The Portofino peninsula today is a regional park, visited for its stunning views, the special flora and fauna and the microclimate, not to mention the extraordinary geology. It has been, however, for a much longer time a strategic outpost. On a clear winter day one has an unimpeded view stretching from La Spezia to Capo Mele with, in the middle, in the distance, a faint notion of Corsica. The Genoa archives have thick bundles of documents relating to the military use of the location way back in the 18th century. Today’s hikers, though, will not have failed to notice military remains, thick cement constructions, looking decisively much more recent. These are almost undocumented: nothing in the archives, neither in Genoa nor in Germany. But they are indeed a combined Italian and German effort going back to WW2.

In 1939 the Italian army proceeded to install three guns on the west side of the peninsula in a place known as Erbaio, just above Punta Chiappa. Three concrete platforms were built for the purpose and three guns intended to protect Genoa harbour were installed. They were 6m long, 152/20mm calibre with a 10/15km range. In the autumn of 1943, the German army took over the coastal defences. Beaches were blocked and mined and the German Marine Artillery Command 619 organised a number of batteries in the area: Monte di Portofino was one of them. They were manned by German troops assisted by elements of the Todt Division (Italian civilians doing military work) and some locals.

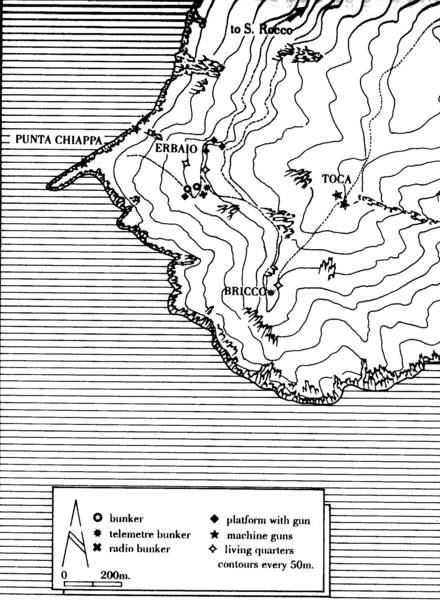

A number of batteries were added and were connected by the very same paths that today’s hikers use, all leading to S. Rocco, the location of the German headquarters in the beautiful villa Giulia (see plan). At sea level Punta Chiappa, the only sea access, was defended by three machine gun station not far from the harbour where the vaporetto delivers its cargo of visitors in summer. Higher up at Erbaio (the path connecting the two locations was better in those days) the existing complex was enlarged with three sentry posts, headquarters, dorms, an infirmary, stores and kitchen, washroom and toilets, and even an open-air altar built in a stone that is not local and painted blue. Huge concrete bunkers (wall thickness 2m, roof thickness 3m) were built to cover two of three guns previously installed by the Italian army. They were grassed over for camouflage. Two smaller concrete constructions (radio bunker and telemetre, i.e. observation bunker) connected by a spiral staircase in the rock were built nearby; camouflage was by hooking nets covered in suitable vegetation. More tunnels were blasted out of the rock to connect the installations and provide ammunition storage. A large graffito warned soldiers not to play with the guns because they might be loaded. There was also room for four additional machine guns. The surroundings were mined.

From Erbaio the Germans built a path to Bricco, a location that affords the best possible panorama of the Gulf of Genoa, and built another observation bunker with tiny living quarters nearby. Fixed machine guns were installed high up at Toca (which is where Semaforo Nuovo is) and at Base O just off the coastal path from San Fruttuoso to Portofino (just look at it, do not try to go there: it is too dangerous).

Erbaio (and probably Bricco as well) had electricity from the generator in the headquarters. Water came via an aqueduct tapping a source higher up. All the plumbing had disappeared by 1947 but the tunnels in which it ran are still there.

Was it all worthwhile? Certainly the effort involved in the enterprise was considerable: everything was hauled up from sea level. The Germans clearly felt that the three big Italian guns would not be sufficient to protect the port of Genoa, foil a possible Allied landing and protect traffic. In those days the bombing of the railways and the submarines lurking in the depths meant that a lot of goods were moved by rafts hugging the coast. But in the end, it did not make a scrap of difference. That already became clear in 1941 when a submarine sunk a merchant ship, the Ischia, under their very noses just off Punta Chiappa. Genoa harbour was repeatedly bombed. The three big guns never fired a single shot and vast quantities of ammunition were found, unused, stacked in the tunnels at the end of the war. As legend has it, relations with the locals were pretty good. The Germans—some 70 of them—were allowed to leave unmolested at the end of the war. Some even maintain that the commandant married a local girl, one of the 40 or so civilians that commuted daily from S Rocco or Punta Chiappa to do the cooking, the laundry and other menial jobs. That’s possibly stretching it a bit. But they certainly went home with a fabulous tan.

by Paola Pugsley, author of Blue Guide Crete and three e-chapters on Turkey. The Portofino peninsula and San Fruttuoso are covered in the Blue Guide e-chapter on Liguria, by Paul Blanchard.