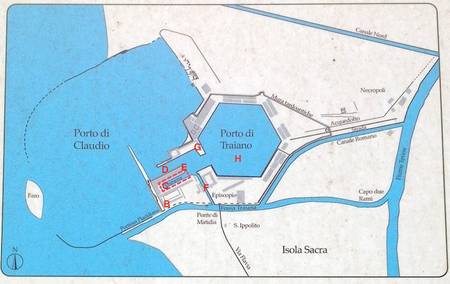

We were lucky to get into the area of the old Port of Trajan, just south of Fiumicino airport. The website states that it is “open” between 9am and 1pm on the first Saturday and last Sunday of the month, and gives a Google map with a pin stuck in it close to the Parco Leonardo railway station. So we took a train there, on the first Saturday of the month, and arrived shortly after nine thirty. No museum in sight. I rang the number and was told that the guided tour had already begun, that there was no way we could join, that in any case a prior booking was necessary. We could come back on the last Sunday of the month. “No,” I said, “you don’t understand. I’ve NEVER been in Rome on the right day of the month before. This time I am! It’s my only chance! We really want to join the group. Tell us where they are!” We set off on foot, along the busy Via Portuense, with the prospect of several kilometres to go, narrowly missing being flattened by trucks. Then a godsend: a man stopped and gave us a lift. The entrance gate was just under a motorway flyover (marked A on the map). By extraordinary good fortune, the tour was just inside the gate, inspecting the remains of what had once been a portico fronting a line of granaries belonging to the old Port of Claudius.

The ports were laid out here in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, first by Claudius and then by Trajan. The sea has retreated some three or so kilometres west since then, and most of the area has dried out or been drained, but some of the old contours remain. The grain stores, though overgrown with weeds, still clearly retain parts of their old flooring, built up on brick stilts known as suspensurae, a device designed to minimise damp.

Claudius’ port was, in its heyday, the largest in the Mediterranean, with 800m of wharf. But it was unsheltered and very vulnerable to storms. In AD 62, for example, 200 ships at anchor were wrecked in a gale. The complex was altered, with a new harbour further inland, by Trajan. We left the Claudian area by means of a short colonnaded street (B), with a double enfilade of chubby travertine columns running up it. On one side we were shown a brick archway filled in with bricks arranged in the crosswise opus reticulatum pattern. The archway was never open, the guide explained. It was placed there to give greater strength, to direct the downward thrust of the wall outward to the buttressing piers on either side, at a point where there is no stable ground directly underneath. We were also shown two pieces of fallen travertine column. One of them, a capital, had two iron pegs sticking out of its underside. It was with these that the capital was fixed to the block below it, but with a “glue” of molten lead, which was poured in along specially cut runnels (shown in the next illustration). Lead, unlike iron, has a certain amount of elasticity, which can better withstand seismic shocks.

Load-distributing arch

Capital with iron fixing pegs

Block with square hole for fixing peg and runnel for molten lead

View of the colonnaded street

At the end of the colonnaded street we turned right, to the site of the old Darsena, Trajan’s inner harbour (C). There is little to see now but a reed-filled marsh, but at one side the stone harbour wall can be seen. Analysis of the warehouses that stood alongside this harbour has shown that the stores of marble, the heaviest item to move, were—perfectly logically—placed closest to the dock. On the further side were warehouses that had possibly held grain, or some other commodity sensitive to damp, since the walls had been coated in a layer of pozzolana, a waterproof cement made from a mixture of lime and volcanic ash.

From here we walked out onto a broad, flat path, grass-grown now—though once it had been filled with water, for this was the channel (D) that linked the old Port of Claudius with the hexagonal Port of Trajan. It is wide enough for several ships to have passed along it at once. At its far end we could see the remains of large warehouses (E). We turned past them, onto a narrower path (F), again once a water channel linking the harbour complex with the Fossa Traiana, the canal that Trajan dug to link his port to the Tiber.

We were all impatient to see the famous hexagonal port, but there was wildlife to be admired: a herd of fallow deer; enormous funghi that were erupting from the soil practically before our eyes; a long black-and-yellow chequered snake; and scatterings of porcupine quills. The land is a bit unkempt. Much of it belongs to the Torlonia family. It could be a magnificent park, if time, energy, money and enthusiasm could be found…

Part of the hexagonal basin is flanked by warehouses of the Severan period, probably built during the reign of Antoninus Pius. It was possible to climb onto a sort of viewing platform, to get a glimpse of the basin (G). But the view from the ground is nothing compared to the sight of it that you have from the air, when flying from Fiumicino. This huge six-sided harbour has always been full of water. In the Middle Ages it was stocked with fish. No one is sure why a hexagonal shape was chosen. The information board at the site was non-committal. Our guide was keener on the more interesting story: that it was the work of the great genius Apollodorus of Damascus, the architect who designed the Markets of Trajan in the Imperial Fora. That he chose a hexagon because the ripples caused by ships moving into it would create “echo-waves” coming from the side, which would meet the outgoing wave and effectively cancel it out. We experimented with this at home, with a six-sided container but, sadly, managed to prove nothing. The tour was long, but very interesting. Today, as Blue Guide Rome so aptly puts it, most overseas traffic to Rome still docks here: the airport of Fiumicino could not be located in a more appropriate spot.

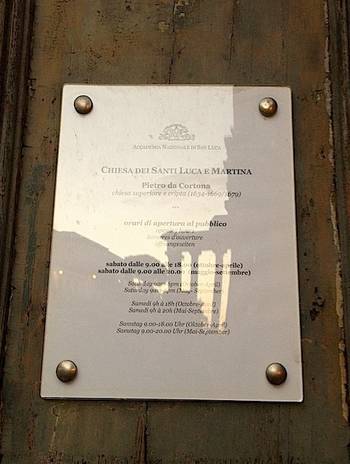

Information for visitors:

Open on the first Saturday and last Sunday of the month. Call ahead to book: T: 06 6529192. Meet at the Museo delle Navi, Via A. Guidoni 35 (Fiumicino Airport). Tours begin at 9:30 and last approximately three hours.

For updates on the ongoing archaeological project of the British School at Rome/University of Southampton, see here.