The impact of Kenneth Clark, the erudite patrician raconteur of the episodes of Civilisation, his majestic survey of European art first shown on the BBC in 1969, will always resonate with those who watched him. He adopted an unashamedly elitist approach that was delivered in a memorably clipped voice. ‘Civilisation’, he told us, was always precarious and would have been lost with the fall of the Roman empire if a few geniuses had not restored and kept it alive. It could be seen in exquisite buildings, great paintings and superb craftsmanship. Civility and rational thought acted as a backdrop to this fragile world distanced as it was from the toil and turmoil of everyday living.

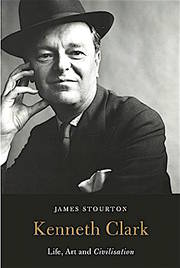

Of course, Clark’s approach was challenged, not least a few years later by John Berger in his Ways of Seeing, which looked far more critically at the way that art masked privilege and was used to maintain status. But when I listened again to one or two of Clark’s episodes (for the first time since 1969) I still found them absorbing. They drew me to this new biography of Clark by James Stourton, an accomplished art historian and former UK Chairman of Sotheby’s. I had enjoyed a retrospective of Clark’s life at Tate Britain in 2014 but had been disappointed by Meryle Secrest’s earlier life, which showed little understanding of the man and the world he lived in. This is a much more sophisticated and searching study.

Clark’s upbringing, as an only child on the large Suffolk estate of his fabulously wealthy parents, did much to shape him as a loner who developed a passion and sensitivity to art which provided him with the most enduring relationship of his life. He was lucky, while at Oxford, in securing the patronage of Charles Bell, the Keeper of Fine Art at the Ashmolean, who allowed him to explore freely the wonderful collection of Italian drawings. It was Bell who took him to Italy and introduced him at the age of 22 to Bernard Berenson, by now firmly ensconced at I Tatti, his villa outside Florence. Stourton suggests that it was within the Berensen ménage that, for the first time in his life, Clark found an emotional home. As their recently edited letters show, their relationship endured until Berenson’s death in 1959 but neither was able to establish a warm intimacy and a persistent undercurrent of rivalry pervades their correspondence. Clark’s first marriage, to Jane Martin, gave him his chance to escape Berenson’s tentacles and to embark on his glittering career back in England, working on the royal collection of Leonardo drawings, curating at the Ashmolean and directing the National Gallery through the challenges of the Second World War.

The Clarks became one of the must-have couples of the 1930s and their circle was wide. The relationship lasted but it had its bad moments, with Jane’s alcoholism and Kenneth’s affairs. The longest of these, with Janet Stone, lasted thirty years and the few extracts from their letters which have been published (most are still embargoed) show him at his frankest and most unbuttoned. Yet even here there would be limits. He failed to marry Janet when both were free to do so and in a melancholy aside Stourton tells how many of her letters to him were discovered still unopened. It is hardly surprising that Clark remained an enigma to most of his acquaintances. He often spoke of himself as a fraud, as if there was some appalling secret about him about to be revealed. There was a gulf between how accessible he wanted to be to others and the distance that they usually encountered as they tried to get close. There was another between his glittering lifestyle, his castle at Saltwood, and his adventurous purchases of art, and his claim to be a socialist at heart.

Even so, Clark’s expertise and extensive address book kept him going from post to post. He was always much more than a social butterfly. His patronage of important artists such as Henry Moore and John Piper were crucial for their success. He showed, through a love of Japanese art, of Aubrey Beardsley, alongside that of his contemporaries, that he could break free of the rarefied world of Renaissance drawings. He took on roles that seemed far from any of his interests. To become Chairman of the Independent Television Authority when he did not own a television set and when ITA was seen as the harbinger of a collapse in cultural standards appears more than public duty demanded.

Stourton deals well with the making of Civilisation. He has tracked down some of the original film crew and interviewed the widow of the director, Michael Gill. Gill appeared to represent everything that Clark most despised. As his widow remembered, the couple did not fear that the barbarians were at the gate, Gill would have actually liked to be one of the barbarians. The relationship between Clark, Gill and the third director, Peter Montagnon, eventually developed into a creative one and the series turned out to be an extraordinary success, especially in the United States. It is what ‘Lord Clark of Civilisation’ is remembered for.

It may be that Clark’s life and times are now too remote for this book to be a bestseller (his son Alan made a more recent éclat with his gossipy diaries) but this was a biography that deserved to be written and it has been exceptionally well done. Until the full range of Clark’s letters to Janet Stone are revealed it will be as definitive a life as we could wish for. It may even take some of us back to important books of Clark’s such as The Nude, a groundbreaking study, or his Leonardo da Vinci, still regarded as one of the finest explorations of this genius and praised by Stourton as such.

Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Civilisation, by James Stourton. William Collins, London, 2016. Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides.