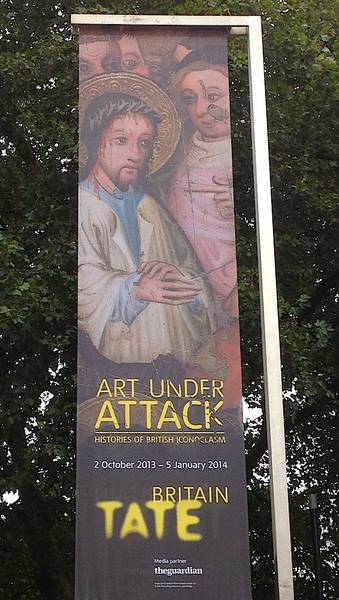

Reviewers of this exhibition (Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm, running at Tate Britain until 5th January) have fretted about whether what it presents is or isn’t true ‘iconoclasm’. I don’t think it matters. The curators make it clear from the outset, on the wall caption that greets you before you even enter the first room: they know full well what true iconoclasm is: it was the fuss that began in 8th-century Constantinople when Leo III ordered the destruction of the icon of Christ which hung over the Bronze Gate. That is one thing. But today we use the word much more loosely, to mean simply ‘breaking the mould’. Of course this can be approached with a responsible intellectual purpose, to question and to elicit answers. Or it can be approached frivolously, for the sheer mischievous hell-raising fun of it, to give the poor old bourgeoisie a fit of the vapours. Iconoclasm can equally be used to mean just ‘not doing things the way they’ve always been done’. Refusing to serve Yorkshire pudding with roast beef might be enough to qualify a chef as an ‘iconoclast’. All these things form part of the exhibition’s trail through the history of how works of art in Britain have been attacked, mutilated or otherwise tampered with, and the variety of motives behind it.‘The Risen Christ’ panel from Binham Priory. Figure of Christ painted c.1500; overlaid text c.1539.

The first rooms deal with iconoclasm in the original sense of the word: the destruction of religious images deemed idolatrous. The scope of the exhibition does not reach beyond Britain, so we begin with Henry VIII. Whatever one thinks about it—is it sacrilege? Is it unpardonable destruction of lovely works of human hand?—it is tempting to conclude from this display that the reformers carried out a principled operation. They wanted to make it impossible to adore the painted or graven visage, so they scratched out the faces and chopped off the heads. They wanted to replace the visual pictogram of God-as-icon with the appeal to the intellect of God-as-the-Word, newly available in English translation for all to understand. A panel from the famous rood screen from Binham Priory, Norfolk, illustrates this superbly: an image of the Risen Christ was whitewashed over and replaced with text from Cranmer’s Bible. Now the whitewash is flaking away and we can see the coloured icon underneath. But the reformers didn’t indulge in wanton destruction. By the time Cromwell comes on the scene, though, a thuggish element has emerged. We read stories of stained-glass windows being taken down for zealous prelates to trample to smithereens in public acts of toeing the new line. Politics have surged on stage and personal agendas are coming to the fore: the prelates want preferment; they want to curry favour with the new ruling elite. Not only is there a kind of glee behind the smashing and hacking, but a feeling of calculation.

This is one face of political iconoclasm. But in the next room we see another: iconoclasm as a form of mass protest. An equestrian statue of the monarch is daubed in spots to make it ridiculous and impossible to respect; a pillar with Nelson on top of it is blown to smithereens in Ireland. We’ve not seen this before. Up until now, icon-smashing has taken place by official diktat (as the iconoclasm of Communism was later to do); it has been iconoclasm as political repression, the smashing of other people’s totems as a form of intimidation and a symbol of who calls the shots. Now we see icon-smashing as a vehicle for the people’s voice.

What comes next is what the curators have termed ‘aesthetic iconoclasm’: tampering with works of art (or craftsmanship) in order to make a ‘statement’. Artists traditionally have striven to make coherence out of chaos: the avant garde practitioners whose (often paltry) efforts we are shown here seem to be doing their best to make chaos out of what had once been order: the burst-apart chair; the disembowelled piano. What does this say about the psyche of the 20th century? One thing it says is that these are personal affirmations. This kind of icon-breaking is carried out neither by governments nor by the masses but by individuals, who in some cases are simply mutilating things that they don’t happen to like. The display throws up plenty of questions for our pluralistic age. How are we to tolerate each other with no central control of what we believe in or approve of? Do we even have universally recognised icons any more? Is it OK to throw a can of paint over the result of someone else’s freedom of expression because personally we find it ‘offensive’? Do artists have a responsibility to society? And if so, what is it?

The exhibition doesn’t answer these questions. But they are valid questions to have asked. The best thing in the last part of the show is Douglas Gordon’s burned poster of Warhol’s screen prints of Queen Elizabeth II. For this is destruction of a twofold icon: a Warhol work of art and Her Majesty the Queen, a beautiful young monarch. And here the exhibition comes full circle. We are back to the Virgin Mary, to an image of a reverend figure insulted and abused. Gordon himself described his work as ‘homage to Warhol and an act of desecration’.

The exhibition itself, in a way, leads us from order into chaos. It functions as a microcosm of what iconoclasm does when it takes a hammer to a work of art. The clarity of the narrative begins to waver after the first rooms, with their impeccable presentation of historical iconoclasm, through the turmoil of the political rooms to the utter muddle of the aesthetic rooms—but we live in a muddled age, so the progression works. It mirrors humanity’s own progression from a world of centrally-imposed certainties to one of democratically enhanced confusion. In the room that deals with the suffragettes’ attacks on works of art, we learn all about Mary Richardson and her butchery of the Rokeby Venus: she swung her knife at a beautiful painted woman in protest at the way Emmeline Pankhurst, ‘a beautiful living woman’, was being treated in prison. There is a lovely irony in this. Because of course the Rokeby Venus presents us with the ultimate iconodule or worshipper of icons: Venus gazes at herself in a looking glass: this is a goddess adoring her own image. Mary Richardson may not have thought of that. Wyndham Lewis’s response in Blast, which the exhibition is careful to remind us of, was patronising, perhaps, but apt: ‘Leave art alone, brave Comrades! In destruction, as in other things, stick to what you understand.’