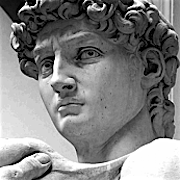

Although Michelangelo’s David is today considered the most important single art object to be seen in Florence (or possibly one of three, along with Botticelli’s Spring and Birth of Venus in the Uffizi), it was largely ignored by visitors up until around 1860, soon after which it was brought inside from Piazza della Signoria to be protected in a specially-built ‘tribune’ in the Galleria dell’Accademia. By 1868 Baedeker had decided it merited a star, and in the 1903 edition of the guide it had become ‘celebrated’.

Today one has the impression that very few tourists are prepared for the many treasures to be seen at the Galleria dell’Accademia, which are of quite another character from Michelangelo’s (now ‘famous’) David. These range from 350 plaster models from the studio of the 19th-century sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini; the collection of musical instruments made by the last Medici and the Lorraine grand dukes, considered one of the most important in Italy (where you can also listen to recordings); Florentine paintings from the time of Giotto up to the 16th century; a large group of paintings by Michelangelo’s close contemporaries; and exquisite individual works such as Giovanni da Milano’s Man of Sorrows (1365). The new director, Cecilie Hollberg, seems to have every intention to steer visitors to all the different parts of the gallery, not just the hall with Michelangelo’s Slaves and St Matthew, and the tribune with his David.

One could almost wish the arrangement of the galleries could be reversed, since at present visitors can be disorientated by the itinerary imposed: you start in the large room of 15th- and early 16th-century paintings with the plaster model made by Giambologna for his Rape of the Sabines in the Loggia della Signoria. Off this is the museum of musical instruments, after which you pass through the gallery with Michelangelo’s great works. From the tribune with the David there are conspicuous signs to the exit which is routed through the gift shop. But you also pass three rooms of the earliest paintings and this is also the way to the stairs (and inconspicuous lift) to the top floor, where there are paintings dating from 1370 to 1430.

Some of the most interesting works it would be a great pity to miss on the race to the David and then out, are described below:

Close together on the entrance wall of the first room are two paintings dated around 1460: the so-called Cassone Adimari (which may have been a bed-head or a wainscot) with brightly coloured, elegant scenes of a wedding pageant by Masaccio’s younger brother, Lo Scheggia; and, in great contrast, a very dark painting of The Thebaids thought to be by Paolo Uccello. Other curious scenes exist of these desert fathers, who lived around Thebes in Egypt, including one in the Uffizi which is attributed in situ to Fra’ Angelico (even though some art historians have suggested it could have been painted in the 18th century). Also hung on this wall are two beautiful Madonnas by Botticelli dating from the following decade.

Among the well-labelled paintings by Michelangelo’s Florentine contemporaries, one of the most curious (it hangs on the end wall to the right of the David) is the crowded Allegory of the Immaculate Conception, the best work of the eccentric painter Carlo Portelli (signed and dated 1566 on the stool on the left). The iconography is unique, with the graceful, naked Eve portrayed prominently below the Madonna (the new ‘Eve’), while Adam is shown still asleep. At the time the nudity of Eve caused a scandal and she was given a fur coat to restore her modesty. This was finally removed in a restoration in 2013.

The Salone is filled with the 19th-century sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini’s models for his works in marble. This huge, well-lit hall was formerly the ward of the hospital of San Matteo (a little painting by Pontormo shows the room at that time). The extraordinary collection of models (often more interesting than the final marble versions) is arranged more or less as it was left in Bartolini’s studio. The works include serried ranks of some 250 busts: a group of them (on the right and left of the entrance) record the English visitors to Florence who asked Bartolini if they could sit for their portraits (many of these are unique, as the whereabouts of the marble versions, which ended up in private collections in Britain are often no longer known). This is not the case with his well-known portraits of Byron and his mistress Teresa Gamba Guiccioli (there are marble versions both in the National Portrait Gallery in London and in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti). The son of a Tuscan blacksmith, Bartolini spent time in Paris where he worked in the atelier of David and met Ingres, who later painted two portraits of the sculptor. By the time of his death in 1850, he had become the best-known sculptor in Italy. There is an excellent website with a database still in progress.

In the three rooms of the earliest paintings is Giovanni da Milano’s moving Man of Sorrows (beneath the window in the room on the left) and works by other followers of Giotto (and even a fresco fragment with a shepherd and goats attributed to the master himself).

The very peaceful upper floor is a place to savour, away from the crowds. There are even comfortable places to sit down (totally absent on the ground floor). The display is excellent and the extraordinary colourful altarpieces, especially those by Lorenzo Monaco and (on the end wall of the main room) a Coronation of the Virgin by the less well-known Rossello di Jacopo Franchi present a magnificent sight. Here too is an extraordinarily beautiful embroidered altar-frontal from Santa Maria Novella, signed and dated 1336 by a certain Jacopo di Cambio, with scenes from the life of the Virgin decorated with numerous birds. There is a small study room on this floor where you can consult catalogues, also online.

The Gallery has space for small exhibitions, always worth seeing, and usually connected to the permanent collection (in 2015 there was an exhibition of all the paintings known by Carlo Portelli).

So far this year there has been no queue to enter the gallery, but when the crowds begin in March you should book online. NB: All other booking websites charge more and should be avoided. You can also book by telephone, T: 055 294883. When in Florence you can also buy your ticket and book a visit directly opposite the entrance to the gallery at the bookshop and café called myaccademia.com for the same price as at the gallery ticket office itself (the other ticket offices in this street charge more).

It is worthwhile remembering that throughout the year the gallery is almost always much less crowded in the late afternoon (and in the height of the season it can sometimes have extended opening hours).

by Alta Macadam, author of Blue Guide Florence.