The poet John Keats died of tuberculosis in Rome, in February 1821: two hundred years ago exactly. The apartment on the Spanish Steps that he had rented with his friend, the struggling painter Joseph Severn (who nursed him faithfully to the end), is now the Keats-Shelley Museum. The Life and Letters of John Keats, by Lord Houghton (1867), contains a moving account of the poet’s last days, including letters written by Keats and Severn. The following is probably the last letter that Keats wrote:

Rome, 30th November, 1820

My dear Brown, ’Tis the most difficult thing in the world to me to write a letter. My stomach continues so bad, that I feel it worse on opening any book,—yet I am much better than I was in Quarantine. Then I am afraid to encounter the proing and coning of any thing interesting to me in England. I have an habitual feeling of my real life having passed, and that I am leading a posthumous existence…I cannot answer anything in your letter, which followed me from Naples to Rome, because I am afraid to look it over again. I am so weak (in mind) that I cannot bear the sight of any handwriting of a friend I love so much as I do you. Yet I ride the little horse,—and, at my worst, even in Quarantine, summoned up more puns, in a sort of desperation, in one week than in any year of my life…Dr Clark is very attentive to me; he says, there is very little the matter with my lungs, but my stomach, he says, is very bad. I am well disappointed in hearing good news from George—for it runs in my head we shall all die young…Severn is very well, though he leads so dull a life with me. Remember me to all friends, and tell Haslam I should not have left London without taking leave of him, but from being so low in body and mind. Write to George as soon as you receive this, and tell him how I am, as far as you can guess;—and also a note to my sister—who walks about my imagination like a ghost. I can scarcely bid you good bye, even in a letter. I always made an awkward bow. God bless you! John Keats

Keats’ condition continued to deteriorate. Two months into the new year, on 15th January 1821, Severn wrote the following:

Torlonia, the banker, has refused us any more money; the bill is returned unaccepted, and to-morrow I must pay my last crown for this cursed lodging place: and what is more, if he dies, all the beds and furniture will be burnt and the walls scraped and they will come on me for a hundred pounds or more! But above all, this noble fellow lying on the bed and without the common spiritual comforts that many a rogue and fool has in his last moments! If I do break down it will be under this; but I pray that some angel of goodness may yet lead him through this dark wilderness. If I could leave Keats for a time I could soon raise money by my painting, but he will not let me out of his sight, he will not bear the face of a stranger. I would rather cut my tongue out than tell him I must get the money—that would kill him at a word. You see my hopes of being kept by the Royal Academy will be cut off, unless I send a picture by the spring…Dr Clark is still the same, though he knows about the bill: he is afraid the next change will be to diarrhoea. Keats sees all this—his knowledge of anatomy makes every change tenfold worse: every way he is unfortunate, yet every one offers me assistance on his account. He cannot read any letters, he has made me put them by him unopened. They tear him to pieces—he dare not look on the outside of any more: make this known.

Six weeks later, Keats was dead.

Feb. 27th.—He is gone; he died with the most perfect ease—he seemed to go to sleep. On the twenty-third, about four, the approaches of death came on. ‘Severn—I—lift me up—I am dying—I shall die easy—don’t be frightened—be firm, and thank God it has come.’ I lifted him up in my arms. The phlegm seemed boiling in his throat, and increased until eleven, when he gradually sunk into death—so quiet that I still thought he slept. I cannot say now, I am broken down by four nights’ watching, no sleep since, and my poor Keats gone. Three days since, the body was opened: the lungs were completely gone. The doctors could not imagine by what means he had lived these two months. I followed his dear body to the grave on Monday, with many English. They take such care of me here—that I must else have gone into a fever. I am better now—but still quite disabled. The police have been. The furniture, the walls, the floor, must all be destroyed and changed. […] The letters I put into the coffin with my own hand.

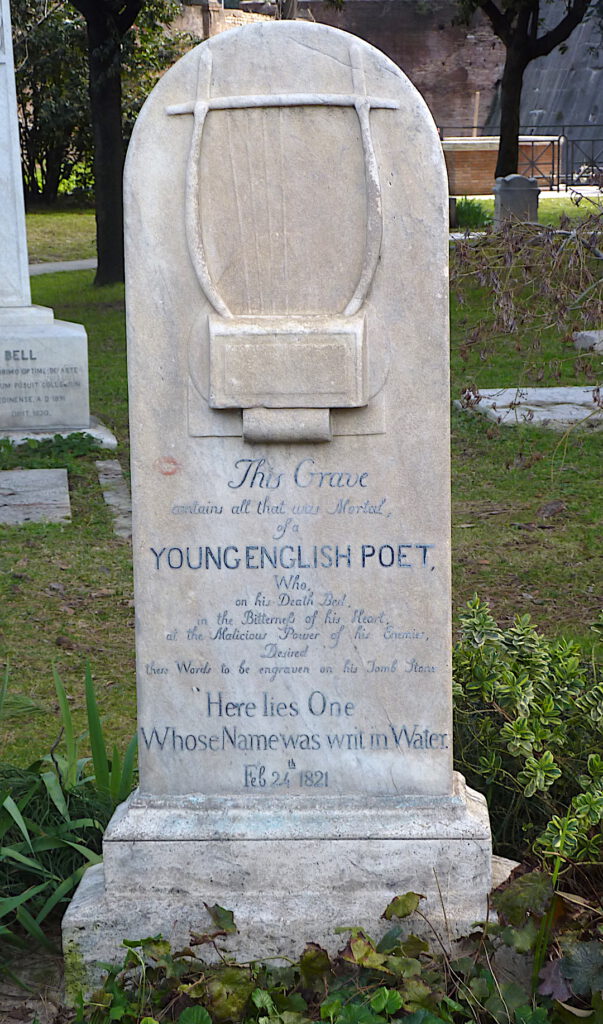

Lord Houghton writes as follows: “Keats was buried in the Protestant cemetery at Rome, one of the most beautiful spots on which the eye and heart of man can rest. […] In one of those mental voyages into the past which often precede death, Keats had told Severn that ‘he thought the intensest pleasure he had received in life was in watching the growth of flowers’: and another time, after lying a while still and peaceful, he said, ‘I feel the flowers growing over me.’ And there they do grow, even all the winter long—violets and daisies mingling with the fresh herbage, and, in the words of Shelley, ‘making one in love with death, to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place.’ Ten weeks after the close of his holy work of friendship and charity, Mr Severn wrote to Mr Haslam:—‘Poor Keats has now his wish—his humble wish, he is at peace in the quiet grave. I walked there a few days ago, and found the daisies had grown all over it. It is one of the most lovely retired spots in Rome.’” Forty years later, Severn returned to Rome as British Consul. When he died there, at the age of eighty-five, he was laid to rest by his friend. The two now lie side by side.

An extract from Blue Guide Literary Companion Rome.