Some suggestions from Blue Guides’ historical consultant Charles Freeman

I haven’t been to Istanbul for some years, so it is good to be going back at last, to set up a tour I shall be leading in October. Of course, I shall be keen to put the new Blue Guide to Istanbul to the test and I have already been browsing. John Freely has alerted me to several smaller mosques that I have never visited so my appetite is already whetted. All my group will have their copies of the Guide but I need to offer them other recommendations.

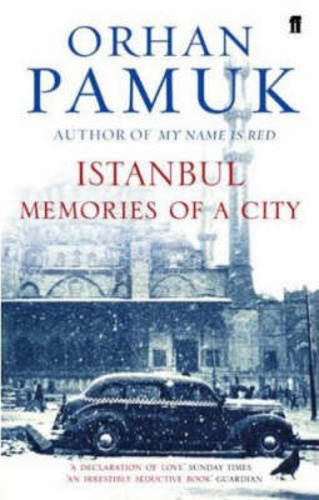

I was depressed by Orhan Pamuk’s novel Snow, which I read last summer, but have preserved much warmer memories of his Istanbul, Memories of a City, a bittersweet account of his growing up in the city in the 1960s and 1970s (Faber, 2005). Pamuk brilliantly describes the complex and brooding relationships of a family that is trapped between traditional life and the pseudo-western alternative that is replacing it. He mourns the wooden buildings of the old town but in his adolescence he gradually found his own way into the complex and transient cultures that were being erased. So here too is an introduction to the literature of the city, the writers who visited it with their preconceptions and desires. Over the city, for Pamuk, rests huzun, a blanket of melancholia, heavy with the memories of those who have passed through. Has anyone really found a permanent home in a city of such transience? Pamuk suggests not. This haunting and beautifully-written book will certainly be on the list.

Recently out is Peter Clark’s Istanbul, A Cultural History in The Cities of the Imagination series (Signal Books, Oxford, 2010). Clark has never lived in Istanbul but he has family there and a long experience of viewing, as a British Council employee, its impact as the capital of the empire on its former provinces. He has amassed a large repertoire of stories and impressions, of his and others, and writes with a pleasing style. The bulk of the book comes after the Ottoman conquest of 1453; only 45 pages are on the Byzantine Empire and much of this on the empire rather than the city (although this could be justified by his title). As the book continues, it gradually becomes more of an anthology, a pastiche of the stories Clark has picked up in his wide reading or gleaned from his wanderings in the city. While never dull, it really needed to be brought into better order. Chapter Four, on the nineteenth century, jumped from subject to subject, often without any relationship between them. Another chapter is a wander through Belle Epoque Istanbul. I would happily sign Peter Clark as a real guide here but in print, and with few illustrations, the details of each building overwhelm. The chapter ‘Sailing to Istanbul’ is simply a series of vignettes of nineteenth-century travellers who left some memories of their visits. With good editing, however, there is a valuable second edition waiting to emerge from the present text.

So I have gone back to rereading Philip Mansel’s superb Constantinople: City of the World’s Desire, 1453–1924 (John Murray, 1995). I finished it the first time as I was on a boat going up the Bosphorus in the late 1990s and found it magnificently detailed and absorbing. It brilliantly captures the atmosphere and tensions of the city. Much of my work on Istanbul is on its Christian Byzantine past and I have forgotten most of what I learned about the sultans the first time around, so it will be a treat to meet them again in Mansel’s vivid account. He reminds us too just how much Istanbul was part of a wider Mediterranean commercial and political world in the nineteenth century as the European powers tried to fit it into their strategic plans. It remains a great and relevant read nearly twenty years on and so will certainly be on my recommendations list.