1977) and Neil Corcoran (2004)—and letters to find out why. I think she would have been happier in Florence.

Charles Freeman is the Historical Consultant to the Blue Guides. Bowen’s ‘A Time in Rome’ is one of works featured in Blue Guide Literary Companion Rome.