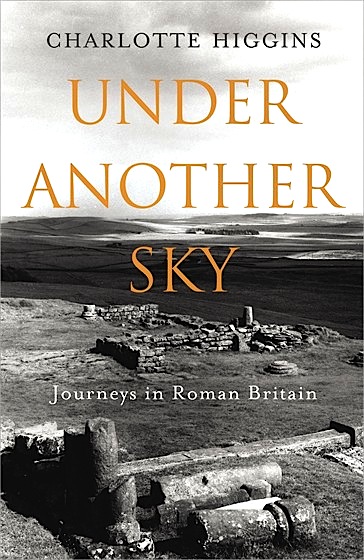

Charlotte Higgins, Under Another Sky: Travels in Roman Britain. Jonathan Cape, London, 2013. Reviewed by Charles Freeman.

If I am heading westwards from my home in central Suffolk I go along a stretch of Roman road and eventually reach the village of Stonham Aspal. To the far side there is a ridge overlooking open countryside and it is here that a Roman bathhouse was discovered in 1962, when building work was being done for some bungalows. It was my first dig, with a tolerant Ipswich Museum team interpreting laws against child labour generously enough to allow a fourteen-year-old to shovel out ashes from a Roman hypocaust. The main part of the villa is assumed to have been on the other side of the road and remains unexcavated, but I still tell the story to anyone I am driving that way.

The pottery from the site is of the 3rd and 4th centuries, the greatest period of the British Roman villa. This was the time of prosperity before the collapse of Roman rule in the early 5th century brought a devastating fall in living standards (apparently as a dramatic as anywhere else in the western empire). Looking back, I wonder what the ashes I scraped out could have told of the final fires lit to heat the baths. There was no one on hand to record the last days of the empire in Britain but gradually the cities, already faltering in the 4th century, were abandoned and the great buildings fell in or were buried. One of the most evocative finds has been a luxurious Roman villa on the London waterfront that enjoyed a heyday in the 3rd century but then began to crumble, although 200 coins dated as late as ad 388 talk of a late burst of occupation.

Charlotte Higgins’s delightful book is an account of her searches for Roman Britain in the company of her boyfriend Matthew and a venerable and resilient camper van. Higgins read Classics at Oxford so she knows her sources—predominantly those of the finest Roman historian—Tacitus, and she weaves them gently into her itineraries. She has also absorbed those who have been before her: William Camden, the author of Britannia (1586), the first quasi- scientific study of British antiquities, and the polymath William Stukeley (1687–1765), who recorded what stood of Silchester, Hadrian’s Wall and other sites. Stukeley, a fan of the Druids, was sadly taken in by a fake history of Roman Britain purporting to have been written by one Richard of Westminster in the 14th century. Stukeley’s enthusiastic support for it meant that it was treated as authentic and Roman history distorted until well into the 19th century. The Pennine chain of hills take their name from the pseudo-Richard’s description of them.

Gradually out of these forays into a misty past, archaeologists took over. So here is Mortimer Wheeler and his much put-upon wife Tessa, bringing military precision to excavations of St. Albans and later, and most famously, of the Iron Age fort of Maiden Castle. Wheeler revelled in describing the last stand of the British against Roman onslaughts and the mass grave into which the defeated British were thrown. Unfortunately, more recent work queries whether the cemetery was ever a mass grave at all; but the story gripped me as a teenager. By the 1970s, we arrive at more delicate work, especially with the writing ‘tablets’, actually slivers of wood, from the Roman fort at Vindolanda, miraculously preserved in waterlogged ground. Excavated by Robin Birley and deciphered by Alan Bowman, they provide an astonishingly graphic account of everyday life on the frontiers at the end of the 1st century ad, as invites go out for birthday parties and details of which men are available for outside work are painstakingly extracted from the intricate lettering.

Higgins also ventures further north to discover reminders of the short-lived invasion of Scotland by Agricola in ad 79 or 80 (we know of it because the historian Tacitus was Agricola’s son-in-law and left a vivid account) and the little-known Antonine Wall, held only briefly before the frontier was pulled back again to the better-known barrier built by Hadrian. She takes in Bath and York, the latter achieving an empire-wide status when the emperor Septimius Severus established his court here between 208 and 211 and when, a century later Constantine, the first Christian emperor, was proclaimed emperor by his father’s troops. In Bath the Romans adopted the local Celtic god Sulis, associated her with their own Minerva, and the temple dedicated to both presided over the hot springs that were to set Bath up as a watering place in later centuries. In Colchester and London, dark layers record the burning of the nascent Roman settlements by the furious Boudica, in a devastating but ultimately crushed campaign (ad 60 or 61) that also survives in Tacitus’ account.

I am sorry that the camper van, with ‘its many and varied complaints’, did not merit an entry in the index. I would have liked to have retraced its valiant hill climbs even if it did collapse in York and thus not quite make it to Hardknott Castle (a 2nd-century fort guarding Hardknott Pass), perhaps the most spectacular of all the Roman sites in Britain. It added character to what is an engaging survey of our Roman past. While Higgins records exhaustive studies of Roman Britain (Roger Wilson’s A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain and the mammoth four-volume compilation of every known Roman mosaic by David Neal and Stephen Cosh), she provides a more light-hearted account, a valuable reminder of how the Roman past lies not too far beneath our feet. Indeed a metal detector unearthed a worn Roman coin from our own fields just a year ago, and, this being Suffolk, perhaps another Mildenhall treasure, the hoard of astonishing silver plate unearthed in 1942, is just waiting to be discovered close by.

Under Another Sky was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Non-Fiction Book of the Year Award.