Blue Guide Lombardy, Milan and the Italian Lakes is timetabled to appear at the end of this year. Here are some images from a recent research trip to Lake Maggiore.

The castle of Angera looms tall over the southern end of the lake. In the possession of the Borromeo family since the mid-15th century, it was once one of a pair of fortresses with the Rocca at Arona, on the opposite shore. Together they controlled the lake. Ferries connect the two towns. The Angera castle is open to visitors from March to October. The castle of Arona was destroyed by Napoleonic troops in 1800.

Arona’s castle may be no more but this town, with its pleasant waterfront, is a good place to see art in situ. The church of Santa Maria Nascente has a lovely early work (1511) by the native artist Gaudenzio Ferrari. The central panel of the Nativity is illustrated here (above left). Further up the lake in Cannobio is another, later altarpiece by Ferrari, of the Way to Calvary (illustrated above right).

The islands are one of Lake Maggiore’s most famous attractions. Isola Bella (illustrated above left) was laid out for Carlo III Borromeo over a period of 40 years (1631–71), with tiers of terraces built out onto the lake and filled with imported soil and exotic plants (as well as white peacocks). At night they are illuminated and form a truly extraordinary sight. The island, still owned by the Borromeo family, is open to visitors between late March and late October.

Isola dei Pescatori (illustrated right), once occupied by a hamlet of fishermen, is now mainly given over to tourism. It is extremely pretty from the water, accessible by regular boats, and offers some good places for lunch.

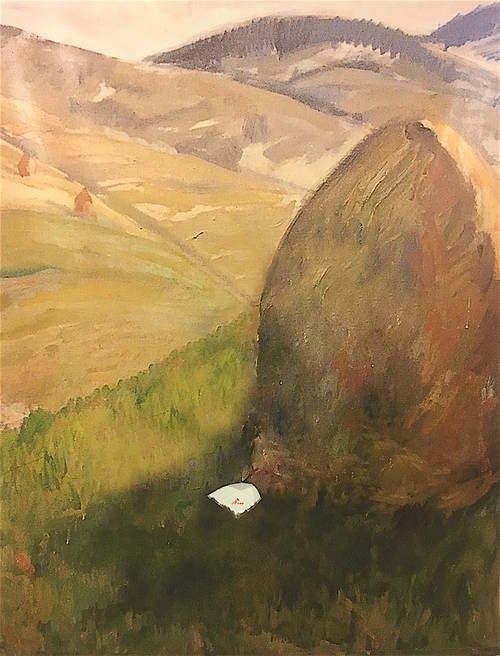

From the little town of Stresa, a cablecar takes you to the top of Mt Mottarone (1491m) via Alpino, where there is a botanic garden. The trip is highly recommended. The views from the summit are genuinely magnificent. On a clear day you can see a total of seven lakes. On hazy days, you are treated to a vista of layered mountain peaks.

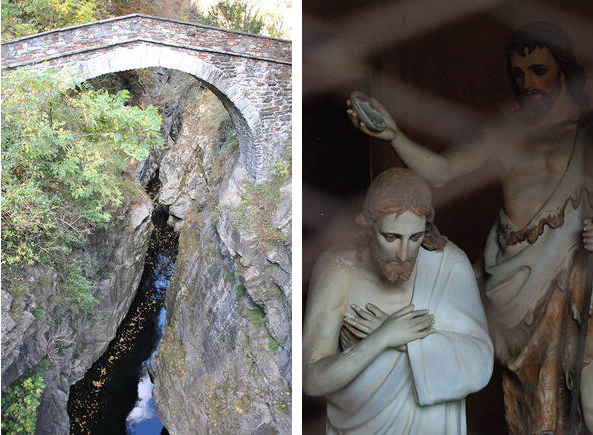

Natural and man-made attractions around the lake include the deep and narrow gorge of the Orrido di Sant’Anna, behind Cannobio, crossed by a tiny hump-backed bridge and offering an excellent place to have lunch; and one of the loveliest of the famous ‘Holy Mountains’ of Piedmont, a cluster of chapels and shrines above Ghiffa. The ‘Sacri Monti’ were conceived during the period of the Counter-Reformation, as bastions of the Catholic faith as well as places for pilgrimage and meditation. The shrines and chapels typically house lively statue groups in painted terracotta. Illustrated here is the Baptism of Christ (1659), a composition made all the more effective by the fact that you can only glimpse it through a grille. The vivid blue eyes of Christ shine luminously in the semi-dark.

Pallanza, the west-facing part of Verbania, the largest town on the lake, is home, on its headland, to the famous Villa Taranto, with famous botanical gardens laid out by a retired Scottish army captain, Neil McEacharn (for more on him and his story, see here.

Many of the lakeside towns are graced with grand hotels and villas from the great age of northern European resort tourism in the 19th century. The Grand Hotel des Iles Borromées in Stresa opened in 1863 and has had many famous guests during the course of its existence, both in fact and in fiction (Ernest Hemingway uses it in A Farewell to Arms). Contemporary architecture has given Verbania the ‘Il Maggiore’ concert hall and events space (Salvador Pérez Arroyo, 2016).