Top Paris food critic, Meg Zimbeck of parisbymouth.com, spent €7,000 of her own money to bring you uncompromised reviews of EVERY Michelin 3-starred restaurant in Paris, world centre of haute cuisine. And not only the nine 3-stars but also five 2-stars and one not yet rated. Read the Special Report (or just drool over the pictures) here »

Monthly Archives: February 2015

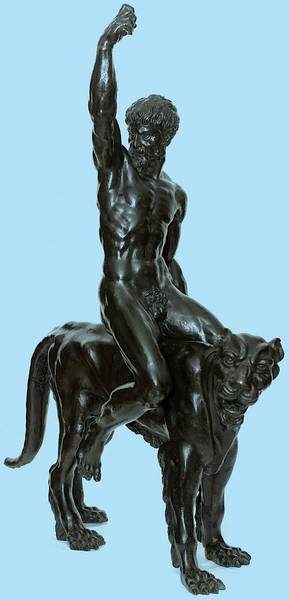

A Michelangelo discovery?

What a difference an attribution makes. I saw these two muscular nudes astride a pair of panthers in the Royal Academy exhibition Bronze in 2012 but remember other exhibits much more vividly. Now, however, they are the centre of attention in an exhibition in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, basking in glory following their recent attribution to Michelangelo.

Or is it recent? They were attributed to Michelangelo when they were exhibited in Paris in 1878. Perhaps some distant tradition clung to them when they were transferred from an aristocratic collection (possibly that of the Farnese family) to Baron Adolphe de Rothschild in the 1860s. The attribution was doubted at the time and the booklet A Michelangelo Discovery, which accompanies the Fitzwilliam exhibition, shows how difficult it is to date bronze. Since their first public appearance in 1878 experts have confidently put forward dates across the breadth of the 16th century and have linked them to specific artists. The curator of the 2012 exhibition placed them as only ‘within the circle of Michelangelo’, in the middle of the century, when of course Michelangelo was still active.

Then Paul Joannides, Professor in the History of Art at Cambridge, noted a copy of some lost drawings of Michelangelo in the Musée Faure in Montpellier, dated c. 1508, and there was a man astride a panther in very much the same pose as that of the bronzes. This clue to their origins—by Michelangelo himself but perhaps much earlier than thought—focused the research in new directions.

When one sees the bronzes they are larger than the photographs suggest, both just over 90cm, and then it is noted how one, the panther carrying the younger, clean-shaven man, is much more roughly cast than the panther carrying his bearded companion. Casting was always a demanding business, as readers of Cellini’s account of the casting of his Perseus in his Autobiography will know, and here some of the crispness of the modeling has been lost. There are signs that this bronze was hammered to remedy its deficiencies, a common practice when a complete recasting would have been unfeasible. There is a clue to the date in the casting itself. While the Classical sculptors had mastered the art of thin casts, the long-forgotten techniques and skills were only revived in the 16th century. These bronzes have thick walls, more typical of the early than the later 16th century.

Michelangelo is not normally associated with bronze and this may account for the hesitancy with which these casts were attributed to him. Yet there is ample documentary evidence that he used the medium, and lost bronzes of David and the papa terrible, Julius II, are known, both dating from the first decade of the 16th century. What confirms the attribution is the drawings of nudes, many of them in poses similar to those of the men on the panthers. An anatomical study of the relationship between the bodies and Michelangelo’s drawings, by Professor Peter Abrahams, notes the many congruences. Even the public hair of the bronzes. luxuriant for this period, closely matches that on Michelangelo’s great marble David in Florence.

The size of the bronzes is unusual. Life-size bronzes from this period include equestrian statues and Cellini’s Perseus in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence. More common are statuettes of both religious and mythical subjects and it is fitting that the Michelangelo bronzes help highlight the Fitzwilliam’s own fine collection of Renaissance bronzes. The size of the Rothschild bronzes falls between the two. Panthers are always associated with Dionysus, the Roman Bacchus, god of wine and disorder. A fine pair of panthers feature in Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (National Gallery, London), its date 1520–3, only a few years later than the proposed date for these bronzes. The nudes would therefore be bacchantes, Bacchus’ raucous companions. While they look far too healthy, perhaps even too well-ordered, for a life of dissolution, the authors note how the late 15th and early 16th centuries was an age of ‘serene, if short-lived classicizing culture. . .with its accent on refinement and dolcesse’, and this may explain their idealised forms. They appear to have been designed to be part of a larger display of a Bacchic celebration, perhaps in a frescoed palace interior or beside an antique statue of Bacchus himself.

First you have one pair of Renaissance bronzes and then you get another four. As I was writing this it was confirmed that the Victoria & Albert Museum had raised the £5 million needed to buy the four bronze angels that had originally been destined for the tomb of Cardinal Wolsey. Appropriated by Henry VIII for his own tomb when Wolsey fell, they were never put in place and their rediscovery, two of them on the gateposts of a golf club, was exciting. Wolsey commissioned them in 1524 from the Florentine sculptor Benedetto da Rovezzano who, in an intriguing coincidence, was the very man who finished the lost bronze David of Michelangelo noted above.

The well-illustrated A Michelangelo Discovery is a model text for those who want to know how an attribution is made. In fact if I was a professor of History of Art interviewing prospective students I would make them read it for discussion at interview. A fuller study will follow a conference on the bronzes to be held in Cambridge this summer, but so far everything—the manner of casting, the supporting pictorial evidence, the anatomical details, the cultural background—fits to confirm the attribution. This is a good time for aficionados of early Renaissance bronzes.

A Michelangelo Discovery: The Rothschild bronzes and the case for their proposed attribution, by Victoria Avery and Paul Joannides and other contributors, is published by the Fitzwilliam Museum. The (privately-owned) bronzes are on exhibition until 9th August and entry to see them in the Italian galleries is free.

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides. Freeman’s own book on four famous sculpted animals, not of bronze but gilded copper, The Horses of St Mark’s, is published by Overlook.

The Venus de Milo fights back

Jan Morris: Ciao, Carpaccio: An Infatuation

Pallas Athene, London, 2014.

The first time I found myself searching around in Carpaccio’s paintings was when I was writing my book on the Horses of St Mark’s. Had the Venetian Carpaccio ever used the horses as a model? An early match I got was the horse in the centre of his gruesome Martyrdom of the 10,000 at Ararat (Accademia, Venice), a depiction of the massacre of a Christian army by the Persians. The horse there faces forwards, has lifted his left front leg and turns his head in much the same way as the fine gilded copper steeds which were then overlooking the Piazza San Marco from the loggia of St Mark’s. Jan Morris goes further. She notes how actual horses had become rare in the city in Carpaccio’s day(he was active between 1490 and 1520). Sumptuary laws forbade extravagant harnessing; horses were banned from the Piazza and the new stepped bridges were difficult to negotiate. In compensation, Morris sees the St Mark’s horses everywhere in Carpaccio’s work, ‘all fine, every one of them, perhaps Carpaccio had modelled them all, if only subconsciously’ on the originals on the loggia.

Ciao Carpaccio is a delightful work of serendipity, ‘a self-indulgent caprice’ as the author puts it. Jan Morris does not claim to be a serious art historian but her eye is a lot more sensitive than many professionals and certainly, unlike some, she has the capacity to enthuse. Her book is all the better for revelling in what she sees and enjoys in Carpaccio’s paintings. And there is, of course, so much to see: the sumptuous clothing of his subjects, the intricacies of Venetian architecture and above all the meticulously observed details from everyday life. Too little is known about Carpaccio but he must have been fun to be with. He always has an eye for what’s going on at the edges of the formalities. Everywhere there are asides, vignettes of birds, playful children or beautifully-painted ships moored alongside some distant quay. Often Carpaccio’s love of display ensures that the subject of the painting is pushed completely to one side. So when the relic of the True Cross, encased then (as it still is) in the recently restored gold reliquary in the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista, draws forth the demon from a demented man, you can hardly see him high up on his loggia whereas below are the bustle of well-dressed crowds and some wonderful swaggering gondoliers in front of the early wooden Rialto bridge.

Carpaccio loves a parade. It is time for everyone to show off in extravagant hats, with plenty of music from trumpeters to add to the mood of excitement. He cannot avoid display, so that his Holy Family on the flight to Egypt would have been seen by any pursuer many miles off thanks to the typically Carpaccio bright red of Joseph’s cloak—and how did the Virgin manage to get hold of such a magnificent brocaded cloak for herself?

Yet Carpaccio is also a master of domesticity, as with Ursula’s well-ordered bedroom or the scholar’s study where Augustine works. Both, typically for Carpaccio, have dogs, a lapdog for Ursula and Morris’ ‘Carpaccio dog, a tough urchin mongrel, cocky, feisty and fun’ squirrelling around in Augustine’s study as our border terrier, Dipity, does in mine. And then on a shelf, among other antique curiosities of Augustine’s imagined 5th-century interior, is a small bronze horse, surely a copy of one from St Mark’s? All these works are beautifully reproduced, the illustrations taking up as much room as the text, so that Ciao Carpaccio makes a splendid small present for someone special.

Carpaccio was influenced by a popular text, the Golden Legend by Jacobo de Voragine, the must-have book for all those painting scenes from the lives of saints (Carpaccio drew from it for his magnificent sequence from the life of St Ursula, now in the Accademia). Ursula is destined for martyrdom along with the 11,000 virgins who accompany her, but it is almost as if menace is beyond Carpaccio. The Hun who is due to martyr her after she and her companions have disembarked at Cologne simply sits around looking bored. He certainly does not look as if he has it in him to massacre virgins. In another famous sequence, in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Carpaccio gently mocks the monks who are fleeing the friendly and somewhat mystified lion that arrives at their monastery with Jerome.

The paintings in this Scuola shows another influence on Carpaccio, the Orient, always in the minds of the venturesome Venetians but with added impact after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans some fifty years before. Many of his subjects—Jerome in Bethlehem, the proto-martyr Stephen in Jerusalem, St George triumphing over the dragon in Libya—are set in the East, and Carpaccio does his best to make this clear, using woodcuts of Jerusalem or an actual gateway in Cairo to provide a backing. There is even an obelisk in one of his depictions of St George.

Jan Morris concludes with a study of Carpaccio’s Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, now in the Brera in Milan. (Titian’s version is still in Venice, in the Accademia.) It is inspired by another ancient text, the Protoevangelium of James, that tells of the early life of Mary and how she was taken in to the Temple in the years before her betrothal to Joseph. The little girl kneels humbly on the steps while her parents stand proudly ‘like parents seeing off their child to summer camp or boarding school,’ as Morris engagingly puts it. But there is another child, a little boy shown with an antelope on a lead and a rabbit chatting to a priest leaning on the balcony of the temple. For Morris, this lad encapsulates the essence of Carpaccio, his quality of kindness. Perhaps it is because his sense of fun, a tenderness to his subjects and an unabashed love of colour for its own sake predominate that he is never numbered among the greats in art; but Jan Morris reminds us just how much pleasure he gives us, as he surely does for her.

See Ciao Carpaccio on amazon.com. See it on amazon.co.uk. For a more formal and wide-ranging treatment of Carpaccio’s work, see Patricia Fortini-Brown’s Venetian Narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio, Yale, 1988.

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides. Charles wrote the historical introduction to Blue Guide Venice.

Winter in Florence: a new look at Donatello

by Alta Macadam (author of Blue Guide Florence)

The wide streets around San Lorenzo, the great Medici church close to their family palace, which in effect form a piazza, have recently been cleared of market stalls so that the exterior of the building has regained its dignity. Inside visitors have been provided with a wonderful opportunity to come face to face with one of Donatello’s pulpits in the nave, now restored. An ingenious scaffold and lighting system has been set up so and if you put one euro into a little machine you can then climb up to the level of the pulpit and examine the details of the gilded reliefs. This is an occasion not to be missed, since the pulpits have always been very difficult to see, being raised up on columns. The pulpit in question is the one on the right, from which the Epistle was read, and the three reliefs at the height of the walkway are the Resurrection, the Ascension (or Christ Appearing to the Apostles) and the Descent into Limbo. Although Christ takes on a quite different appearance in each of the scenes, they were all cast together and they have a more or less continuous background. They date from the very end of Donatello’s long life, around 1460.

In the Resurrection Donatello famously portrays Christ as an anguished, elderly, infirm figure, hooded and still in his grave cloth, supported by his banner. In contrast (and following the familiar iconography of this scene), the soldiers in the foreground are depicted as genial innocents, most of them fast asleep but all in different attitudes, and with their feet carefully modelled. There is one seen from behind who seems to be hanging onto the edge of the tomb in astonishment, having just awakened; and if one looks even closer, there are two more in the far background on the other side of the sarcophagus: it is difficult to make out whether the scene includes six or seven soldiers. The frieze at the top of the pulpit has little playful putti and centaurs in relief around the central signature ‘Opus Donatelli Flo’ (the great sculptor was always touchingly proud of his birthplace), and at the corners are ‘classical’ horsemen, standing holding their horses’ bridles in a manner reminiscent of the Dioscuri.

In the Descent into Limbo Christ is still an elderly man but a much less dramatic figure: it is the scene itself which is particularly harrowing. On the extreme right stands the emaciated Baptist holding out his hand to Christ. All around, some half hidden, are the Saints who await liberation. But the crowd also includes figures without haloes: the head of Eve appears in the doorway and in front of her is Adam, with his arms stretched towards Christ. Two small grotesque devils, one entwined with a snake, and both with webbed feet, are also present. It has been suggested that the iconography of this panel may have been inspired by a miniature Byzantine mosaic which Donatello would have seen in the Baptistery (and which is today preserved in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

In the Ascension (or Christ Appearing to the Apostles) scholars have detected the intervention of Donatello’s assistants. Here a more genial Christ is shown in the act of blessing as cherubs help him on his slightly awkward upward journey, leaving behind the crowd of kneeling Apostles and the Virgin. They are seen behind a ‘fence’ which has ramblers on it and there are more roses and ferns on the ground at their feet.

The two end panels cannot be seen at such close range, but they are visible from the steps and are also wonderful works: the Marys at the Tomb and Pentecost. The Tomb scene is very dramatic, taking place as it does in a dark, underground burial crypt with a row of columns which partly obscure the sarcophagus, and one of which gives support to one of the Marys in her astonishment at seeing an angel blocking her way. Another Mary descends the steps but her face is totally hidden from view. A few trees can be seen outside in the background, above the roof. The Pentecost scene, although designed by Donatello, was executed in its final stages by pupils. The elderly Madonna is surrounded by the Apostles who have thrown their Crosses on the ground.

The other long side (which you can still only see from below, but which is now well illuminated) has two panels which are old replacements in wood, but the third is a very fine Martyrdom of St Lawrence, with smaller figures in a room portrayed in deep perspective. It is thought that Donatello worked on this panel before those on the other side, just after his return to Florence from Padua.

The pulpit opposite is still being restored and the idea is to move the scaffolding across to it also once the restoration is completed (probably in around a year’s time).

It is almost certain that the panels were not originally intended for pulpits but were made for a funerary monument or an altar in the church. One wonders if it might be thought legitimate to dismantle them once restoration is completed and display them in a way that they can be seen with ease.

The extraordinary genius of Donatello, so idiosyncratic in his iconography, can also be seen a few metres away in the Old Sacristy, beautifully kept and wonderfully illuminated. Donatello decorated this lovely little domed chapel (designed by Brunelleschi) some decades before he worked on the pulpits. And here on a cupboard is a terracotta bust of the young St Lawrence (or St Leonard?) one of the most charming Renaissance portraits which still mystifies art historians and which in situ is simply attributed to an unknown sculptor. One day perhaps it will join the catalogue of works by Donatello.

It is always somehow surprising that we cannot be sure of certain attributions, and that works which have been known about for centuries can sometimes be convincingly found to be by a master’s hand. This has happened recently to a terracotta relief of a Madonna and Child which belongs to the church of Santa Trinita and which in the early 19th century was moved by the Vallombrosan monks outside onto the campanile (presumably as ‘protection’ for the church). In 2004 it was brought back inside again (and replaced outside by a copy) and since it had been much ruined by the elements was sent to the restoration laboratory of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure. It revealed itself to be a very beautiful relief and is now attributed to Donatello himself (there are great similarities between it and a terracotta relief in Florida which is a recognised work of the master). At the same time an oval empty space (flanked by two painted angels) has been noticed inside the church in the niche above the tomb of Giuliano Davanzati and it has been agreed that the relief will be placed there when it returns to the church, in the belief that it must originally have been made for this position.

All this shows how work never ceases to protect and study the works of art in Florence and that restoration projects are carried on apace with all the skill and expertise we have come to expect from the state restoration laboratory here.