I have always been fascinated by circular buildings. The Pantheon and Santa Costanza in Rome, the tholos at Delphi. One of my especial favourites is the little-visited Santo Stefano Rotondo, on the slopes of Rome’s Caelian Hill. Below is an extract from the Blue Guide travel monograph Pilgrim’s Rome:

Santo Stefano Rotondo

Open Tues–Sat 9.30–12.30 & 2–5.

In AD 64, during the reign of Nero, a great fire consumed central Rome. It was witnessed by the emperor from a tower on the Esquiline Hill. After the flames had done their worst, Nero instigated a full-scale witch-hunt of the city’s Christians: St Peter may have died at this time. Nero then expropriated the land in the valley between the Esquiline and Palatine hills and constructed his vast Domus Aurea, or Golden House, a sumptuous gilded pleasure palace whose grounds incuded a vast artificial lake (where the Colosseum stands now). To feed this lake, water was brought by a new aqueduct, parts of which can still be seen around St John Lateran and here on the Caelian Hill, in the gardens of Villa Celimontana. To get to the church of Santo Stefano Rotondo, you must pass beneath one of its archways.

Santo Stefano Rotondo is a fascinating and atmospheric building, secretive and little-visited, is one of the finest surviving Roman examples of a circular mausoleum-church. It richly rewards any effort made to seek it out.

The association of a circular design with funeral architecture is very old, going back to the ancient Greeks and the Etruscans. Imperial-era Rome made use of it too: the circular mausolea of Augustus and Hadrian still exist, one on each side of the Tiber bank. It is no surprise, then, that the tradition was also adopted by Christians. But just as Christian churches are congregational—unlike pagan temples, where access was restricted only to an elect college of priests—so Christian mausolea were also designed to accommodate crowds of the faithful. The mausolea of Augustus and Hadrian are mainly solid, with just a narrow tunnel and sepulchral chamber inside. There is no internal volume. Christian mausolea enclosed a wide open space designed to allow worshippers to process around and pay homage to the tomb within. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, built by Constantine around the tomb of Jesus, is the most famous example of such a structure. In Rome there is the partially collapsed mausoleum of St Helen, Constantine’s mother; the mausoleum of her grand-daughter Constantia (the church of Santa Costanza); and this church, Santo Stefano Rotondo.

Santo Stefano dates from the late fifth century and is dedicated to the first Christian martyr, St Stephen. In the late sixteenth century the walls were decorated with scenes of the whole panoply of Christian martyrdom, beginning with the Massacre of the Innocents and the Passion of Christ and from there progressing through all the martyred saints, from Peter and Paul during the reign of Nero, through all the gory deaths died under subsequent imperial persecutors and ending with a final scene showing a row of triumphant saints resurrected in peace and glory from the scenes of earthly carnage behind them.

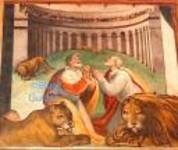

The chapel on the left as you enter the church is dedicated to two Roman brothers, Primus and Felicianus, both martyred under Diocletian and buried in the old sandpits (arenaria) beside the Via Nomentana. Their remains were transferred here in the seventh century, from which time the chapel mosaics date. In the apse, the two saints are shown on either side of a jewelled cross with Christ in a roundel above it (not Christ crucified; early attitudes to crucifixion are dealt with elsewhere in the book). The sixteenth-century frescoes (illustrated) show the two brothers exposed to lions and bears in the arena before being gruesomely done to death.

Below the church is a Mithraeum belonging to the Castra Peregrina barracks (the cult of Mithras is explained elsewhere in the book).

Text © Blue Guides/A.B. Barber